eBook - ePub

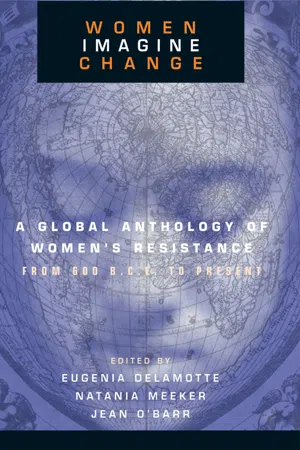

Women Imagine Change

A Global Anthology of Women's Resistance from 600 B.C.E. to Present

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women Imagine Change

A Global Anthology of Women's Resistance from 600 B.C.E. to Present

About this book

This global, multicultural anthology shows how women from some thirty countries, across twenty-six centuries, have found ways to resist oppression and gain power over their lives. Organized around themes of concern to contemporary readers, Women Imagine Change explores: relationships between women's sexuality and spirituality; women's interlinked s

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women Imagine Change by Eugenia DeLamotte C, Natania Meeker, Jean F. O'Barr, Eugenia DeLamotte C,Natania Meeker,Jean F. O'Barr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Vision and Transformation

Eugenia C. DeLamotte

In the preceding section we asked how women learn to resist and transform the particular circumstances of their lives and those of others. We addressed the question: where do women gain the knowledge that inspires and enables them to enact change? This final section views the same question from a wider angle. This time we ask how women have discovered, created, and transmitted the kinds of knowledge that can provide a basis for systemic social transformation. What do women need to know in order to change their world? How can they know it?

One answer that presents itself with increasing urgency is that women must know each other’s lives and experiences. In order to effect meaningful systemic change—change at the level of ideological, political, and economic systems that fundamentally shape women’s lives—women must reach across all kinds of cultural, ethnic, racial, and national barriers. As Gerda Lerner has said, patriarchal systems use “deviant out-groups” construct each other. For that reason, gaining knowledge of each other’s lives means that women must not only learn but unlearn, working to discern ways in which their self-conceptions and conceptions of others may derive from oppressive ideologies. This process of seeing clearly takes place within individual women as well as among them, since all women are taught, in a myriad of ways that reproduce systems of hierarchical dominance, to misapprehend their multiple identities. Such systems teach women—often through the voices and examples of other women—to value or devalue aspects of themselves, to exaggerate some parts as salient, and to ignore others as inconsequent. The first two sets of readings in this section involve these issues of knowing-across-difference, in the context of distinguishing not only the differences among women but also the differences women experience within themselves.

Thinking about such forms of knowledge raises questions about women and the act of knowing more generally. Thus a third group of readings asks, What kinds of knowing do women engage in? What kinds of authority are they able to claim for their knowledge? And what positions do they take toward the established authority of other forms of knowledge, whether embodied in laws or holy texts or social conventions? Such knowledge often assumes the form of so-called definitive information about women; thus a fourth and final group of readings revolves around women’s constructions and reconstructions of knowledge about themselves.

The topic of constructions of knowledge about women leads back around to the topic of women’s efforts to understand each other’s experiences and needs. All four groups of readings reveal that such efforts lead inevitably to an investigation of women’s history. For many of the writers here, that project involves reclaiming stories from the past that can provide an authority for resistance in the present. From Christine de Pizan to Margaret Fell, who use praise for great women of the past as a means of justifying their own speaking positions, to Mọlara Ogundipẹ-Leslie, who looks for indigenous forms of women’s resistance in the history of Africa, to Paula Gunn Allen, who insists that feminists should know who their “mothers” really are, such efforts to know one’s legacy are a constant in women’s studies, and a motivating principle behind our choice of these final selections.

Knowledge Across Difference

The first two groups of selections address the questions of how women come to understand each other across lines of difference, and how they come to understand themselves, individually, across corresponding internal lines of difference. We begin with a group of writers who confront explicitly the problems created when differences disrupt the potential for solidarity. The first of these, Sayyida Salme (Emily Ruete), a woman from nineteenth-century Zanzibar (now Tanzania), deplores false inferences about the supposedly debased status of women in her culture, inferences that appear in Western analyses and arise out of superficial observations made from a far different cultural perspective. The issue she raises was a crucial one in the nineteenth century, when colonizing nations of the West made women and the family a locus for structural transformations of whole societies. Deploring women’s debased status all over the world—except in the West—became a staple of imperial ideology, part of the transmission of a supposedly superior culture to benighted peoples, of whom women were regarded as the most pathetically ignorant and benighted of all.1 Suppositions about women’s inferior status in these cultures, expressed in Western travel literature and Western orientalist theory, worked to mystify the violent economic assault on those cultures—an assault, ironically, of which women tended disproportionately to be the victims. Salme resists the potentially oppressive qualities of her role as an Arabian princess not by glorifying the position of the “European Lady,” but by redefining the notion of “Eastern woman” for a Western audience. At the same time she works to demystify Western notions of the superiority of “Christian wedlock.” Her writing is a reminder of the long history behind contemporary Muslim women’s protests against Western feminists’ misreadings of their lives and needs.2

In contrast to Salme’s complaint, the stories of Kitty Smith, a Native Yukon elder, represent one of the many ways in which women can work cross-culturally to create and preserve information about women’s lives. Through her stories, Smith articulates her knowledge about women in her society, and works with a woman from a different culture to translate this information into a form her grandchildren will be able to read. In this collaboration both parties are aware of the potential dangers arising from ignorance of each other’s culture, and both work to avoid misperceptions in order that succeeding generations can participate knowledgeably in the continuing transformation of a vital cultural heritage.

The excerpts from Anna Julia Cooper, Domitila Barrios de Chungara, and Paula Gunn Allen reveal the importance of women’s knowledge about each other to achieving the solidarity necessary for resistance at the systemic level. Each offers a systemic analysis of women’s oppression; each criticizes a mainstream, predominantly white and middle-class women’s movement for failing to understand what she regards as the crucial issues. In the case of Cooper, a former slave, writing in the late nineteenth century, the starting point is a white feminist’s speech, “Woman vs. the Indian,” which presupposes a competition among oppressed groups instead of seeing that oppressions based on race, class, and gender are all implicated in each other. Cooper sets her criticism of this speech in the context of a larger argument about the kinds of knowledge to which women have special access, a subject that links her writings to those in our third group, as well as to those included here.

For Domitila Barrios de Chungara, the starting point is an international women’s meeting at which, as a Bolivian miner’s wife who has spent years risking her life for social change, she feels herself completely alienated by the dominant conversations. She sees a vast chasm between her and the white bourgeois women she perceives as “fighting [against] men” instead of struggling in solidarity with men for the political and economic changes that will bring about a better life.

Just as Chungara sees almost overwhelming differences between her vision for the future and that of women who, as she says, can afford to wear a different outfit every day, Paula Gunn Allen sees differences between her vision of the past and that of white feminists who are unaware of their “red roots” in Native American women’s history. Clearly, knowing other women’s experience involves learning their past and unlearning distorted versions of it. Allen shows that the Laguna Pueblo question, “Who is Your Mother?” is a crucial question for all feminists, and that the dangers of forgetting what the past can teach us are not merely theoretical but play themselves out in women’s experience: “The root of oppression is loss of memory.”

The selections discussed thus far involve knowledge-across-difference among women. The second group of selections addresses the question of knowledge-across-difference within women. Sui Sin Far, Cherríe Moraga, and Mab Segrest consider the problem of “knowing who you are” within a dominant culture that defines at least some parts of one’s identity as inferior to other parts. Sui Sin Far, a turn-of-the century journalist, searches for knowledge of what it means to be “Chinese” in Canadian and U. S. society. She turns for clues to a family that offers only ambiguous answers and to a culture that teaches lessons of racial inferiority. Her writing provides an extraordinarily subtle account of what it means to learn a multiple identity—to learn who you are within a social construction that presupposes knowledge about you: knowledge to which, initially, you have no access. In particular, she analyzes what it is like to live as a working person in a system of multiple identities.

Cherríe Moraga, in contrast, grew up in a family that did give her directions for interpreting her multiple identities, urging her to claim her status as “la güera,” fair-skinned, and to deny her Mexican heritage. Moraga discusses her struggle to encompass all of her identities in the same circle of meaning, and she links that struggle with struggles for solidarity in the feminist movement. Her focus is on women’s self-knowledge and knowledge of each other; she concludes that the oppressor’s greatest fear is the fear of knowing oneself to be deeply connected with those who seem safely distant as Others. She sees this dynamic at work not only among women, but within women as they confront an internalized oppressor.

Mab Segrest, too, received a great deal of instruction from her family, who gave her the sense that her membership in privileged racial, class, and religious groups made her Somebody: a belief she experienced as dissonant with her sense of belonging to the unprivileged category of lesbian. As she works to unlearn this false knowledge about herself—deconstructing her social construction as white, Christian, a person with Background—she is also exploring the problem of unlearning what she had been taught about other women.

Women and the Sources of Knowing

As women struggle to know each other and themselves across barriers of difference, the question often arises of how we know: is experiential knowledge better than theoretical knowledge? do women know in ways different from (inferior to, superior to) the ways men know? do women have radically different bases for their knowledge? do they theorize in different ways? do certain kinds of privilege (for example, upper-class, white, male, heterosexual) irrevocably preclude certain kinds of knowledge? In one sense, these are epistemological questions—questions not just of how we know, but of how we know that we know. And they are by no means confined to abstract academic discussions. The question of how we know something emerges often concretely and painfully in conversations at the work place, in the classroom, or over family meals. Inevitably it animates the experience of reading and discussing an anthology such as this one.

Two of the selections included here address the question of knowing at this level. Anna Julia Cooper, who calls for women to bring to light the “feminine side to truth,” has already been mentioned; the fact that this call establishes the context for her vision of women’s solidarity across class and racial lines shows that she, at least, did not regard as merely abstract the question of “how women know.” Mọlara Ogundipẹ-Leslie, a contemporary Nigerian feminist, directly addresses the question of women’s knowledge, especially women’s knowledge about women, as a crucial point of debate with male social and political activists who criticize her for being ignorant of what so-called real African women want. These men say Ogundipẹ-Leslie is too educated, too Westernized; ordinary women do not want change. Is this so, she demands? What do research and analysis tell us? As a member of a women’s group devoted to just such research, she can answer that women’s resistance is not exclusively Western but has taken many indigenous forms throughout Africa. Further, she challenges two assumptions: first, the “myth” that there is no “sex” to intellect (women “know” better, she says), and second, the notion that reading the work of a Western male, Karl Marx for example, is admirable, but reading Western feminist literature is not (208). Ogundipẹ-Leslie exemplifies a mode of knowing that draws on multiple sources: experience (what women know about their own ways of knowing); research (the compilation of data); and a careful consideration of such revered sources of knowledge as the Bible and the Koran. How are we to read these texts, she asks? “Should culture be placed in a museum of minds or should we take authority over culture as a product of human intelligence and consciousness to be used to improve our existential conditions?” (224).

The question of what sources women draw on for knowledge, and what authority they invoke for knowing, is at issue as well in the next group of writings, those of Glückel of Hameln, Margaret Fell, and Soma. Glückeľs story represents women’s intuition, a kind of knowledge with which women have often been credited, or discredited, and which they have variously claimed or rejected in their resistance to assumptions that their intelligence was inferior to men’s. She reports her initial distrust of her own intuition of her baby’s needs, followed by her vindication when, contrary to received opinion, her baby did indeed need exactly the food she had craved in pregnancy. In this case, her claim for the superior access of woman’s intuition to truth is a relatively limited act of resistance on the basis of gender. Hers is not a systemic challenge to patriarchy, but a kind of challenge without which such systemic challenges would not be possible. Her claim to intuitive knowledge is an important claim—one many women have made and continue to ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Geographical/Cultural Table of Contents

- Chronological Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors and Note on Text

- Introduction

- Sexuality, Spirituality, and Power

- Work and Education

- Representing Women, Writing the Body Politic

- Identifying Sources of Resistance

- Vision and Transformation

- Subject Index

- Name Index