- 784 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Industrial Mycology

About this book

This single-source reference provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in industrial mycology. The handbook provides a framework of basic methods, tools, and organizational principles for channeling fungal germplasm into the academic, pharmaceutical, and enzyme discovery laboratories, and discusses the complex range of processes involved in the discovery, characterization, and profiling of bioactive fungal metabolites. This authoritative book provides examples of several recently marketed fungal metabolites for clear demonstration and recognizes the impact of fungi on applications in the pharmaceutical, food and beverage, agricultural, and agrochemical industries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Industrial Mycology by Zhiqiang An in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Industrial Mycology: Past, Present, and Future

ARNOLD L.DEMAIN

Charles A.Dana Research Institute (R.I.S.E.), Drew University, Madison, New Jersey, U.S.A.

JAVIER VELASCO and JOSE L.ADRIO

Puleva Biotech, Granada, Spain

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

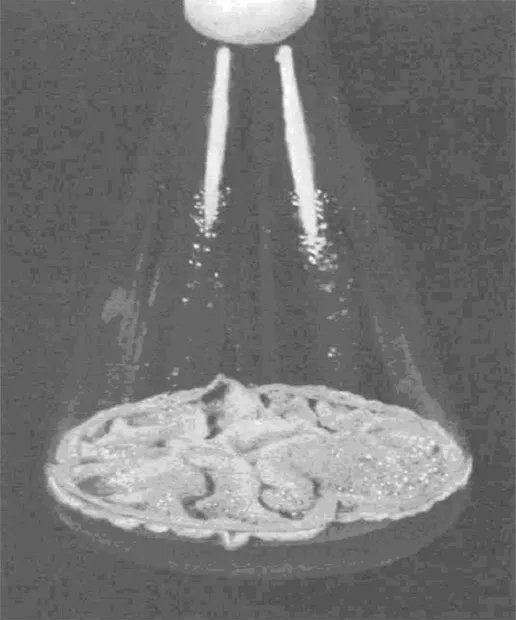

The versatility of fungal biosynthesis is enormous. The use of yeasts dates back to ancient days. Before 7000 B.C., beer was produced in Sumeria. Wine was made in Assyria in 3500 B.C. and ancient Rome had over 250 bakeries which were making leavened bread by 100 B.C. Milk has been made into Kefyr and Koumiss using Kluyveromyces in Asia for many centuries. Today, fungi are producers of five leading fermentation products in terms of tons per year worldwide. These are beer (60 million), wine (30 million), citric acid (900 thousand), single cell protein and fodder yeast (800 thousand), and baker’s yeast (600 thousand). Fungi are also used in many other industrial processes, such as the production of enzymes, vitamins, polysaccharides, polyhydric alcohols, pigments, lipids, and glycolipids. Some of these products are produced commercially while others are potentially valuable in biotechnology. Fungal secondary metabolites are extremely important to our health and nutrition and have tremendous economic impact. The antibiotic market, which includes fungal products (Fig. 1), amounts to almost 30 billion dollars and includes about 160 antibiotics. Other important pharmaceutical secondary metabolites produced by fungi are hypocholesterolemic agents and immunosuppressants, some having markets of over 1 billion dollars per year. In addition to the multiple reaction sequences of fermentations, fungi are extremely useful in carrying out biotransformation processes. These are becoming essential to the fine chemical industry in the production of single-isomer intermediates. The molecular biotechnology industry has made a major impact in the business world, biopharmaceuticals (recombinant protein drugs, vaccines, and monoclonal antibodies) having a market of 15 billion dollars. Recombinant DNA technology, which includes yeasts and other fungi as hosts, has also produced a revolution in agriculture and has markedly increased markets for microbial enzymes. Molecular manipulations have been added to mutational techniques as means of increasing titers and yields of microbial processes and in discovery of new drugs. Today, fungal biology is a major participant in global industry. The best is yet to come as fungi move into the environmental and energy sectors

Figure 1 The mold Penicillium notatum growing in a flask of culture medium for the production of penicillin in the early days of the antibiotic age. (From Ref. 166.)

1.2. Overview

Microorganisms are important to us for many reasons, but the principal one is that they produce things of value to us. These may be very large materials such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrate polymers, or even cells, or they can be smaller molecules, which we usually separate into metabolites essential for vegetative growth and those inessential—that is, primary and secondary metabolites, respectively. The power of the microbial culture in the competitive world of commercial synthesis can be appreciated by the fact that even simple molecules such as lactic acid are made by fermentation rather than by chemical synthesis. Most natural products are made by fermentation technology because they are complex and contain many centers of asymmetry. For the foreseeable future, they probably will not be made commercially by chemical synthesis.

Although microbes are extremely good in presenting us with an amazing array of valuable products, they usually produce them only in amounts that they need for their own benefit; thus, they tend not to overproduce their metabolites. Regulatory mechanisms have evolved in microorganisms that enable a strain to avoid excessive production of its metabolites. Thus, they can compete efficiently with other forms of life and survive in nature. On the other hand, the fermentation microbiologist desires a “wasteful” strain that will overproduce and excrete a particular compound that can be isolated and marketed. During the screening stage, the microbiologist searches for organisms with weak regulatory mechanisms. Once a desired strain is found, a development program is begun to improve titers by modification of culture conditions, mutagenesis, and recombinant DNA technology. The microbiologist is actually modifying the regulatory controls remaining in the original culture so that its “inefficiency” can be further increased and the microorganism will excrete tremendous amounts of these valuable products into the medium. The main reason for the use of microorganisms to produce compounds that can otherwise be isolated from plants and animals or synthesized by chemists is the ease of increasing production by environmental and genetic manipulation. Thousand-fold increases have been recorded for small metabolites.

The importance of the fermentation industry resides in five important characteristics of microorganisms: (1) a high ratio of surface area to volume, which facilitates the rapid uptake of nutrients required to support high rates of metabolism and biosynthesis; (2) a tremendous variety of reactions that microorganisms are capable of carrying out; (3) a facility to adapt to a large array of different environments, allowing a culture to be transplanted from nature to the laboratory flask or the factory fermentor, where it is capable of growing on inexpensive carbon and nitrogen sources and producing valuable compounds; (4) the ease of genetic manipulation, both in vivo and in vitro, to increase productivity, to modify structures and activities, and to make entirely new products; and (5) an ability to make specific enantiomers, usually the active ones, in cases in which normal chemical synthesis yields a mixture of active and inactive enantiomers.

2. PRODUCTION OF FUNGAL PRIMARY METABOLITES

2.1. Alcohols

Ethyl alcohol is a primary metabolite that can be produced by fermentation of a sugar, or a polysaccharide that can be depolymerized to a fermentable sugar. Yeasts are preferred for these fermentations, but the species used depends on the substrate employed. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is employed for the fermentation of hexoses, whereas Kluyveromyces fragilis or Candida sp. may be utilized if lactose or pentoses, respectively, are the substrates. Under optimum conditions, approximately 10% to 12% ethanol by volume is obtained within 5 days. Such a high concentration slows growth and the fermentation ceases. With special yeasts, the fermentation can be continued to alcohol concentrations of 20% by volume. However, these concentrations are attained only after months or years of fermentation. Ethanol is mainly manufactured by fermentation at a level of 4 million tons per year. Because of the elimination of lead from gasoline in the United States, ethanol is being substituted as a blend to raise gasoline’s octane rating. Production of ethanol from starchy crops (mainly corn) reached 1.6 billion gallons in the United States in 2000 [1], whereas in Brazil ethanol produced from cane sugar amounted to 12.5 billion L/yr being used either as a 22% blend or as a pure fuel [2].

With regard to beverage ethanol, some 60 million tons of beer and 30 million tons of wine are produced each year. The fungi used for alcoholic products are wine yeasts (including special flocculent strains for the production of champagne and film-forming strains for the production of flor sherry), sake yeast, top- and bottom-fermenting brewing strains (varying in the degree of flocculation occurring during fermentation), and distiller’s strains for alcohol production from cereal starch. Strain improvement by genetic manipulation and protoplast fusion has contributed superior strains for the above processes. About 2 million tons of yeast are produced for the distilling, brewing, and baking industries each year.

Production of glycerol is usually done by chemical synthesis from petroleum feedstocks, but good fermentation processes are available [3]. Osmotolerant yeast strains (Candida glycerinogenes) can produce up to 137 g glycerol of per liter with a yield of 65% based on consumed glucose and a productivity of 32 g/L/day [4]. In China, 10,000 tons per year are made by fermentation, which amounts to 12% of the country’s need.

Osmotic pressure increase was found to raise volumetric and specific production of the noncariogenic, noncaloric, and diabetic-safe sweetener erythritol but to decrease growth [5]. Production by a Candida magnoliae osmophilic mutant yielded 187 g/L, a rate of 2.8 g/L/hr and 41% conversion from glucose [6]. Previous processes were done with Aureobasidium sp. (48% yield) and the osmophile Trichosporon sp. (1.86 g/L/hr and 45% conversion). Erythritol can also be produced from sucrose by Torula sp. at 200 g/L after 120 hours, with a yield of 50% and a productivity of 1.67 g/L/hr [7].

2.2. Organic Acids

The market for citric acid amounts to $1.4 billion per year, with a production level of 1.6 billion pounds [8]. Citric acid is easily assimilated, is palatable, and has low toxicity. Consequently, it is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industry. It is employed as an acidifying and flavor-enhancing agent, an antioxidant for inhibiting rancidity in fats and oils, a buffer in jams and jellies, and a stabilizer in a variety of foods. The pharmaceutical industry uses approximately 16% of the available supply of citric acid.

Aspergillus niger has an inherent capacity to excrete organic acids during aerobic growth. In 4 to 5 days, the major portion (80%) of the sugar is converted to citric acid, titers reaching about 100 g/L. Another factor contributing to high citric acid production is the low pH optimum (1.7–2.0). Mutants of A. niger resistant to low pH (<2) are improved citric acid producers [9]. Another selective tool is resistance to high concentrations of citrate and sugar [10, 11]. Citric acid exerts negative feedback regulation on its own biosynthesis in A. niger at concentrations above 10 g/L.

Other valuable organic acids include acetic, lactic, malic, gluconic, fumaric, itaconic, tartari...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Mycology Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1: Industrial Mycology: Past, Present, and Future

- 2: Phylogeny of the Fungal Kingdom and Fungal-like Eukaryotes

- 3: Biological Activities of Fungal Metabolites

- 4: Cell Cycle Regulation in Morphogenesis and Development of Fungi

- 5: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of Filamentous Fungi

- 6: Fungal Germplasm for Drug Discovery and Industrial Applications

- 7: Expression of Cosmid-Size DNA of Slow-Growing Fungi in Aspergillus Nidulans for Secondary Metabolite Screening

- 8: The Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Fungal Metabolites

- 9: PCR-Based Data and Secondary Metabolites as Chemotaxonomic Markers in High-Throughput Screening for Bioactive Compounds from Fungi*

- 10: Screening for Biological Activity in Fungal Extracts

- 11: Sordarins: Inhibitors of Fungal Elongation Factor-2

- 12: Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- 13: Genomics and Gene Regulation of the Aflatoxin Biosynthetic Pathway

- 14: Indole-Diterpene Biosynthesis in Ascomycetous Fungi

- 15: Loline and Ergot Alkaloids in Grass Endophytes

- 16: Biosynthesis of N-Methylated Peptides in Fungi

- 17: Molecular Genetics of Lovastatin and Compactin Biosynthesis

- 18: The Aspergillus Nidulans Polyketide Synthase WA

- 19: Pneumocandin B0 Production by Fermentation of the Fungus Glarea lozoyensis: Physiological and Engineering Factors Affecting liter and Structural Analogue Formation

- 20: Strain Improvement for the Production of Fungal Secondary Metabolites

- 21: Fungal Bioconversions: Applications to the Manufacture of Pharmaceuticals

- 22: Metabolomics

- 23: Metabolic Engineering of Fungal Secondary Metabolite Pathways

- 24: Heterologous Protein Expression in Yeasts and Filamentous Fungi

- 25: Toxigenic Fungi and Mycotoxins

- 26: Fungal Secondary Metabolites in Biological Control of Crop Pests