- 808 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Immunoendocrinology in Health and Disease

About this book

One of the first comprehensive references dealing specifically with this new field of interdisciplinary research in medicine, Immunoendocrinology in Health and Disease offers a full scientific picture of where the immune and neuroendocrine systems intersect-placing current understanding of system components, mechanisms, and functions side by side w

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immunoendocrinology in Health and Disease by Vincent Geenen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Endocrinology & Metabolism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Endocrinology & Metabolism1

A Global View of Immunological Development and Biology

RACHEL ALLEN and ANNE COOKE

Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

An effective immune response coordinates the action of organs, circulating cells, and soluble components as an integrated system to eradicate foreign material encountered within the body. Many of these agents are already present within the circulation, under tight regulation yet able to migrate to the source of infection to mount a rapid response upon challenge. Others are stationed within lymphoid organs, awaiting stimulation to direct a targeted immune response. This chapter aims to provide a general overview of how our immune system develops, encompassing innate and adaptive (or acquired) aspects of immunity, their complex interactions, and the regulatory mechanisms that control their actions.

I. KEY PLAYERS OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

A defining characteristic of vertebrate immune systems is the production of a pathogenspecific response that can be swiftly recalled with an increased potency upon repeated challenge. By directing these specificity and memory functions, B and T lymphocytes compose the main cellular agents of the adaptive immune response.

A. Key Cell Types

1. T Lymphocytes

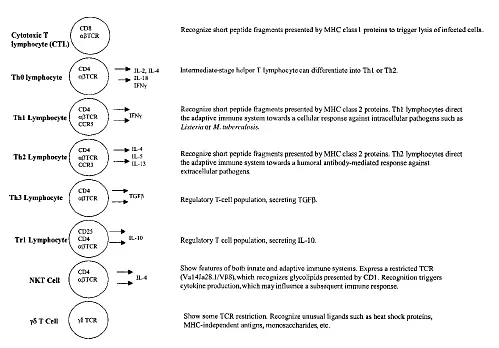

T lymphocytes provide adaptive immunity at a cellular level. The antigen-specific T-cell receptor (TCR) recognizes short peptide fragments displayed on the surface of potential target cells by specialized antigen presenting protein complexes (see Sec. I.C). Distinct populations of T lymphocytes are responsible for various effector functions (Fig. 1). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) (also known as CD8+ T cells due to their characteristic expression of the CD8 co-receptor) are responsible for the lysis of infected or transformed cells. To enable their lytic role, the cytoplasm of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte contains enzyme-rich granules, whose components are released to form pores in the target cell membrane and trigger programmed cell death (apoptosis). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes can also induce lysis through activation of death receptors such as Fas or TNFR on their target cell surface. The primary functions of helper T (TH) lymphocytes (also known as CD4 T cells) are mediated through the action of secreted agents known as cytokines and surface molecules such as CD40L. The TH cell population may be further divided into THO, TH1, TH2, TH3, or Tr1 subsets on the basis of their cytokine secretion profiles. Cytokines produced by TH cells provide stimuli that are essential to support cytotoxic T-cell responses, delayed hypersensitivity reactions, B-cell responses, and monocyte activity. Recent years have seen a growing interest in some unusual T-cell populations that express an invariant set of T-cell receptors, recognize nonpeptide antigens, and/or display a limited tissue distribution. The earliest of these to be identified were T-cell subsets expressing a γδ TCR. More recently, NKT cells expressing a restricted αβ TCR have been shown to recognize glycolipid antigens presented by the MHC-like protein CD1.

2. B Lymphocytes

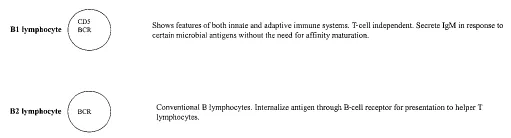

B lymphocytes are the source of antibodies (or immunoglobulins), the soluble effectors of acquired immunity (Fig. 2). Antigen specificity is conferred by the B-cell receptor (BCR), a membrane-bound immunoglobulin that recognizes soluble antigens or extracellular pathogens encountered in body fluids. Upon activation, B cells differentiate to become plasma cells, with the majority of their cytoplasm taken up by protein expression machinery in order to produce secreted antibodies. Antibodies are capable of performing a range of effector functions designed to inactivate or remove foreign antigens from the body (see Sec. I.B). Another key function of B lymphocytes is an ability to present their cognate antigen to T lymphocytes; upon engagement, B-cell receptors internalize their antigen ligand for processing and presentation to T cells. TH cells can then in turn supply the cytokine stimuli necessary to drive B-cell differentiation. Some antigens, however, do not require TH-secreted cytokines to stimulate an effective B-cell response. These Tcell– independent (TI) responses, triggered by antigens with multiple repeating haptens (microbial polysaccharides, for example), can generate IgM antibody without affinity maturation to allow a rapid response in the early stages of infection. TI antigens are generally responsible for activation of the B1 lymphocyte subset, which are characterized by expression of the CD5 marker on their surface. Expression of the pattern recognizing Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on B cells provides another avenue of activation. Naıv̈e B cells only proliferate and differentiate into Ig-secreting cells in response to the TLR9 binding antigen CpG if they are also triggered through the BCR. Memory B cells, however, can proliferate and differentiate in response to CpG directly.

Figure 1 T-lymphocyte subsets.

Figure 2 B-lymphocyte subsets.

3. Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes

Other immune cells support the function of antigen-specific lymphocytes, while performing essential mechanisms of their own. Infectious agents can be eliminated in a variety of ways; alternative means of pathogen destruction are suited to different types of challenge and different phases of the immune response. Phagocytes have developed specialized functions to destroy ingested material and secrete inflammatory mediators that recruit and direct the action of other immune cells. Phagocytosis therefore provides an important frontline of innate immune defense. Although capable of phagocytosis, the primary functions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes are generally secretory. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes can be identified as neutrophils, eosinophils, or basophils on their basis of their dyestaining tendencies. Representing 50–70% of circulating leukocytes, neutrophils are the dominant polymorphonuclear population and are recruited to sites of infection or injury where they play a central role in the inflammatory process. Bacteria ingested by neutrophils succumb to a range of bactericidal proteins stored within cytoplasmic granules. Neutrophils also produce reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) in a respiratory burst following phagocytosis. In contrast, eosinophils are involved in the elimination of parasitic infection, but are also associated with allergic reactions. Eosinophils comprise roughly 5% of circulating leukocytes and are characterized by their acidophilic granules. Upon stimulation, eosinophils degranulate, releasing the contents of their acidic granules into the extracellular environment to combat pathogens that are too large to be phagocytosed. Basophils and related mast cells represent only a small population of circulating leukocytes; their granules contain histamine, heparin, and other vasoactive amines that are released in response to antibody-antigen interactions. The influence of these secreted agents on vasodilation and vascular permeability enhances an inflammatory response. This same process also mediates the symptoms of allergy when basophils and mast cells release histamine in response to IgE sensitization.

4. Monocytes/Macrophages

Monocytes circulate through the blood, undergoing differentiation to become macrophages upon migration into tissues. Tissue-specific macrophages include microglial cells, which become activated in response to pathological events, providing the central nervous system (CNS) with an immune defense system [1]. Specialized receptors on the monocyte/macrophage surface recognize microbial components (see Sec. IV) or agents of the immune response (see Sec. I.B) as signals for phagocytosis. Macrophages/monocytes not only function in pathogen clearance, but also play a pivotal role in the adaptive immune response through their action as professional antigen-presenting cells (APC). High-level expression of MHC class 1I allows professional antigen presenting cells to become potent stimulators of T lymphocytes and thus elicit an adaptive immune response. During an inflammatory response, macrophages can become activated to enhance their phagocytic and secretory functions.

5. Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) form the most potent population of antigen-presenting cells. Dendritic cells are found in every tissue. Immature dendritic cells patrolling the periphery ingest fluid by macropinocytosis and are actively phagocytic, allowing them to acquire potential antigens. Following antigen uptake, the dendritic cell loses its ability to acquire antigen and differentiates into a professional antigen-presenting cell, upregulating the production of MHC class 1I proteins in order to display newly acquired peptide antigens on the cell surface. Subsequent peptide/MHC complexes display a longer half-life and do not recirculate from the cell membrane. Dendritic cells returning through the lymphatic system carry their antigens to lymph nodes, where they deliver an activation signal to stimulate resting T-cell differentiation, thus triggering an adaptive immune response.

6. Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are large, granular lymphocytes with cytotoxic activity and can destroy tumor or virally infected cells with no requirement for prior immunization or activation. NK cells display many features in common with cytotoxic T cells, carrying lytic granules within their cytoplasm and expressing certain protein markers on their surface. Although these leukocytes were first identified and named for their cytolytic properties, NK cells provide two other important functions; they can lyse IgG-coated targets in a process known as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or secrete cytokines that influence lymphocyte function. NK cells appear to play a role in the early phase of the immune response to various intracellular pathogens [2]. Cytokine stimulation can enhance the activity of natural killer cells by up to 100-fold.

B. Soluble Factors

1. Antibodies

Antibodies provide specific immunity in a soluble form. A complex of four protein chains (two heavy and two light) held together by disulfide bonds form the basic structural unit of an antibody (or immunoglobulin). Antibodies are functionally subgrouped on the basis of their heavy chain determinants (known as isotypes); humans have five classes of heavy chains, each designed to evoke a different set of effector mechanisms (Table 1). Each Blymphocyte clone can express only a single specificity of immunoglobulin (see Sec. I.C). However, a B-cell clone can switch heavy chain isotypes during the course of an immune response in order to associate an immunoglobulin specific for a single antigen with a series of heavy chains.

IgM is the first immunoglobulin to be produced during B-cell differentiation, and its membrane-bound form functions as the B-cell receptor (BCR). Soluble IgM molecules form pentamers in serum. IgD can also be found as a membrane-bound BCR, which may be involved in B-cell activation. IgG is the most abundant immunoglobulin in serum and represents the only antibody isotype that can cross the placenta from mother to child. Soluble IgA, found in the form of monomers and dimers, can cross epithelial membranes to become the dominant antibody isotype in secretions. Secretory IgA, found in saliva and milk, associates with the secretory component (a 70 kDa protein synthesized by epithelial cells) to facilitate IgA transport across epithelia [3]. IgE attaches to the surface of basophils and mast cells, ready to trigger their rapid degranulation upon contact with antigen.

Immunoglobulins mediate a number of immune mechanisms. At the simplest level, antibodies may neutralize a pathogenic agent by binding to its surface to block interaction with host cells. Target cell lysis can occur when antibodies on the surface of a pathogen activate complement or are recognized by Fc receptors on the surface of immune leukocytes to elicit antibody-dependendent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (see Sec. IV). Fc receptors specific for different heavy-chain isotypes determine the fine specificity of these processes.

Table 1 Antibody Isotypes

2. Cytokines

Like hormones, this diverse family of soluble mediators may act locally upon the cell of their origin (autocrine), on nearby cells (paracrine), or exert long-range effects (endocrine). Because of their potential for wide-ranging immune modulation, the expression of cytokines and their receptors must be kept under tight regulation. For example, interleukin 1 (IL-1) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine which, due to its effects on a wide variety of cells, must be tightly regulated in vivo. Antagonists that block the interaction between IL-1 and its receptor provide a potential treatment for certain inflammatory conditions [4].

The pleiotropic effects of cytokines acting alone or in concert on a variety of cell types can make it difficult to determine the complex functions of any individual cytokine. However, knockout mice and immunodeficient patients lacking a particular cytokine or its receptor have provided some clues to the primary roles of certain molecules. One of the best characterized examples is provided by patients with inherited disorders of IFN- , who are particularly vulnerable to intracellular infections from viruses and mycobacteria. IL-12 plays an important role in the development of TH1 responses. Thus, patients lacking a function IL-12 receptor are susceptible to intracellular bacterial infections such as Salmonella and mycobacteria [5].

Cytokines have been subgrouped into families on the basis of their source, their range of influence, or structural similarities. For example, hematopoietins such as GMCSF exert their influence upon cells of haemopoetic lineage, while interferons were originally named for their role in antiviral defence. Structural similarities are evident between members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family, which exist as homotrimers and trigger a similar multimerization of their receptors upon engagement. The classic example of a T-cell–derived cytokine or interleukin is IL-2, a small soluble mediator expressed by T lymphocytes as a means to stimulate T-cell activation, proliferation, and further cytokine production. CD4+ T cells in particular express characteristic cytokine profiles which establish their helper functions (Table 2); cytokines that favor a cellular (cytotoxic) immune response to intracellular infections such a leishmania or m. leprae are classified as TH1, and include IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF, and GM-CSF. TH2 cytokines direct a humoral (antibody) response against extracellular pathogens and include IL-4 and IL-10, which stimulate B cells and macrophages, respectively. Antigen-specific T cells are themselves subject to counterregulation by cytokines from other key sources such as regulatory T cells (see Sec. IV), macrophages, and natural killer cells.

3. Chemokines

Chemotactic cytokines or chemokines are intimately involved in the migration of leukocytes through the periphery and their homing to specific tissues. Chemokines are characterized by the presence of a conserved motif of cysteine residues (C). The pattern of these cysteines defines four distinct chemokine families; C, CC, CXC, and CX3C, terminology for chemokine receptors reflects that of their ligands (i.e., CR, CCR, CXCR, CX3CR). Chemokines generated by inflamed tissue recruit circulating immune cells by initiating leukocyte migration across the endothelium. T cell homing can also be determined by chemokine receptor profiles; this can be seen in lymphoid organs, while in the periphery TH1 cells expressing CXCR3 and CCR5 and TH2 cells expressing CCR3, CCR4 and CCR8 localize to different areas of inflammation. Secondary production of further chemokines can then recruit other leukocytes.

Table 2 Cytokines

4. Complement Proteins

The complement system of proteins is involved in inflammation, opsonization of antibodycoated antigens for phagocytosis, lysis of pathogens or infected cells, and immune complex solubilization. These soluble acute phase proteins circulate within plasma as inactive proenzymes. Activation of the complement system triggers a cascade of proteolytic actions whereby proenzymes are cleaved into multiple fragments, which in turn act as soluble immune mediators. Nomenclature for the complement system of proteins can be complex. Factors of the classical complement system are designated by numbers (e.g., C1, C2, C4, C5). Following proteolytic cleavage, lowercase letters are used to designate the multiple fragments (e.g., C5a, C5b), while an overbar indicates an enzymatically active factor. Many components of the alternative pathway are designated by letters (e.g., factor B, factor D).

Complement proteins can follow three main pathways of activation: classical, altern...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1: A Global View of Immunological Development and Biology

- 2: Common Signaling in the Neuroendocrine and Immune Systems

- 3: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Effects on Innate and Adaptive Immunity

- 4: Glucocorticoids and the Immune System

- 5: Cytokines and Leptin as Mediators of the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

- 6: Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Regulating the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis of the Male Rat

- 7: Sex Hormones and B Cells

- 8: Vitamin D3 in Control of Immune Response

- 9: The Growth Hormone/Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Axis and the Immune System

- 10: Somatostatin Control of Immune Functions

- 11: Prolactin and the Immune System

- 12: VIP and PACAP Immune Mediators Involved in Homeostasis and Disease

- 13: Neurotransmitters Talk to T Cells in a Direct, Powerful, and Contextual Manner Affecting Key Immune Functions

- 14: Role of Neuropeptides in T-Cell Differentiation

- 15: Natriuretic Peptides and Inflammation

- 16: Neuroendocrinology of the Thymus

- 17: The Central Role of the Thymus in the Development of Self-Tolerance and Autoimmunity in the Neuroendocrine System

- 18: Two-Way Communication Between Mast Cells and the Nervous System

- 19: Peripheral Nervous System Programming of Dendritic Cell Function

- 20: Neuroendocrine Host Factors in Susceptibility and Resistance to Autoimmune/Inflammatory Disease

- 21: Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes

- 22: Autoimmune Central Diabetes Insipidus

- 23: Autoimmune Thyroid Disease

- 24: Addison’s Disease and Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndromes

- 25: Premature Ovarian Failure

- 26: Myasthenia Gravis

- 27: Rheumatoid Arthritis

- 28: Aging and Neuroimmunoendocrinology

- 29: Quality of Life in Asthma and Rhinitis

- 30: Atopic Dermatitis

- 31: Neuroendocrine Control of Th1 and Th2 Responses: Clinical Implications

- 32: HIV Infection and the Central Nervous System

- 33: Opioid Receptors and HIV Infection

- 34: Mechanisms of Cytokine-Induced Sickness Behavior

- 35: Immunotherapy of Neuroendocrine Tumors

- 36: Glucocorticoid Resistance in Inflammatory Diseases

- About the Editors