eBook - ePub

Increasing the Impact of Your Research

A Practical Guide to Sharing Your Findings and Widening Your Reach

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Increasing the Impact of Your Research

A Practical Guide to Sharing Your Findings and Widening Your Reach

About this book

This important resource helps researchers in all disciplines share their findings, knowledge, and ideas effectively and beyond their own field. By pursuing the practical recommendations in this book, researchers can increase the exposure of their ideas, connect with wider audiences in powerful ways, and ensure their work has a true impact.

The book covers the most effective ways to share research, such as:

- Social media—leveraging time-saving tools and maximizing exposure and branding.

- Media—landing interviews and contributing to public dialogue.

- Writing—landing book deals and succeeding in key writing opportunities.

- Speaking—giving TED Talks, delivering conference keynote presentations, and appearing on broadcasts like NPR.

- Connecting—networking, influencing policy, and joining advisory boards.

- Honors—winning awards and recognition to expand your platform.

Rich in tips, strategies, and guidelines, this book also includes clever "fast tracks" and downloadable eResources that provide links, leads, and templates to help secure radio broadcasts, podcasts, publications, conferences, awards, and other opportunities.

The eResources can be found under the Support Materials heading below!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Increasing the Impact of Your Research by Jenny Grant Rankin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Preparing

Chapter 1

Evolution of the Researcher for Modern Times

Climate change is threatening wildlife. Bigotry plagues society. Guns are killing children on school campuses. Cancer refuses to go away.

Whatever topic you study, there is a problem your findings could help solve. Even if you study inchworms and your focus feels inconsequential to the world’s ills, your findings can advance understanding, spark ideas, and inspire future endeavors.

But no matter your discovery, it cannot help on a widespread scale if you are the only one who knows about it. And sharing your research can be harder than you think.

In fact, sharing your knowledge effectively can be downright counterintuitive. Consider that first example—climate change.

You are aware of climate change, whether you believe it is a problem or not, so we can conclude that scientists have talked extensively about it. But making you aware is not enough. Most researchers’ goal in talking about climate change has been to stop what they have characterized as an unnatural crisis, which requires people to act in specific ways. That is where the communication of findings hit a snag, because people still are not doing enough to stop environmental temperatures from changing.

Researchers have shared all the frightening data: polar bears dying, natural disasters raging, sea levels rising. This is one of the largest science communication failures in history, because catastrophic scenarios are too overwhelming for people to handle (Stoknes, 2015). Grim statistics and forecasts cause people to detach from the issue—a mental state in which they are unlikely to change behavior. Though it is important to share data to provide proof, data shifts people into an analytical frame of mind that works against caring about or acting on the matter at hand.

An attractive story full of meaning, a positive image of a greener future, and fun ways for people to reduce carbon footprints are more effective at prompting people to conserve resources and curtail global warming (Brunhuber, 2016), a major aspect of climate change. For example, Jon Christensen reworked an environmental report that 50 University of California (UC) scientists shared with the United Nations so that it empowered people with easy ways to contribute, such as fun incentives to conserve water. The result was a straightforward, solutions-oriented report that has already changed behavior across 10 UC campuses and beyond.

Sharing findings can be especially hard when people are resistant to a message. Yet understanding our audiences allows us to approach them in ways they will accept. For example, a survey of 10,000 Americans indicated that evangelicals were particularly uninterested in environmental causes; however, 300 interviews revealed that evangelicals merely care more about people. Thus, decrying climate change’s impact on wildlife will leave evangelicals indifferent, but focusing on the human impact (like what happens to children raised amid polluted air and water) holds great potential to move these groups (Ecklund & Scheitle, 2017).

Knowledge of overcoming political stances can also help. When Americans were asked what makes a fact likely to be true, 40% of Republicans versus 72% of Democrats respected the verification of scientists, and 30% of Republicans versus 57% of Democrats respected the verification of academics (AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research & USAFacts Institute, 2019). This indicates a disparity in the weight people of different political persuasions give to researcher input. Returning to our climate-change example, as Democrats and Republicans get better at comprehending science, they actually become more polarized over whether global warming is a valid concern (Kahan et al., 2012). Yet a Yale study revealed that priming people’s scientific curiosity is such a powerful approach to increasing their acceptance of climate findings that it overcomes even political predispositions against such findings (Kahan, Landrum, Carpenter, Helft, & Jamieson, 2017).

The world needs researchers like you to share findings in ways that generate interest and change. Knowing the best ways to do that will maximize your impact. That is where this book comes in.

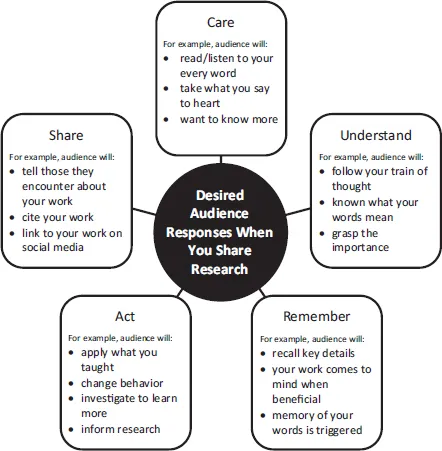

The strategies within these pages will help you reach a larger audience in compelling ways, so people care about, understand, remember, act on, and tell others about your discovery (see Figure 1.0). Pursuing the opportunities in this book can enhance your resume, CV, and career, and likely will increase your professional and personal satisfaction. However, the book’s primary function is to help you increase your discoveries’ benefit to the world, whether that means saving wildlife, advancing society, inspiring a cure for Parkinson’s disease, or helping achieve something else entirely.

Whatever topic you study, you have knowledge that is more valuable when it is shared widely and effectively. Keep reading to enlighten decision-makers, inform communities, improve practices, further research, and widen your impact.

Figure 1.1Desired Audience Responses When You Share Research

“Science and academia in general are not only a source of knowledge but also a guide to how reason can build a better society. Although most researchers do not intend to claim an ethics for humanity, they should nevertheless set an example of behavior for the rest of the population since they symbolize the wisdom of our epoch”

(Corredoira & Villarroel, 2019, p. 1).

Why and How Research Needs to Be Shared

People hold firm opinions on topics without being able to demonstrate knowledge on those topics, and many hold beliefs that do not match academic consensuses. For example, only 37% of U.S. consumers believe genetically modified (GM) food is safe to consume, whereas 88% of scientists believe GM food is safe to consume, and consumers hold these beliefs regardless of whether they have knowledge on the subject (McFadden & Lusk, 2016). There are a number of reasons people outside (and even within) our fields are missing information or are misinformed. Research on behavioral economics reveals that shortcuts (such as biases and heuristics) inherent in people’s decision-making processes lead to faster yet also frequently flawed conclusions (Kahneman, 2011).

Collective opinions, even when misguided, impact how the public thinks and talks about different issues, how the media frames the issues, how politicians make decisions related to the issues, how organizations do or do not fund research on the issues, how academics work on the issues, and more. Yet researchers’ effective and comprehensive communication can enlighten audiences and overturn misconceptions. Going back to the example of GM food, informing consumers resulted in increased acceptance of GM foods, yet only when shared in specific ways, since mere statements from scientists are insubstantial and can even lead to backlash (Lusk, Roosen, & Bieberstein, 2014). Researchers can increase their impact when they share their research well and widen their reach.

This book is based on the premise that researchers should do what is best for the world (humanity, the environment, wildlife—whatever entity one’s research has a chance to help). To further that objective:

- Researchers should share their research extensively.

- Researchers should share their research effectively.

This book helps with these endeavors, but the research community does not always encourage them. That needs to change.

Researchers Should Share Their Research Extensively

When Paul Revere learned British soldiers would march on the towns of Lexington and Concord, he went on a famous midnight ride warning communities. Local militia would have lost the next day’s skirmishes, and possibly the entire American Revolutionary War, if Revere had instead kept his findings to himself. Even if Revere had left his silversmith shop to discuss his findings with those around him, it would not have been enough to save those who Revere had had the potential to help.

Important information needs to be shared with all those who can benefit. Only then can a discovery fulfill its potential for good.

Yet researchers often communicate in silos. This means that they commune with people in the same role (like researcher to researcher), field (like economist to economist), or at the same site (for example, the same university) when sharing knowledge, seeking knowledge, making decisions, and collaborating.

Consider the impact of transcending traditional communication silos. McGrath and Brandon (2016) shared how family-integrated care (FiCare) researchers increased family engagement in Canadian neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). The authors published findings in scholarly journals, but they also enlisted mainstream media, blogs, social networks, a researcher website, project videos, and a variety of conferences and venues. This caused most neonatal care providers to be familiar with the intervention strategy and several more trials were conducted in Canada, the U.S., and abroad.

Sometimes sharing does not even occur regularly and fluidly within silos, and the problem can be long established. Consider knowledge management, which is the process of exchanging and using information to maximize its value. Kidwell, Vander Linde, and Johnson (2000) found that while some examples of sharing knowledge within higher education existed, they were “the exception rather than the rule” (p. 28). When Veer Ramjeawon and Rowley (2017) examined this same issue years later, they found participants knew about knowledge management but more barriers than enablers to knowledge management were identified, and none of the universities had a knowledge management strategy. These same-silo and restricted-sharing paradigms limit awareness of knowledge available.

To meet this challenge, academics need to expand their reach when sharing knowledge. Researchers cannot share their discoveries only with readers of an academic journal, or practitioners too busy to read those journals will make decisions that do not benefit from those discoveries. Fields cannot keep findings to themselves, or cross-field innovations will never benefit society. Professors cannot share their discoveries only with their professor colleagues, or policymakers will make decisions that do not benefit from those discoveries. Additional examples can pair different stakeholders to the same effect.

Transcending the boundaries of traditional silos can occur if scholars make efforts to share their expertise with audiences of all natures, within their own traditional silos and outside their silos. As you share with varied constituents, you can also learn from them, so your research best serv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- eResources

- Acknowledgments

- Meet the Author

- Part I Preparing

- Part II Writing

- Part III Speaking

- Part IV More Options

- Index