- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecology of Communication

About this book

Altheide's new book advances the argument set in motion some years ago with Media Logic and continued in Media Worlds in the Postjournalism Era: that in our age, information technology and the communication enviroments it posits have affected the private and the social spheres of all our power relationships, redefining the ground rules for social life and concepts such as freedom and justice., Articulated through an interactionist and non-deterministic focus, An Ecology of Communication offers a distinctive perspective for understanding the impact of information technology, communication formats, and social activities in the new electronic environment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecology of Communication by David L. Altheide in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Ecology of Communication and the Effective Environment | 1 |

[The owner of the Boston Braves, James Gaffney] wanted a ballpark conducive to inside-the-park home runs, his favorite kind of baseball action, and that’s just what he designed. The new park [Braves Field] was laid out so that the distance from home plate was 402 feet down each foul line and 550 feet to dead center. These wide-open spaces generated plenty of triples and inside-the-park homers, but the corollary was that hardly anyone could muscle the ball out of the park for a real honest-to-goodness Babe Ruth–type home run. …Braves field succeeded admirably in producing inside-the-park homers. In 1921, for example, 34 out of 38 home runs hit there were of the inside-the-park variety. … Responding to fan demand, Braves management joined the parade and in 1928 pulled in the outfield fences by installing new bleachers in left and center fields. These shrank home-run distances to 320 feet down the left-field line, 330 feet to left center, 387 to center, and 364 feet down the right-field line. … [It is noted that many homeruns were hit.] Back to the drawing board. Hard to believe, but starting in 1928 the dimensions of Braves Field were altered almost annually.—Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks:

A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields

INTRODUCTION

Owners of baseball teams changed the playing fields to suit their teams and preferences, and changed the nature of the game. The playing fields of social life have also been altered by changes in information technology. While the fields are a spatial dimension, information technology has altered the temporal order of activities. This book examines how this is happening and what some of the consequences are for life in a postindustrial society.

Changes in communication media have altered social processes, relationships, and activities as information technology expands to mediate more social situations. While it is commonplace among social theorists that the message reflects the process by which it was constituted, they have paid much less attention to how social activities are joined interactively in a communication environment, and particularly how the techniques and technology associated with certain communicative acts contribute to the action. Just as the dimensions of a baseball field contribute to the nature, style, and quality of play, so do the information technologies and organizing formats influence social activities. Seasoned fans are aware of a ballpark’s contributions to a player’s and team’s success; they know that “playing” occurs in an important context, even if the context does not determine the outcomes. They know, for example, that one of the greatest plays of all time, Willie Mays’s “over the shoulder” catch of Vic Wertz’s 445-foot drive, would not be made today since no major league ball park has a field with these dimensions; Wertz’s smash would be merely a home run today. These considerations form part of a fan’s perspective and add immensely to the discourse of baseball, which serves to question and challenge cold “objective” facts, e.g., how many home runs a player hit in a given year or would hit today. One of the aims of this book is to contribute to the scholarly—and then “everyone’s”—discourse about social activities by drawing out some crucial contextual features of contemporary social life. A related aim is to offer a perspective for examining social activities to see the relevance of information technology.

The notion that new media and technology can influence communication (cf. McLuhan 1962) can be contextualized by examining the impact of information technology in symbolic environments. Halloran’s appeal for investigation into a wide range of information technologies is consistent with this book. Part of a comprehensive approach is:

[t]o examine the introduction, application and development of the new electronic and communication technologies, the factors (for instance, finance, control and organization) which influence these processes, and related institutional changes at both national and international levels. (1986:57)

Following the insight by a host of symbolic interactionists that communication occurs in a context, as well as Barnlund’s (1979) suggestion that the matrix of communication systems is most significant for understanding meaning, we examine the connections between some key elements of the social matrix involved in the definition, construction, and use of actionmeaning systems in modern life. This book (1) offers a sensitizing concept (cf. Blumer 1969), ecology of communication, (2) to help grasp how social activities are joined with information technology, (3) to offer a perspective for reconceptualizing how communication frameworks can inform social participation, and (4) how activities can be investigated to clarify the significance of the communicative dimensions.

In its broadest terms, the ecology of communication refers to the structure, organization, and accessibility of information technology, various forums, media, and channels of information. It is incontestable that media and technology can make a difference in social life, although the nature and extent of this difference remains an issue. In order to promote this debate, the chapters that follow provide a conceptualization and perspective that joins information technology and communication (media) formats with the time and place of activities. This study is quite focused and does not address the entire range of questions about the effects of information technology on a global scale, although the pieces discussed in the following chapters would certainly be relevant for such a study. The research focus, then, is on specific activities and events as cases of the ecology of communication. But just as the emphasis is not on all societies, the emphasis is not on individuals (cf. Poster 1990) or on comparative study of diverse societies (cf. Traber 1986). Students of postmodernism and those operating with perspectives ranging from neo-Marxism to poststructuralism to critical theory offer erudite views of the role of communication technologies on subjects or individuals, including, for example, the impact of TV ads on viewers—even though actual viewers are seldom studied (cf. Poster 1990:43)! One of the major differences of our approach is that social interaction and social context are stressed in understanding the social impact of new information technology. Specifically, social meanings are derived through a process of symbolic interaction, even between a TV viewer and a program; mass media interaction is not “monologic” as poststructuralists assert, but involves two-way (dialogic) and even three-way (trialogic) communication. Nevertheless, as we reiterate below, behavior is not totally situational, unique, or random; social actors do have to take into consideration aspects of their effective environment that are not of their own making, including electronic media and information technologies. Accordingly, despite certain important theoretical differences between students of “information culture,” there is a common interest in the way the social context and field of social interaction incorporate communication and information technology. However, the main focus in this work is on select activities and emphases:

[T]hat the configuration of communication in any given society is an analytically autonomous realm of experience, one that is worthy of study in its own right. Furthermore, in the twentieth century the rapid introduction of new communicational modes constitutes a pressing field for theoretical development and empirical investigation. (Poster 1990:8)

While Traber is certainly correct that innovations and changes “need to be examined within the wider social context, and in the light of current social trends” (1986:47), the following chapters focus on the intersection of communication and information technologies and the implications for certain organized and routine activities. With Meyrowitz (1985) and others who have addressed the relevance of information technology and communication formats for social interaction and a “sense of place,” the challenge for this study has been to refine further a perspective for understanding the role of communication in the time, place, and manner of social conduct.

The activities presented in the following chapters are simply those which were theoretically relevant and accessible to obtain the relevant data. They include testing and surveillance (especially this chapter), computer databases and orientation (Chapter 2), public information and self-awareness (Chapter 3), dispute resolution (Chapter 4), informal and formal legal sanctioning (Chapters 5 and 6), claims-making and the construction of a “social problem” (Chapter 7), diplomacy and terrorism (Chapter 8), and modern warfare (Chapter 9).

Several points must be very explicit at the outset:

First, many of the ideas, concepts and metaphors in the following chapters have been developed by others, including McLuhan and Innis, as well as a host of cultural studies scholars like Fiske and Carey. Cogent readers will see the influence of many symbolic interactionists and that tradition (e.g., Couch), as well as ethnomethodology, phenomenology, and existential sociology. While I assume responsibility for errors of omission and commission, there is a sense of “collective guilt” as well.

Second, I am not a technological determinist and do not endorse this perspective; the arguments to follow treat information technology as a component/aspect/feature/contributor/etc. of a changing social environment, increasingly embedded in a context of technological/organizational/control that operates according to communicative guidelines and codes referred to as formats.

Third, this work is part of a two-decade project to explicate how television news, official information, and electronic technology have contributed to the process of defining the situation for people in everyday life and public officials through social interaction and continually emerging social institutions.

Fourth, while many of the examples in the chapters that follow refer to television materials, and particularly news items, the argument extends beyond television and explicit communication media: indeed, the focus in this book is to expand the project beyond the discussions of mass media formats to other elements of an ecology of communication. The emphasis is on the role of information technology in shaping numerous social activities that are not directly related to mass media products.

Fifth, I do not regard all of the changes in activities as bad or undesirable, nor is there an implicit call to arms to ban, halt, legislate, or actively oppose them.

The intent is to clarify how some information technology can combine with organizational logic and frameworks to influence social activities. Another useful metaphor to complement that of the playing field is Lind’s “culture stream”:

What is clearly needed for most societies over long time periods is a model of processes by which the content of the culture pool is itself transformed, such that we must speak of the culture stream. (1988:178)

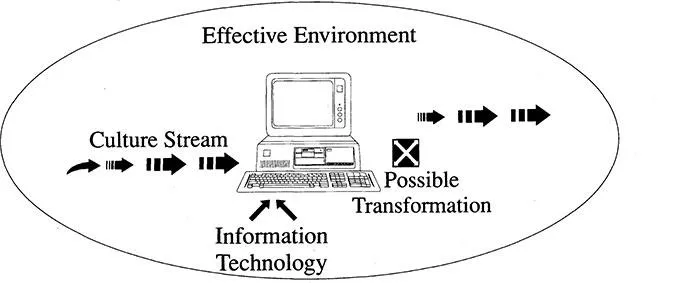

As a student of information technology, Lind explores cultural continuities and change, reflecting on the mechanisms and institutional forms that permit the past to be remembered in the present and passed along and changed in the future. The focus sharpens how cultural processes that are discovered, tested, altered, instituted, and then reified become taken for granted (cf. Berger & Luckmann 1967; Schutz 1967). These social forms join generations, as history runs through the present into the future. As suggested in Figure 1.1, various technologies (cf. Couch 1984) of communication facilitate these transitions and their embeddedness as part of the culture.

As Figure 1.1 indicates, there are numerous possibilities for the direction of change and transformation. It is the transformation dimension that is most relevant to our focus in this work, because as activities either change or emerge due to encounters with human agents sporting certain technologies and techniques, then old activities are transformed into new, but familiar ones, which in turn come to be taken for granted:

This transmission system takes on new significance, however, as we see information which has been inserted into ordinary members of the society by specialist disseminators beginning to be transmitted via the mechanisms of the informal culture stream, i.e., via adult-child relations, friendship, and other nonspecialist modes of contact. The loops of the face-to-face transmission system grow in complexity as more and more material from the formal system is internalized and passed on informally. (Lind 1988:181)

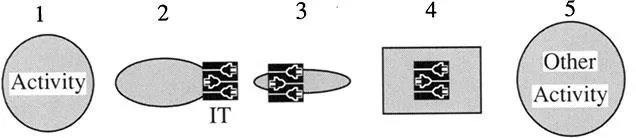

The process is how something new and different becomes internalized and eventually assumed and taught as something everyone knows. One’s effective environment is contextualized by the culture stream and this encompasses the ecology of communication. When numerous activities are engaged in by human actors, and when these activities incorporate information technology and communication formats, then effective environments essentially become similar. One model is offered in Figure 1.2:

The models developed here require reference to temporality: (1) the model of transformation requires a T1 and a T2, and (2) what is characterized here as the “culture stream” consists of cultural information transformed in an ongoing way over time. Cultural innovators are working on old elements already in the culture stream, metamorphosing them into new meanings—i.e., simultaneously effecting an input (new variant) and an old output (old variant). (Lind 1988:188)

It is the relevance of the effective environment and information technology to the culture stream that challenges the researcher. The use of case studies and constant comparative method of certain activities and events is a useful approach to articulate this interaction. One of Carey’s provocative studies of the role of the telegraph in social life illustrates the relationship:

I tried to show how that technology—the major invention of the mid–nineteenth century—was the driving force behind the creation of a mass press. I also tried to show how the telegraph produced a new series of social interactions, a new conceptual system, new forms of language, and a new structure of social relations. In brief, the telegraph extended the spatial boundaries of communication and opened the future as a zone of interaction. It also gave rise to a new conception of time as it created a futures market in agricultural commodities and permitted the development of standard time. It also eliminated a number of forms of journalism—for example, the hoax and tall tale—and brought other forms of writing into existence. … Finally, the telegraph brought a national, commercial middle class into existence by breaking up the pattern of city-state capitalism that dominated the first half of the nineteenth century. (1989:70)

Carey is not arguing that the telegraph caused these changes, but that many activities and approaches emerged as new applications for this technology were discovered. Similarly, what follows below should not be read as an arg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Title

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Ecology of Communication and the Effective Environment

- 2 Computer Formats and Bureaucratic Structures

- 3 The Culture of Electronic Communication and the Self

- 4 Dispute Transformation and the Ecology of Communication

- 5 Gonzo Justice

- 6 Gonzo Democracy:The Case of Azscam

- 7 Policy and the Ecology of Communication: “The Missing Children Problem”

- 8 The Ecology of Communication and Tv Coverage of Terrorism in the United States and Great Britain

- 9 Postjournalism:The Gulf War in Perspective

- 10 Conclusion: Our Communicative Future

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index