- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exploring the wide array of structures, substances, and environments that are primary factors in the initiation or inhibition of sleep, this reference highlights key findings from respected professionals around the globe on the social and economic burden of impaired performance, productivity, and safety arising from sleep deprivation-studying pharm

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sleep Deprivation by Clete A. Kushida in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pulmonary & Thoracic Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Consequences of Sleep Loss

10

Epidemiological Health Impact

Daniel F. Kripke and Matthew R. Marler

University of California-San Diego, La Jolla, California, U.S.A.

Eugenia E. Calle

American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A.

I. Sleep Duration and Mortality Risk

In 1964, E. Cuyler Hammond presented preliminary findings of the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study I (CPSI), using early follow-ups (1). He noted that men who reported that they slept 7 hr had the lowest mortality in age groups from 45–1-9 to 85+ years. Both those men who reported that they slept 6 hr or less and those who reported that they slept 8 hr or more had higher mortality. Statistical reliability was self-evident from trend consistency among 17 of 18 groups studied. Results with 6-year follow-up of 1 million subjects of both sexes have expanded this result with control for several possibly confounding risk factors (2).

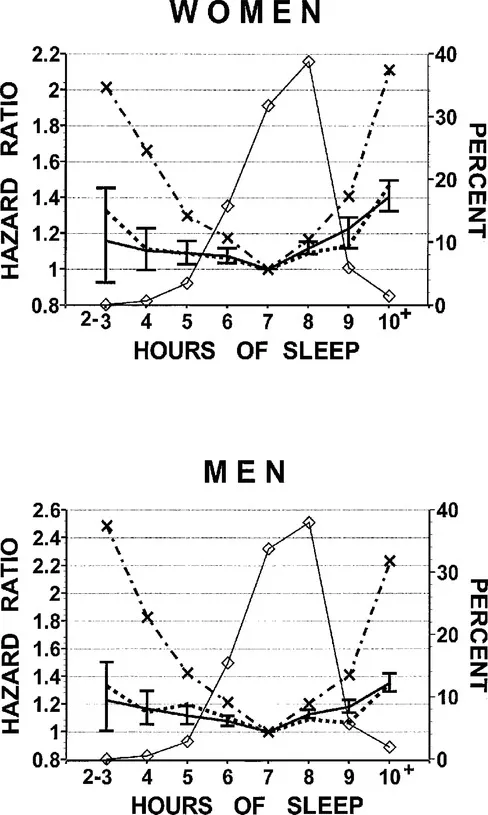

In the Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII), a new prospective sample of 1.1 million participants aged 30–102 years was followed for 6 years (3). Similar to the prior results, reported sleep durations greater or less than 7 hr/night were associated with increased mortality after controlling for 32 risk factors. In CPSII, reported usual sleep of 6.5–7.4 hr had been coded as 7 hr, 7.5–8.4 hr as 8 hr, etc. In both CPSI and CPSII, the minimal mortality risk was found in the group reporting 1 hr less sleep than the mode of 8 hr. In the U-shaped relationship of mortality hazard to reported sleep duration, long sleep was associated with more risk than short sleep. This was both because there were more participants reporting sleep > 7 hr (46.3% women and 45.7% men) than those reporting sleep < 7 hr (20.2% and 19.1%, respectively), and because of a more rapidly increasing hazard curve > 7 hr sleep (3) (Fig. 1).

Additional smaller studies, some of them based on representative population samples, have also observed increased mortality associated with short and long sleep (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and 14). Recent reports have further confirmed the U-shaped pattern with data from the Framingham Study and the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study (15,16). Important features of the Japanese collaborative study were confirmation that the minimum risk is at 7 hr for self-reported sleep duration and a control for depressive symptoms. There has been widespread and convincing replication of the epidemi-ological risks associated with reported short and long sleep. There has been no study that reliably contradicted the general findings of Dr. Hammond, though some studies with insufficient power have failed to replicate his findings.

In this discussion, we will present a reanalysis of the CPSII data, to further explore the influence of comorbid risk factors on the mortality associated with sleep duration. The risks associated with insomnia, shift work, and sleeping pills will also be examined.

A. The Effects of Comorbidities

The question arises whether the association of sleep duration with mortality hazard could be an artifact of comorbidities, since so many diseases, disorders, and discomforts are associated with disturbed sleep. In our prior analysis of CPSII, we controlled as far as possible for the major risk factor data available from the CPSII questionnaires, to see if such extensive control for comorbidities would eliminate the significant associations of mortality hazard with sleep duration.

In Figure 1, the CPSII hazard ratios for sleep duration, derived from Cox proportional hazards survival models, are presented with controls only for gender, age, insomnia, and sleeping pill use. The hazard ratios are also presented (with confidence intervals) for models simultaneously controlling for 32 covari-ates and comorbidities, as described in our previous publication (3). Minor differences between Figure 1 and results previously reported were due to reediting of the data file and inclusion of those reporting 2–3 hr sleep as a single group, since too few reported 2 hr sleep for an accurate estimate. Also plotted are models restricting analysis to participants who were relatively healthy in the initial questionnaires, by considering only deaths taking place at least 1 year after entry into the study (to exclude those moribund at entry), and by eliminating individuals who had reported any cancer, heart disease, hypertension, stroke, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, or current illness (a “yes” answer to the question “are you sick at the present time?”).

In Figure 1, it may be seen that controlling for the multiple comorbidities substantially reduced the hazard ratios related to sleep greater than 7 hr, and even more greatly reduced the hazard ratios associated with sleep less than 7 hr. Evidently, a higher proportion of deaths associated with short sleep could be attributed to comorbidities than deaths associated with long sleep. Further excluding those who died within the first year and excluding those who were not healthy at entry (instead of controlling for the same factors in the 32-covariate Cox proportional hazards models) made no consistent change in the hazard ratios. In summary, we were not able to account for all mortality associated with short and long sleep by controlling for other major risk factors. Association of sleep duration with mortality remained after maximal control for comorbidities.

Figure 1 The relative 6-year mortality hazard ratios are shown for reported usual sleep hr from 2–3 hr/night to 10 or more hr/night, relative to 1.0 assigned to the hazard for 7 hr/night as the reference standard. The solid line with 95% confidence interval bars shows results from a 32-covariate Cox proportional hazards survival model, as reported previously (3). The dotted lines show data from models that excluded subjects who were not initially healthy, i.e., who died within the first year or whose questionnaires reported any cancer, heart disease, stroke, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, or current illness (a “yes” answer to the question “are you sick at the present time?”). The dot-dash lines with X symbols show models controlling only for age, insomnia, and use of sleeping pills. Data were from 635,317 women and 478,619 men. The thin solid lines with diamonds show the percent of subjects with each reported sleep duration (right axis).

B. The Question of Causality

We are not certain which comorbid risk factors cause mortality independent of sleep effects, and therefore, we cannot be certain whether we controlled too much or too little for comorbidities. For example, since short sleep or long sleep may cause a person to be “sick at present” or to get little exercise or to have heart disease (17), diabetes (18), etc., controlling for these possible mediating variables may have incorrectly minimized the hazards associated with sleep durations. This would be overcontrol. The hazard ratios for participants who were rather healthy at the time of the initial questionnaires were unlikely to be overcontrolled for initial illness. Since the 32-covariate models and the hazard ratios for initially healthy participants were similar, this similarity reduced concern that the 32-covariate models were overcontrolled. On the other hand, there may have been residual confounding processes that caused both short or long sleep and early death that we could not adequately control in the CPSII data set, either because available control variables did not adequately measure the confound or because the disease did not yet manifest itself. Depression, sleep apnea, and dysregulation of cytokines are plausible confounders that were not adequately controlled. It may be impossible to be confident that all conceivable confounds are adequately controlled in epidemiological studies of sleep.

The question of causality can only be fully resolved with controlled studies that randomly control sleep duration. For short sleep, controlled trials of long-term prescription of hypnotics or long-term use of sleep hygiene, etc., may help us understand the causal role of sleep. Similarly, for those with long sleep, controlled restriction of sleep or time-in-bed may help clarify the causal pathways.

An inverse correlation of sleep duration with longevity (r = -0.52) was found across 53 mammalian species, albeit these data are open to several interpretations (19). This interspecies comparison supports the hypothesis that long sleep may have an adverse causal effect on mortality, or conversely, that long wake may be life-preserving.

C. Confounding Variables

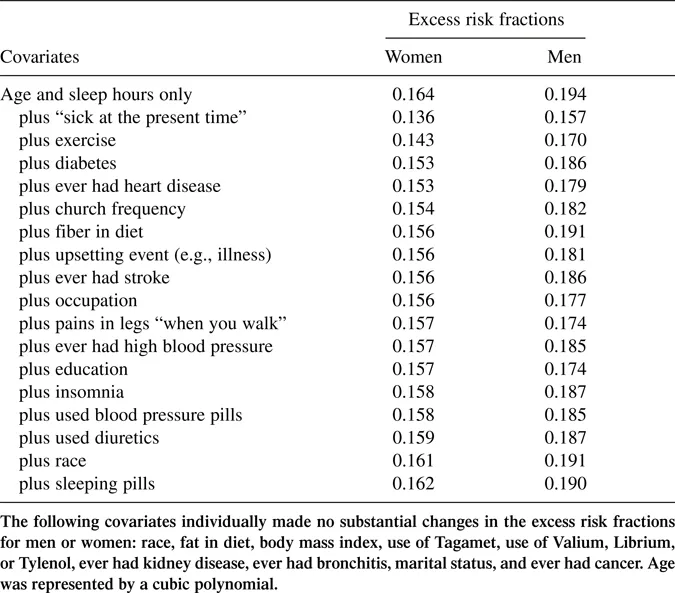

It is interesting to examine how control for various comorbid factors influences the mortality hazard associated with sleep durations. Comorbidities aside, in Cox proportional hazards models for each gender, controlling only for age and hours of sleep, the sample excess fractions (20) of deaths related to sleep durations other than 7 hr were 16.4% for women and 19.4% for men. These fractions are the percentage of observed deaths that would not have occurred in the 6-year follow-up, if those with all sleep durations had the same survival rates as those of the same age who slept 7 hr. In Table 1, we compare the sample excess fractions estimated similarly, controlling for one additional risk factor at a time. Table 1 shows that control for a report of being “sick at the present time” reduced by 3–4% the sample excess fraction related to sleep other than 7 hr. Control for exercise intensity reduced the fraction 2–3%. None of the other risk factors by itself could explain much of the total excess risk fraction for sleep durations. However, as previously reported (3), when all 32 available risk factors were entered into the model, these sample excess fractions of deaths were reduced to 6.3% for women and 5.3% for men. That is, of the mortality hazard associated with not sleeping about 7 hr, 62% of the hazard in women and 73% of the hazard in men could be attributed in the Cox models to a diverse combination of confounding comorbid factors. Although most of the mortality hazard associated with not sleeping 7 hr could be attributed to other factors, the remaining excess fraction was a serious portion of total sample deaths.

Table 1 Excess Risk Fractions Associated with Sleep Hr by Covariates

II. Long Sleep and Morbidity

Many people believe that sleep of 8 hr or more is necessary for optimal function and health, but this is not the case. Our University of California, San Diego group examined health-related quality of well-being in a representative sample of San Diego, from which objective home sleep recordings were obtained (21). There was no correlation of sleep duration with quality of well-being, a global measure of function. In college students, Pilcher and colleagues found that sleep quality (which was associated with psychological symptoms) was much more related to measures of health than was sleep quantity, which was not consistently related to the primary measures of health (22,23). It is interesting to note that cross-sectional and epidemiological studies have found that long sleepers have more psy-chopathology than short sleepers (24,25). In general, long sleepers appear more depressed and less energetic (26). In analysis of three large surveys, our group has found that those reporting longer-than-average sleep report som...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- Preface

- Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Evaluation of Sleep Loss

- Sleep Loss in Disease States

- Special Populations

- Consequences of Sleep Loss

- Short-Term Countermeasures for Sleep Loss Effects

- Critical Theoretical and Practical Issues

- Index