- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Internal Marketing: Directions for Management

About this book

Bringing together contributions from leading writers in the field of service marketing and management, this book represents a much-needed source of current research and conceptual development in internal marketing. Key themes and issues explored include:* the social model of marketing* the human resource management perspective* marketing and servic

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Internal Marketing: Directions for Management by Barbara Lewis,Richard Varey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Context

1 From hierarchy to enterprise

Internal markets are the foundation for a knowledge economy1

Introduction

During the 1990s decade of Capitalism Triumphant, we heard constantly about the evils of central planning and authoritarian control. Yet the prevailing corporate structure remains a centrally-managed hierarchy, albeit adorned with a few gentle touches and good intentions. Despite recent claims about empowerment, teams, networking, and other progressive management concepts, this was also a decade of harsh downsizing, top-down change, and extravagant executive pay. Beneath the rhetoric, little is really different.

The problem is that we need flexible dynamic organizations, but the concepts in currency today simply cannot get us there. We usually have meager measures of performance below the level of major divisions, so it is hard to know if empowered people working in teams actually create value or destroy it; the result is little sound basis for ensuring accountability or allocating resources effectively. Further, without some form of decentralized control, major decisions must still be made by top management, thus reducing operating managers to bureaucrats rather than entrepreneurs. Many advocate just allowing employees the freedom to be more flexible, but unguided freedom soon becomes anarchy.

Other concepts that purport to replace the hierarchy suffer from the same limitation. There is the federal organization, the boundaryless corporation, the learning organization, the agile company, the spider’s web, and so on. These ideas may encourage a more fluid variation of hierarchy, but they do not answer the questions raised above. The issue remains: how can an organization be designed as a true bottom-up system that permits spontaneous creativity while maintaining some form of coherent control?

Fundamentally, this problem will resist solution as long as we continue to think instinctively of management within a hierarchical control framework. Major corporations comprise economic systems that are as large and complex as national economies, yet they are commonly viewed as private firms to be managed by executives: moving resources about like a portfolio of investments, forming global strategies, restructuring the organization, and setting financial targets. How does this differ from the central planning that failed in the Communist bloc? Why would such control be bad for a national economy but good for a corporate economy? Can any fixed structure remain useful for long in a world of constant change?

Top-down management may be working temporarily, but it is not going to withstand the massive changes looming ahead as relentless hypercompetition drives open a frontier of new products, markets, and industries that nobody really understands. A knowledge-based global order is emerging rapidly, yet the bulk of useful knowledge lies unused among employees at the bottom and scattered outside office walls among customers, suppliers, communities, and other stakeholder groups. Andrew Grove, former CEO of Intel, put it best: “The Internet is like a tidal wave, and we are in kayaks” (Grove, 1996).

Downsizing, for instance, seems to make sense from a capital-centred view, but the knowledge held by employees comprises 70 percent of all corporate assets! (Stewart, 1996). To put it more sharply, the economic value of employee knowledge exceeds all of the financial assets, capital investment, patents, and other resources of most companies. Today’s downsizing highlights the inability of most corporations to really use their most valuable resource: the knowledge and creativity residing in the minds of employees.

The solution is a fundamentally different approach that harnesses the talents lying dormant in people. While Fortune 500 dinosaurs downsized by three million employees during the 1990s, smaller firms and new ventures upsized by creating 21 million new jobs. This salient fact shows that the key to vitalizing organizations is to bring the liberating power of small enterprise inside of big business.

In short, we need to shift the locus of power from top to bottom, to think of management in terms of enterprise rather than hierarchy. This may sound revolutionary, but today’s revolution is as dramatic as the Industrial Revolution. We tend to hear the Information half of the Information Revolution but to ignore the Revolution half. Just as the idea that Communism might yield to markets seemed preposterous a few years ago, similar change is needed in big corporations: “Corporate Perestroika”. Robert Shapiro, CEO of Monsanto, put it this way: “We have to figure out how to organize employees without intrusive systems of control. People give more if they control themselves” (Shapiro, 1997).

This introductory chapter reports the results of my studies focusing on hundreds of examples of internal enterprise being used to solve problems directly, creatively, and quickly. Pay-for-performance plans are being expanded to form self-managed units that are held accountable for results but free to choose their co-workers, leaders, work methods, suppliers, and generally “run their own business” as they think best. Line and support units are being converted into profit centers that buy and sell from each other and from outside the company, converting former monopolies into competitive business units. MCI, ABB, Johnson & Johnson, Hewlett-Packard, Lufthansa, and other companies have developed fully decentralized bottom-up structures that form complete “internal market economies” with hundreds of autonomous business units (Halal et al., 1993). These internal enterprises may buy and sell to other units within the company, compete with one another, and even work with outside competitors. The same trend can be seen in “reinventing government” and introducing competition into education (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992).

It takes only a little imagination to extend these trends to the point where the logic of free markets governs rather than the logic of hierarchy. The concept of internal markets has profound implications because it shifts the source of knowledge, initiative, and control from top to bottom, thereby providing the same benefits of external markets: better decisions through price information, customer focus, accountability for economic results, and as much entrepreneurial freedom as possible. One of the central implications is the need for “internal marketing” between internal enterprises – the subject of this book.

Yes, markets are messy, but they are also bursting with creative energy; roughly like the Internet, our best model of self-organizing market systems. Nobody could possibly control the Internet’s complex activities, yet by allowing millions of people to pursue their own interests, somehow the system grows and thrives beyond anything we could imagine.

In the final analysis, only a new form of management based on enterprise can meet the challenges lying ahead in a knowledge economy. The vague hope that participation, team spirit, inspiring leadership, and other worthy but limited ideas can co-ordinate tens of thousands of people into truly dynamic, entrepreneurial organization is little more than pious wishing. Mayor Steve Goldsmith of Indianapolis reports that he struggled for years trying today’s popular management methods, but nothing really changed until he turned the city’s departments into self-supporting units competing with outside contractors.

Principles of internal markets

It has become a cliché to note that business schools are notorious for their poor management. Mine was no exception. An especially irksome problem was getting the copy centre to work properly. Professors thrive on paper, yet we could not seem to get copies made in less than a week. We knew that our local Kinko’s could get them done in a day, but we would have to pay. Since the copy centre was free, we kept using it despite bad service. In fact, that is one reason why the service was bad: we overused this free good, clogging the system. Repeated attempts to get the copy centre to improve its operations, and the faculty to curb their excessive usage, had little effect.

The problem was that we were relying on a hierarchical assignment of tasks that were too complex for this approach. We needed good service. We needed faculty accountability. We needed a copy centre manager who was motivated to help us. We needed a choice of providers. In short, we needed a market.

After much argument, we asked the copy centre manager (let’s call him Art) if he would like to turn the operation into “his own business”. He could still use the school’s copiers and facilities to serve the faculty’s needs, but his income would be based on a percentage of the profits. The departments would get his old budget and could use it to either patronize Art or other copy centres. Art had an entrepreneurial streak, so he welcomed the opportunity.

Well, everything changed within days. A few people went to Kinko’s, which got Art thinking about how to improve operations. And having to pay now, the faculty carefully considered whether or not they really needed a hundred copies of their latest tome. Our copy centre’s service soon matched Kinko’s, Art became a celebrated hero, and the problem was solved – by an internal market.

This little story illustrates the power of a dramatically different concept that has been emerging quietly for years to realize the ideal of internal enterprise. To move us beyond the confining logic of hierarchy, an entrepreneurial management framework has been defined by Jay Forrester, Russell Ackoff, Gifford and Elizabeth Pinchot, and myself (Forrester, 1965; Ackoff, 1981; Pinchot and Pinchot, 1994; Halal et al., 1993), that views organizations as markets – “internal markets”.

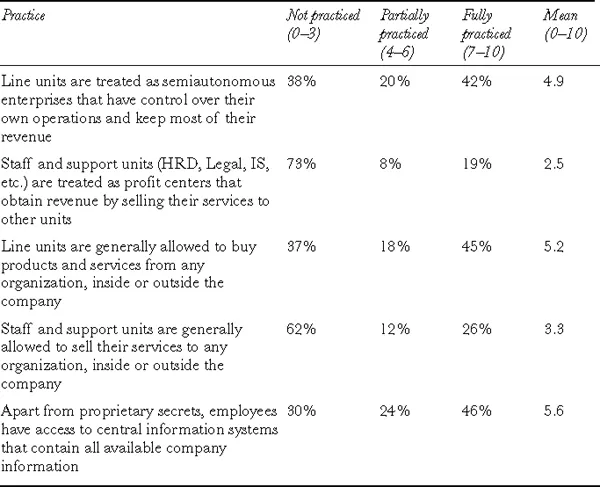

Internal markets are metastructures, or processes, that transcend ordinary structures. Unlike fixed hierarchies or centrally-coordinated networks, they are complete internal market economies designed to produce continual, rapid structural change, just as external markets do. Although only a few companies have implemented this idea as yet, Table 1.1 shows fairly wide acceptance of some key features, and the examples in the display on pp. 7–8 demonstrate various approaches that have been used.

Table 1.1 Adoption of internal market practices (sample = 426 corporate managers)

Source: Halal, The New Management (Berrett-Koehler, 1998).

Principles of internal markets

1 Transform the hierarchy into internal enterprise units. Rather than departments, “internal enterprises” form the building blocks of an internal market system. All line and staff units are transformed into enterprises by becoming accountable for performance but gaining control over their operations, as an external enterprise does. Alliances between internal enterprises link corporations together into a global economy.

2 Create an economic infrastructure to guide decisions. Executives design and regulate the infrastructure of this “organizational economy,” just as governments manage national economies: establishing common systems for accounting, communications, incentives, governing policies, an entrepreneurial culture, and so on. Management may also encourage the formation of various business arrangements that exist in an economic system: venture capital firms, consultants, distributors, and so on.

3 Provide leadership to foster collaborative synergy. An internal economy is more than a laissez-faire market, but a community of entrepreneurs that fosters collaborative synergy: joint ventures, sharing of technology, solving common problems, and so on among both internal and external partners. Corporate executives provide the leadership to guide this internal market by encouraging the development of various strategies.

Exemplars of internal markets

Johnson & Johnson’s 168 separately chartered companies form their own strategies, relationships with suppliers and clients, and other business affairs. CEO Ralph Larsen says the system “provides a sense of ownership that you simply cannot get any other way.”

Motorola uses autonomous units that compete with one another to produce the most successful products in America. One manager said: “The fact that I may conflict with another manager’s turf is tough beans. Things will sort themselves out in the market.”

Cypress Semiconductor defines each business unit as a separate corporation and support units from manufacturing subsidiaries to testing centers sell their services to line units. The CEO, T.J. Rodgers, says “We’ve gotten rid of socialism in the organization.”

Merck & Company has been rated the top Fortune 500 company because researchers pool their efforts in projects they choose, merging talents and resources into a new team. The CEO said: “Everybody here gravitates around a hot project. It’s like a live organism.”

Clark Equipment survived Chapter 11 by requiring all business units with a staff of 500 people or more to become self-supporting enterprises. Within months, staff decreased by 400 positions, costs were reduced across the company, and sales moved upward.

Alcoa revitalized a bureaucracy by converting all units into suppliers or clients that were free to conduct business with outside competitors. This dose of economic reality doubled productivity, and support groups brought in outside business.

Xerox is transforming itself from a functional hierarchy into an internal market composed of nine independent...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Context

- Part II: Structure

- Part III: Management/competency

- Part IV: Communication and service delivery

- Part V: Developments

- Part VI: Conclusion

- Index