![]()

1 ‘Just a Couple More Minutes of Your Time, About the Same Duration as the Rest of Your Life’: Making a Cult Vampire Film

In 1988, the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City singled out independent horror film Near Dark (1987), made by up-and-coming director Kathryn Bigelow, for special attention. Recognizing the film’s originality and artistry, MOMA honoured the film by presenting it as part of their Cineprobe programme. Launched in 1968, Cineprobe was designed as a forum ‘for independent and avant-garde filmmakers to present their work’. Films included in these seasons usually represented experimental and avant-garde cinema, ‘as well as narratives with new and unusual strategies’.1 Near Dark was screened on the 25 and 26 April 1988 – six months after the film’s theatrical release – accompanied by a mini-retrospective of Bigelow’s earlier films, notably her short, The Set Up (1978), and her first feature, The Loveless (1981), co-directed by Monty Montgomery.2 The inclusion of Near Dark in MOMA’s programme – as well as its acquisition into the MOMA collection – signals its position as a genre film that pushes boundaries and challenges conventions, while equally possessing a distinct narrative and aesthetic style. MOMA’s retrospective also marked early recognition of Bigelow as a significant film-maker and auteur. Moreover, as J. Hoberman in the Village Voice noted, Near Dark was ‘the first horror flick to be given a Museum of Modern Art Cineprobe since the epochal June 1970 screening of Night of the Living Dead helped crystallize that movie’s cult’.3 The association with Night of the Living Dead in this context draws attention to certain symmetries between the films. Both failed upon initial theatrical release only to find critical and curatorial acceptance within broader film culture and, eventually, an audience through alternative channels – the Midnight Movies of the 1970s for Night and video/laserdisc/DVD release for Near Dark. Both are also horror films that challenge expectation, signalling the value and artistic potential inherent to the genre.

Near Dark is a vampire film set largely in the contemporary Midwest of the USA that rejects established genre conventions in favour of its own hybrid approach. It skilfully merges the Gothic with the conventions of the western, road movie and film noir at a narrative and aesthetic level, while also introducing elements of the outlaw romance genre of They Live by Night (Nicholas Ray, 1948) and Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967). Near Dark tells the story of Caleb, a half-vampire trying to decide whether to embrace his new nature or return to his human family. It is the family of vampires who lure him into their nocturnal existence that is of central importance to the film’s innovation. They are defined by a nomadic lifestyle, anarchic behaviour, a passion for violence, an ambition for eternity, intense family bonds, and a gritty visual appearance. They are morally ambiguous and undermine the class structures that have historically defined stories of the undead. These are not aristocrats but instead they capture the allure and horror of the disenfranchised and the underclass.

The film is sumptuous in its aesthetic design, offering a nuanced and haunting presentation of its monstrous protagonists who stalk the backroads and desert landscape of the American Midwest. While it remains Bigelow’s only foray into horror to date, its innovation showcases the creativity and artistic richness of the genre without sacrificing its visceral qualities. The film’s reception by MOMA signals Bigelow’s standing as a director of significance at an early point in her career, not simply because of her visual art background, something that would be in keeping with many of the artists featured in the Cineprobe series, but because of the way in which she would from Near Dark onward re-envision traditionally mainstream genres of film-making.

Production

Before making Near Dark, Bigelow co-wrote and co-directed The Loveless with Monty Montgomery, a film that is equally preoccupied with outcasts and outlaws existing on the periphery of society. While there are clear connections to Near Dark, its aesthetic and narrative drive is drawn more from Bigelow’s experience as an artist than her growing fascination and interest in working in mainstream cinema. The Loveless is a low-budget motorcycle movie with art cinema leanings, made for $800,000 raised from private funders. It was shot over six weeks and premiered at the Locarno Film Festival in 1981.4 Bringing together the styles and preoccupations of Douglas Sirk and Kenneth Anger, Bigelow and Montgomery conceived of the film as a ‘drive-in movie with psychological connotations’. Lindsay Mackie observed that the film uses its biker narrative to explore themes around ‘incest and the character of the South itself, its repressiveness, the dejected hatred of outsiders’.5 After The Loveless’ release, Bigelow entered an unsatisfying period of project development, writing scripts for Walter Hill and Touchstone Studios, among others, that were never realized, while also working as a film studies lecturer. Teaching a class on ‘B-movies’ at Cal Arts, Bigelow honed her interest in low-budget genre film-making.6 Near Dark therefore marked Bigelow’s first solo directorial outing and the gateway to what would become an illustrious career as a leading director working in Hollywood cinema.

Near Dark was co-written with Eric Red, who also collaborated with Bigelow on Blue Steel (1990), as well as writing The Hitcher (Robert Harmon, 1986) and writing/directing Body Parts (1991) and Bad Moon (1996). Near Dark was their first collaboration and was part of an arrangement between Bigelow and Red designed to launch their careers as writer-directors. They agreed they would co-write two non-commissioned screenplays, which they would attempt to finance, with themselves attached as directors to help gain their foothold within the industry. They co-wrote Near Dark and Undertow with Bigelow attached to direct Near Dark and Red to direct Undertow (1996). Bigelow and Red sent the script for Near Dark to independent film producer Edward S. Feldman and his company F/M for financing. Feldman had recently had notable critical and box-office success with Witness (Peter Weir, 1985) and was, along with F/M partner Charles R. Meeker, the executive producer of The Hitcher. Feldman says that ‘at the time we were looking for low budget original scripts. There are a lot of low budget films but most of them don’t have any real pizzaz to them. This show had a lot of pizzaz to it’.7 Feldman and Meeker received the script on Thursday and a deal was agreed by Monday and Bigelow’s commercial directorial career began in earnest.8 Steven-Charles Jaffe – associate producer of Demon Seed (Donald Cammell, 1977) and Time After Time (Nicholas Meyer, 1979), producer and writer of Motel Hell (Kevin Connor, 1980), and director of Scarab (1983) – came on board as producer. Adam Greenberg (The Terminator [James Cameron, 1984]), described by Feldman as the ‘celebrity independent DP’ of the period, was director of photography;9 Howard Smith (River’s Edge [Tim Hunter, 1986]) was the editor; and Stephen Altman (Secret Honor [Robert Altman, 1984] and Fool For Love [Robert Altman, 1985]) was production designer. The film was made for a budget of $5 million. Near Dark’s indie credentials were in place with a production team emerging from American low-budget cinema tradition, all under the helm of Bigelow.

Originally due to be shot in Oklahoma, the film had to be relocated at the last minute to Coolidge, Arizona, due to flooding. It had a very tight and difficult schedule, shot over forty-seven days of which forty were night shoots. In addition to co-writing the script, Bigelow produced precise, visually dynamic storyboards, and while Bigelow explains that they ‘didn’t nail [their] feet to the (story) boards’, the tight schedule meant that they did follow them closely rather than improvise on location.10 Feldman and Jaffe, as well as the cast, praised Bigelow for her professionalism and vision for the film. Unfortunately, the first major problem occurred during post-production near the end of the summer 1987 when the production company F/M lost their distribution deal for the film. By September 1987, however, the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG) had acquired domestic, and limited international, distribution rights for the film but unfortunately DEG went bankrupt during the film’s release. These distribution problems impacted on how the film was marketed and subsequently on its box-office reception.11

Reception

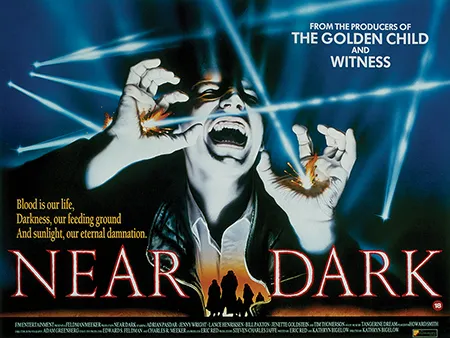

Near Dark premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September and was released on 2 October 1987, marketed as a Halloween horror release. Posters were varied but generally featured horror elements such as the bloody and burnt image of Bill Paxton as the vampire Severen or the screaming face of a vampire shot through with beams of sunlight. The tagline ‘Blood is our life, Darkness, our feeding ground; And sunlight, our eternal damnation’ also emphasized the film’s horror heritage. Near Dark played in US cinemas for approximately three weeks, bringing in a total domestic box-office gross of $3,369,307, a poor return given its $5 million budget.12 These box-office results are in some ways surprising, particularly considering the growing popularity of the vampire at this time. The 1980s marked a notable return to the vampire in American horror cinema, with a particular shift toward the Americanization of the genre through its relocation away from Europe – and its more conventionally Gothic roots – to modern day USA with films such as The Hunger (Tony Scott, 1983), Fright Night (Tom Holland, 1985), Once Bitten (Howard Storm, 1985), Vamp (Richard Wenk, 1986), The Lost Boys (Joel Schumacher, 1987), The Monster Squad (Fred Dekker, 1987), Fright Night Part II (Tommy Lee Wallace, 1989) and Vampire’s Kiss (Robert Bierman, 1989). Most of these films were R-rated and updated the vampire genre by mixing horror with teen comedy. Once Bitten and The Monster Squad targeted a broader and younger audience (both PG 13) but took a similar approach to revisioning the genre, while The Hunger and Vampire’s Kiss bookend the period with New York-centric, reimaginings of the vampire with art-house leanings. This backdrop surrounding the popularity of the genre, enhanced by the success of Anne Rice’s novels Interview with the Vampire (1976) and The Vampire Lestat (1985), is perhaps what made Near Dark appealing to its producers and financers, seeming to tap into a popular trend but offering a unique twist.13 Bigelow has commented that ‘Near Dark started because we wanted to do a western. But as no one will finance a western we thought, okay, how can we subvert the genre? Let’s do a western but disguise it in such a way that it gets sold as something else. Then we thought, ha, a vampire western.’14

A Halloween horror release

The degree to which the vampire films in this period were successful varies, with Fright Night (released August 1985) earning $24,922,237 at the domestic box office and Once Bitten (released November 1985) followed by Vamp (which was released in July 1986), bringing in box-office results of $9,917,242, and $4,941,117 respectively. In contrast, The Lost Boys, released three months before Near Dark and with a production budget of $8.5 million, exceeded Fright Night by earning $32,222,567 at the domestic box office. While The Lost Boys and Near Dark have certain narrative similarities – each presented as a coming of age story about a young man who has to choose between the responsibilities of adulthood and the freedom of life as a vampire – the differences that impacted upon their box-office reception are notable. Near Dark was independently financed and distributed, while The Lost Boys was a studio product made by Warner Brothers. The Lost Boys, therefore, not only benefited from a bigger production budget but also a more extensive marketing campaign that made it significantly more visible. Bigelow was a comparatively unknown director, while director Joel Schumacher was a more established studio film-maker, whose previous film, St. Elmo’s Fire (1985), had earned over $37 million at the US box office and starred Brat Pack icons Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, Judd Nelson, Rob Lowe, Demi Moore and Andrew McCarthy. Capitalizing on this formula, The Lost Boys starred Kiefer Sutherland, Jami Gertz, Corey Haim and Corey Feldman, similarly recognizable from teen movies and TV series such as Stand By Me (Sutherland and Feldman), Silver Bullet (Haim) and Square Pegs (Gertz). Near Dark starred Lance Henrikson, Jenette Goldstein and Bill Paxton in supporting roles, recognizable at the time from James Cameron’s Aliens (1986), as well as Joshua Miller familiar to some from the indie film River’s Edge, but the main stars, Adrian Pasdar and Jenny Wright, were comparative unknowns.

Significantly, The Lost Boys opened on 1,025 screens while Near Dark opened on 262 screens in the United States, going up to 429 in its second week. At the time of Near Dark’s entry into the charts, The Lost Boys was in its eighth week in the US charts, still playing on over 400 screens. Similarly, Fright Night opened on 1,542 screens; Once Bitten on 1,095 screens, Vamp on 1,104 screens, and The M...