Introduction to Non-Invasive EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces for Assistive Technologies

- 84 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Introduction to Non-Invasive EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces for Assistive Technologies

About this book

This book aims to bring to the reader an overview of different applications of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) based on more than 20 years of experience working on these interfaces. The author provides a review of the human brain and EEG signals, describing the human brain, anatomically and physiologically, with the objective of showing some of the patterns of EEG (electroencephalogram) signals used to control BCIs. It then introduces BCIs and different applications, such as a BCI based on ERD/ERS Patterns in ? rhythms (used to command a robotic wheelchair with an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system onboard it); a BCI based on dependent-SSVEP to command the same robotic wheelchair; a BCI based on SSVEP to command a telepresence robot and its onboard AAC system; a BCI based on SSVEP to command an autonomous car; a BCI based on independent-SSVEP (using Depth-of-Field) to command the same robotic wheelchair; the use of compressive technique in SSVEP-based BCI; a BCI based on motor imagery (using different techniques) to command a robotic monocycle and a robotic exoskeleton; and the first steps to build a neurorehabilitation system based on motor imagery of pedalling together an in immersive virtual environment. This book is intended for researchers, professionals and students working on assistive technology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Review of the Human Brain and EEG Signals

CONTENTS

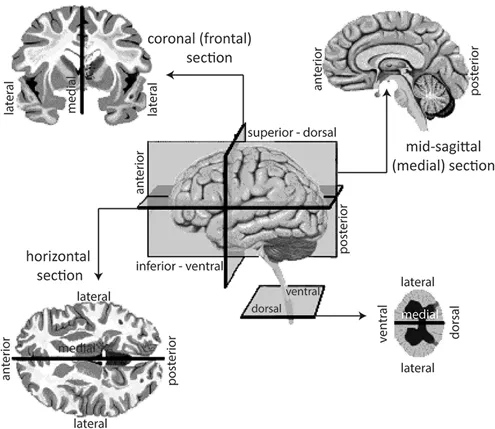

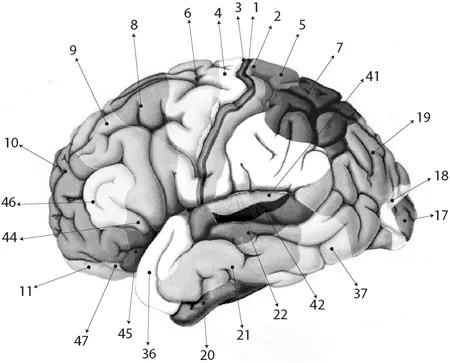

1.1 Planes of Section and Reference Points of the Human Brain

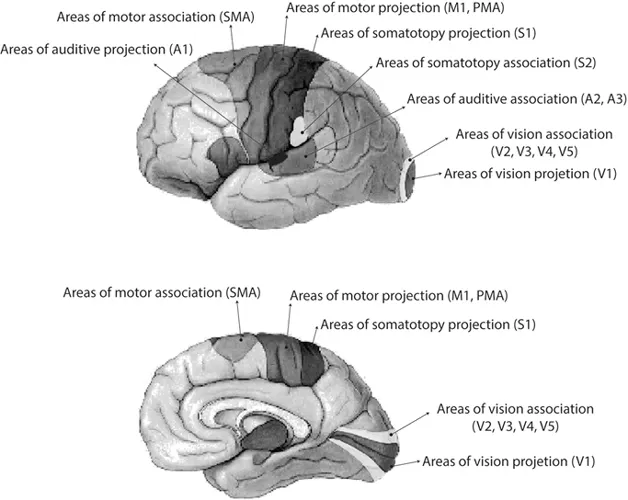

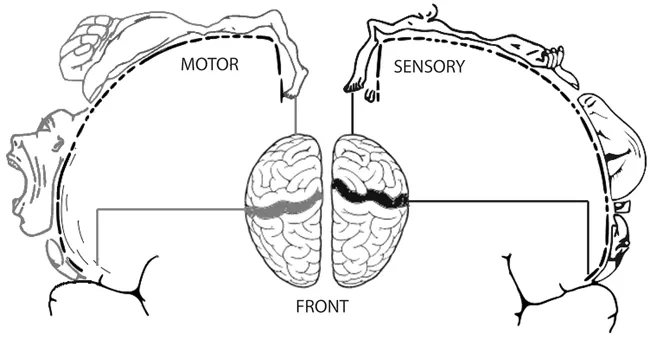

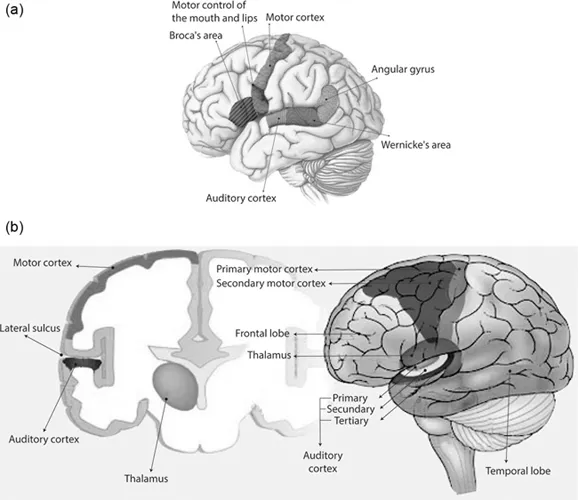

1.2 Details of S1, M1, A1, V1, Wernicke’s, and Broca’s Areas

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editor

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Review of the Human Brain and EEG Signals

- Chapter 2 Brain–Computer Interfaces (BCIs)

- Chapter 3 Applications of BCIs

- Chapter 4 Future of Non-Invasive BCIs

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app