- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Beyond border walls and prison cells—carceral society is everywhere. In a time of mass incarceration, immigrant detention and deportation, rising forms of racialized, gendered, and sexualized violence, and deep ecological and economic crises, abolitionists everywhere seek to understand and radically dismantle the interlocking institutions of oppression and transform the world in which we find ourselves. These oppressions have many different names and histories and so, to make the impossible possible, abolition articulates a range of languages and experiences between (and within) different systems of oppression in society today.

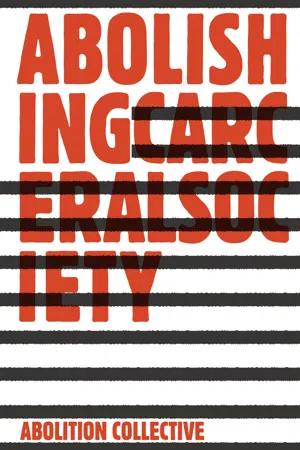

Abolishing Carceral Society presents the bold voices and inspiring visions of today’s revolutionary abolitionist movements struggling against capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism, ecological crisis, prisons, and borders.

In the first of a series of publications, the Abolition Collective renews and boldly extends the tradition of “abolition-democracy” espoused by figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Angela Davis, and Joel Olson. Through study and publishing, the Abolition Collective supports radical scholarly and activist research, recognizing that the most transformative scholarship is happening both in the movements themselves and in the communities with whom they organize.

Abolishing Carceral Society features a range of creative styles and approaches from activists, artists, and scholars to create spaces for collective experimentation with the urgent questions of our time.

Through essays, interviews, visual art, and poetry, each presented in an accessible manner, the work engages with the meaning, practices, and politics of abolitionism in a range of historical and geographical contexts, including: prison and police abolitionism, border abolition, decolonization, slavery abolitionism, antistatism, antiracism, labor organizing, anticapitalism, radical feminism, queer and trans politics, Indigenous people’s politics, sex worker organizing, migrant activism, social ecology, animal rights and liberation, and radical pedagogy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

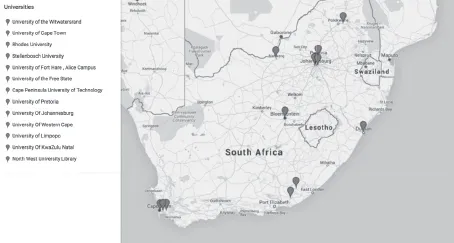

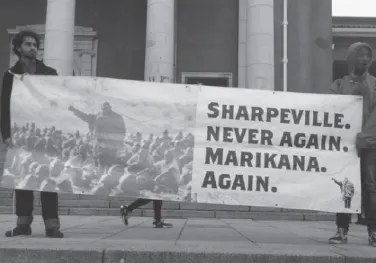

SOUTH AFRICAN STUDENTS’ QUESTION

FROM “RHODES MUST FALL” TO “FEES MUST FALL” TO “THE DEATH OF A DREAM”

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- About Abolition

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Manifesto of the Abolition Journal

- Intervention | Long Live John Africa!

- Art | Make Racists Afraid Again

- Intervention | Dismantle and Transform: On Abolition, Decolonization, and Insurgent Politics

- Art | After My Pa Cut the Grass

- Article | Shifting Carceral Landscapes: Decarceration and the Reconfiguration of White Supremacy

- Art | Shadow Boxing: A Chicana’s Journey from Vigilante Violence to Transformative Justice

- Intervention | With Immediate Cause: Intense Dreaming as World-Making

- Poetry | A Matter of National Security

- Art | The Horrors of Womanhood

- Intervention | Crafting the Perfect Woman: How Gynecology, Obstetrics and American Prisons Operate to Construct and Control Women

- Art | Guard Tower

- Article | “Prison Treated Me Way Better Than You”: Reentry, Perplexity, and the Naturalization of Mass Imprisonment

- Intervention | Mass Incarceration is Religious (And so is Abolition): A Provocation

- Art | Opiate of the Masses

- Intervention | We Don’t Need No Education: Deschooling as an Abolitionist Practice

- Art | If you want you can have

- Intervention | South African Students’ Question: Remake the University, or Restructure Society?

- Poetry | On Objections to Pledging Allegiance

- Poetry | Check One

- Article | All our Community’s Voices: Unteaching the Prison Literacy Complex

- Intervention | Revolution and Restorative Justice: An Anarchist Perspective

- Art | Untitled

- Poetry | (In)Visibility

- Intervention | Lessons on Abolition from Inside Women’s Prisons

- Poetry | Ailments

- Intervention | #ResistCapitalism to #FundBlackFutures: Black Youth, Political Economy, and the Twenty-first Century Black Radical Imagination

- Poetry | I Seen Something

- Intervention | Reflections on White Supremacy

- Art | Plague

- Poetry | Whole Foods

- Intervention | Toward an Abolition Ecology

- About the Contributors

- Index

- About Common Notions

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app