![]()

CHAPTER

1

Gearing Up to License Your Invention

Licenses

When You License, You Are Leasing Your Legal Rights

Licenses Can Be Flexible

Licenses Can Be Written or Oral

Assignments

The Licensing Process

Meet and Greet the Potential Licensee

Negotiating the License

Execution and Monitoring

Avoiding Conflicts Among Multiple Agreements

Agreements That Can Affect Licensing

Keeping Track of Agreements

Challenges to Your Ownership

Types of Ownership Challenges

Dealing With Ownership Challenges

Transferring Ownership of Your Invention to Your Business

Sole Proprietorships

General Partnerships

Limited Partnerships

Corporations

How Do You Transfer Ownership of Your Invention to Your Business?

Disclosing Information About Your Invention

Keeping Your Records

Keep an Inventor’s Notebook

Use Nondisclosure Agreements

Maintain a Business Notebook and Files

Insist on Written Agreements

No False Hopes! Reviewing Your Invention’s Commercial Potential

The SBA’s Four Tests for Commercial Potential

The Innovation Center’s Factors for Commercial Potential

The Patent It Yourself Factors for Commercial Potential

Testing the Waters Yourself

Getting an Expert Opinion

What If There Is No Commercial Potential?

Eureka! You’ve developed an invention and believe it has commercial potential. What’s next? For many inventors, the best way to profit from an invention is to have someone else—usually a company that already specializes in similar products—develop, manufacture, or market the invention. However, since an inventor holds ownership rights (sometimes called title) in an invention, another company cannot do these things unless the inventor gives permission. Broadly speaking, this permission is called a license.

This chapter will give you an overview of the licensing process and help you screen out potential problems that could hinder your ability to license your invention. Review this chapter if you answer “yes” to any of the following questions:

• Would you like an explanation of the difference between a license and an assignment?

• Do you want a brief description of the legal rights related to your invention?

• Have you signed any documents regarding your invention?

• Would you like an understanding of who might own your invention besides yourself?

• Have you shown your invention to—or discussed it with—anyone?

• Do you want some help in keeping track of your business transactions?

• Would you like information about how to assess the potential value of your invention in the marketplace?

What We Mean by an Invention

The term “invention” as used throughout this book refers to any innovation, device, or process that can be commercially used or developed. Although the strongest form of protection for your invention is a patent, this book does not deal solely with patented or patentable inventions. Many inventions might not qualify for patent protection but can be protected under some other legal principle, such as trade secret or copyright. If your invention has commercial potential and is protectable under some form of intellectual property law, you can use this book to help you license it to others. See Chapter 2 for an overview of the different ways your invention may be protected.

Licenses

A license is an agreement in which you let someone else use, develop, or reproduce your invention for a period of time. In return, you receive compensation—either a onetime payment or continuing payments called royalties. Your power to make this kind of agreement is based on the premise that you control the right to make and sell your invention—which, in turn, depends upon whether your invention is protected under intellectual property laws. (See Chapter 2.) If your invention cannot be protected under intellectual property laws, it’s unlikely you will license your invention. Why? Because, if your invention is not protected, anyone can make and sell it. So, why should they pay you?

If your invention is protectable, you can stop others from making or selling it. In other words, a company can make and sell a “protected” invention only if you give them permission. By negotiating a license, a company can make, sell, or use your invention without fear of a lawsuit, as long as it abides by the terms of the license. Basically, a license gives the company a right to do something it would otherwise be prohibited from doing.

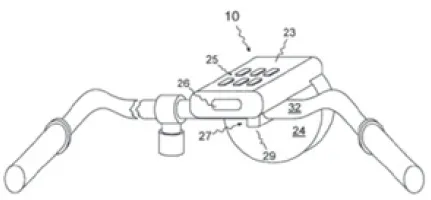

Voice Alert System for Use on Bicycles

No. 6,317,036

You Are the Licensor, They Are the Licensee

For purposes of this book, you—as owner of the invention—will always be the licensor, and the company using or reproducing your invention is called the licensee.

According to legal practice, the person who is the source of the activity gets an “er” or “or” suffix (such as employer, lessor, discloser). The person who is the recipient of the activity gets an “ee” (such as employee or lessee).

When You License, You Are Leasing Your Legal Rights

A license for an invention is similar to a lease for a house or an apartment. A tenant makes periodic payments to an owner of property for the right to use it. If the tenant fails to honor the terms of the lease or rental agreement, the owner can reclaim possession and make the tenant leave. Similarly, a licensee pays you royalties (similar to rent) for the right to manufacture, sell, or use your invention for a period of time. If the licensee fails to pay you or otherwise breaches your agreement, the agreement may terminate and, provided the license is drafted properly, you can license your invention to someone else.

It’s also important to realize that you do not license the invention itself. Rather, you license your legal rights to the invention. This distinction causes confusion for some inventors. Legal rights —patent, copyright, trademark, or trade secret rights—are what give you title or ownership of the invention, much like a deed to a house gives you title to the property. When you license your invention, what you are really transferring to the licensee are your legal rights, such as your rights to manufacture, sell, and use the invention. These legal rights will be explained in more detail in Chapter 2. It’s beyond the scope of this book to assist you in securing intellectual property protection. In Chapter 18, “Help Beyond This Book,” we refer you to other resources for protecting intellectual property.

For now, keep in mind that the primary goals in licensing are to:

• determine what legal rights you have

• acquire the appropriate protection for those rights, and

• license those rights to others who can pay you for the privilege.

Licenses Can Be Flexible

A license agreement can be drafted according to the specific needs of the licensor or licensee. For example, you can limit the license of your invention for a period of time, such as one year. You can limit the license to a certain area, such as Canada. You can even license your invention to more than one manufacturer at one time.

EXAMPLE: Joe invented a patented flotation device. Two companies are interested in it: a toy company and a company that makes boating products. Joe can sign two license agreements and earn royalties for both uses.

Because a license can be as flexible as the parties wish it to be, the task of drafting a license typically involves much more than simply agreeing to standardized language often found in legal agreements. That is what this book is all about—teaching you how to draft a license agreement that is just right for you. Drafting a license agreement is covered thoroughly in Chapter 8.

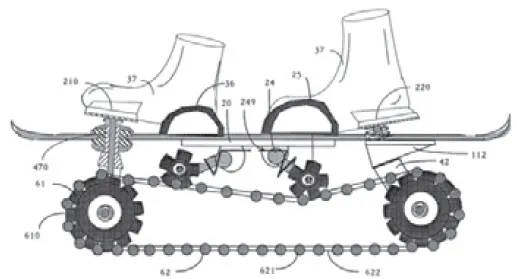

Frictionless Noncontact Engaging Drive Skate & Skateboard No. 6,007,074

Forms of Intellectual Property

Because licensing basically involves lending your legal rights to someone else, it’s crucial that you know precisely which legal rights are associated with your invention. These rights are sometimes referred to as “proprietary rights” or “intellectual property rights.” Below are the intellectual property rights associated with inventions. Chapter 2 provides more information on intellectual property.

Utility patents protect inventions (functional devices and processes) that are new and unique. When you have a utility patent, you can stop others from making, selling, or using your invention. You must apply for and receive a patent from the federal government before you have patent rights in the United States.

Design patents protect decorative designs that are used on functional devices. You must acquire a design patent from the federal government before you have design patent rights. As with utility patents, you can’t stop illegal copying of your design until your design patent has been issued.

Trade secret law protects confidential information that gives you an advantage over competitors. You must treat the information with secrecy and disclose it only to those who agree to keep it secret. No registration is necessary, as registration would defeat the confidentiality requirement. A trade secret is sometimes an alternative or complement to patent protection, particularly for inventors who don’t wish to make their methods or processes public. An inventor can also use trade secrets as a form of protection during the period between applying for and getting a patent.

Copyright protects the artistic expression contained in writing, software, art, music, dance, architecture, and movies. Copyright does not protect functional objects, such as clothing or furniture; it protects only the artistic elements, such as fabric designs or ornamental furniture legs. You have copyright protection under the law as soon as you create...