![]()

ONE

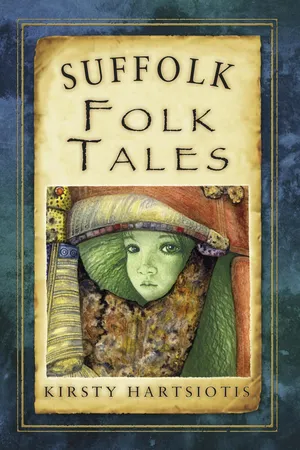

THE GREEN

CHILDREN

During the reign of King Stephen, Aylwin and Elstan of Woolpit were on their way through the woods to check their snares. They knew they had to be careful with their footing in this part of the wood, as there were pits in the claggy ground and blocks of old brick to trip over. The place was snarled with brambles and nettles; hardly a proper wood at all. No one came here, as it was said to be infested with wolves. Ideal for poaching.

That day they made their way up the slope about a mile from Woolpit, on the way to Elmswell. One snare held a young hare, which pleased them, but the rest were empty. Then Elstan caught a movement out of the corner of his eye.

‘Get out your sling,’ he whispered. ‘There’s something there.’

The two of them crept forward, further up the hill towards Elmswell, Alywin with his sling at the ready, until the ground suddenly dipped into a large bramble-filled pit. Elstan slipped, skidded and fell, and a scream filled the air.

A child’s scream.

They peered into the pit, and there, huddled among the brambles, were two children. The children were dressed in rough homespun like themselves, but there the similarity ended. These children were green from their thick hair down to their bare toes.

Aylwin and Elstan froze. Green was an unlucky colour, a fairy colour. But these were just children. The older, a girl, looked to be about nine or ten years, the boy several years younger. They were scratched and weeping, and didn’t look like a threat.

‘Who are you?’ asked Elstan. ‘How did you get here? Where are your folks?’

The children stared back at him, and the men realised that they couldn’t understand English. So Aylwin waded down into the pit and picked them up. They didn’t fight; just wept some more.

Back in Woolpit, the whole village turned out to see the wonder. It was soon decided that they couldn’t keep the children in Woolpit. Who would feed them? And would their landlord, the Abbot at Bury, approve of the ungodly things? Better to take them to someone who would find amusement in their novelty.

It was decided they should go to Sir Richard de Calne at Bardwell, eight miles away. He was the Constable of the Hundred, and would know what to do. Aylwin and Elstan were volunteered to take them. It was a long trek for the children. They wept as the men chivvied them on, step by step, until they came to the edge of Bardwell.

There were three manors in Bardwell. Unsure where to go, the Woolpit men went first to Wyken Hall. The servants there drove them away with fleas in their ears. Past Bardwell Hall they went, until at last they saw the squat tower of the church on a low hill ahead of them, and right beside it, the manor house of Wikes.

Sir Richard received the green children with grave thanks and gave Aylwin and Elstan some coins to see them on their way.

‘You’ll see them treated right, my lord?’ asked Aylwin. ‘Them’s just children, when all’s said and done.’

‘No harm will come to them here,’ said Sir Richard.

The children were brought before him, tear and travel stained. They really were very green. But it was only fair to try to communicate with them. He knew that the villagers would only have their own English, so he tried his Norman-French, and when that didn’t work he tried a few words of Flemish. Neither had any effect, save to make the children cry even more.

His wife, Sibylla, leaned forward and whispered, ‘Perhaps the poor mites are hungry. You can be sure those villeins wouldn’t have given them anything from their stores.’

So bread and cider and good meat were set before them. But the children just stared at the spread as if it was poison. Even when Lady Sibylla tore off some bread and ate it herself to give them the idea, the children just wept. The lord and lady looked at each other. Unspoken between them was the thought that this newly brought marvel would not last that long.

Just at that moment, a maid came in from the gardens with baskets of broad beans, and as she walked past, both the children sat up and pointed.

‘Bring those beans here,’ cried Lady Sibylla, and she handed the basket to the children.

Immediately the children started pulling at the beans, but instead of trying to open the pods, they opened the stems. When they saw that they were empty, the tears started again. Lady Sibylla took the pods and snapped them open to reveal the beans inside. As soon as they saw the beans, both the children gave cries of joy and started to stuff the raw beans in their mouths.

After that, they settled into the household. Sir Richard saw to it that while they were set simple tasks by the servants, they also received instruction in English and French. He made the priest their tutor, as they seemed to have no knowledge of God.

The girl thrived under this care. Her long green hair and green skin soon glowed with health, and she was soon speaking a few simple words to make her needs known. The boy was different. After the bean harvest was over, the girl began to eat other things – vegetables at first, then bread, although she would never touch meat. But the boy wouldn’t eat. His sister tried to tempt him with all sorts of dainties that the kitchen staff gave her, but he just turned away. She tried taking him out just before sunrise and just after sunset, and that pleased him a little, but he shied away from the bright sunshine. Soon enough he was too sick to go out, and before harvest time was over he was dead.

Lady Sibylla spoke quietly to the priest, and he was buried outside the west end of the church, with the other unbaptised babes, to catch what holiness he could. His sister seemed grateful, but it was hard to tell.

The girl would walk out from the manor whenever she could, wandering over the Black Bourn and through the reed beds and the stubbly fields. All the field hands knew to watch her, in case she strayed too far, but she never did. She would come back with bunches of the harvest flowers; loosestrife, mallow and dead-nettles, take them to the little grave, and sit there quiet and alone.

By Christmas, her English and French were good and she happily ate anything that was put in front of her. She went less to the grave and was soon at the heart of the household, laughing with the servants, playing rowdy games with the other children and even flirting a little with Sir Richard’s pages. Sir Richard noticed, too, that the greenness of her skin had faded a little and her hair had gained yellow tints. The marvel might soon be gone, so he gathered his friends together for a great Christmas feast and brought the girl out.

There were gasps of fear from his friends, and Sir Richard realised how used he was to her strangeness. She didn’t seem worried by the crowd. When he drew her forward to speak, she stepped up on the dais without any fear.

‘Tell us, child, how you came here,’ he asked. ‘Tell us of your own home.’

The girl lifted her gaze to the assembled nobles. ‘My brother and I were herding our father’s sheep that day. Our land isn’t like yours, but we do herd and farm like you do. I did this every day, but he was new to it, being young. One of our lambs got lost, and we set out after it. We could hear him bleating, so we just kept on going until we were far from our home. It was coming on for night when we found him, and when we turned to go back we realised we didn’t know the way. So we just walked and walked, and then, in the darkness, we both fell, and we plummeted down a long way until we landed on dry earth and saw a tunnel stretching out. There were strange sounds all around us, sweet sounds, the like of which we’d never heard before, and those sounds drew us. We walked towards them. It seemed me that we walked all night. At last, we saw that there was light ahead, and we ran, hoping we’d be near our home, but as we came out the light was so bright that we both fell down in a faint. When we woke up those men were there, and they dragged us out, and it was so bright, and so strange, and we couldn’t understand them at all.

‘Our land isn’t like yours. Yours is so bright! I find it lovely now, the sunshine on the flowers, but at home the sun is always beyond – just a distant glow to the west. Like twilight, it is a gentle, quiet light. We’re all green. To see you pink people was a shock, but now it makes me laugh! And we would never eat the flesh of animals. It goes against all that is right. Our sheep were our friends; they gave us their wool so that we might be warm. But here everything is different. You have God to guide you – and the beautiful sound of the church bells that drew us here. Maybe it was God’s plan to bring us here … but’ – she glanced guiltily at Sir Richard – ‘sometimes I wonder if I went back to Woolpit I might find my way home.’

Her words were a sensation. No one talked of anything else for a season. But soon new stories came to take the place of the marvel. The girl began to change as well. She was baptised, and given a name: Agnes. Slowly, as the season passed from winter into spring and from spring into summer, her greenness dwindled away, until her skin was simply pale and her hair simply fair. Those who came seeking the green child went away disappointed.

But Sir Richard remembered what she had said. So he had his men take her to Woolpit. The two farmers, Aylwin and Elstan, were fetched, and they showed the girl where they had found her. But though the brambles were cleared, there was nothing to be seen there but heavy clay. After that, Agnes never mentioned her first home again. She threw herself into the life of Wikes Manor and seemed to want to forget her origins.

Sir Richard saw that, though she was baptised, there were some things that made her different. She still liked to wander alone by the stream at sunset. More worryingly, she was drawn to the young men and seemed to see nothing wrong in exchanging kisses with his squires. It was disruptive, and he worried that there would soon be a shame she couldn’t hide. With one of the lads, from Lynn in Norfolk, Sir Richard thought there was something more serious than just the flirting, so he gave Agnes a fine dowry, and she was married.

Agnes lived the rest of her life in Lynn, and gave birth to several children. None of them was green, but it was said that her descendants were all fun-loving and didn’t fear God as much as they should.

This is perhaps Suffolk’s most famous story and has been much written about. It comes from Ralph of Coggeshall, the sixth abbot of Coggeshall Abbey in Essex, who is best known for his work the Chronicon Anglicanum. Of his tales, three of them are set in Suffolk. There are many theories about why the children were green and couldn’t speak English. Were they the children of Flemish weavers? Did they walk through tunnels like those at Grimes Graves? Did they have an iron deficiency that produced anaemia? Or maybe they were simply from that other world.

![]()

TWO

FIVE SKEINS

A DAY

There was once a woman who baked five pies, enough for the week; but she forgot them in the oven. When she took them out, they were rock hard. She was a busy woman, so she called her daughter over and told her to put them in the pantry to let them come again. Her daughter, a lazy lass of sixteen, was amazed to hear that her mum could bake magic pies. She took them to the pantry, but even though they were rock hard, they smelt really good.

She thought to herself, ‘If they will come again, I might as well eat them now.’

So she did.

Later, when her mum came in hungry after working, she asked her daughter to fetch her one of the pies, ‘As surely they’ll have come again by now’.

The girl trotted back to the pantry, but there wasn’t a single pie come back again. She went back and told her mum so.

‘Are you sure?’ said her mother, shrugging. ‘I’m hungry; I’ll have one anyway.’

Her daughter stared at her.

‘You can’t – I ate them all, so you’ll just have to wait for them to come again.’

Her mother was furious. Had the girl learnt nothing? Surely everyone knew that when a pie ‘came again’, the pastry was just softening in the air? She took her spindle and sat outside, still fuming. As she span, a little song came to her.

‘My daughter ate five pies today, five pies.’

She repeated it over and over. It began to ease her anger. Just a little.

As she was sitting there spinning and singing, the King happened to come past on his fine horse. He overheard the woman singing, but couldn’t quite catch the words.

‘My good woman, what are you singing?’

The woman, embarrassed to be caught singing about her daughter’s stupid gluttony, quickly changed the rhyme: ‘My daughter spun five skeins today, five skeins.’

The King was impressed. His mother had been a great spinner and weaver, so he knew a little about such things.

‘I’ve never heard of anyone who could do that. Show me this daughter of yours.’

The girl was brought out, and the King looked her up and down. She was as pretty as only sixteen can be; plump-cheeked and rosy, her figure not yet showing what five pies a day can do. The King smiled at her.

‘I’ll make you a bargain,’ he said. ‘Marry me, and for eleven months you’ll have everything you want: fine food, fine clothes and as many servants as you like. But in the twelfth month you’ll spin me five skeins a day, and I’ll cut off your head if you don’t.’

The girl wasn’t very impressed with this, and was just about to open her mouth to refuse when her mother pulled her aside.

‘Don’t you do another foolish thing today! You say yes, and sure as sure with a young bride in his bed he’ll forget all about them five skeins.’

So the girl said yes. She was taken to the palace, and before she could turn round she was the Queen. It was fabulous: there was fine food and clothes and servants, just as he’d said – and the King himself wasn’t so bad, either. She soon forgot about the fi...