![]()

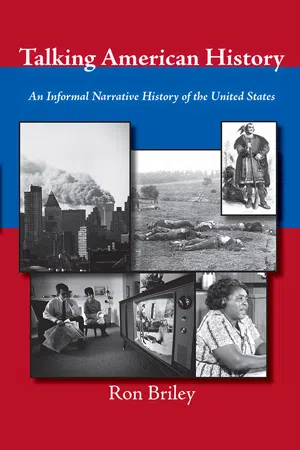

Talking American History

An Informal Narrative History of the United States

Ron Briley

For my mentors Pete Petersen and Dick Heath

and

The students of Sandia Preparatory School

Who taught me so much.

Introduction

Industrialist Henry Ford is touted to have dismissed the study of history by describing the discipline as one damned thing after another. Unfortunately, generations of history students in both the schools and universities might agree with Ford after suffering through endless formal lectures and massive textbooks filled with facts to be memorized. And the knowledge explosion of the internet has not necessarily made matters any better as our understanding of history is weighed down by even more “facts,” although this information is now available with one click on our computers. Buried under the avalanche of historical detail, students feel overwhelmed, and they understandably turn toward the more pragmatic STEM education with possible careers in science and engineering. Yet, these upcoming scientists are desperately in need of comprehending the historical and cultural context in which their research and discoveries will be implemented. In addition, academic specialization makes it difficult to make historical generalizations as scholars observe that there are significant exceptions to any historical argument. Thus, professional historians tend to qualify their conclusions with such phrases as “research appears to suggest” or “based on this case study one might argue.” As the disruptive political campaign of 2016, with its considerable confusion over the roles of immigration, religious liberty, race, civil rights for all Americans, foreign policy, gun violence, terrorism, and foreign policy, demonstrated, all inhabitants of the United States need a better understanding of their national history, within an international context, that will provide a foundation for debate and civil discourse.

Talking American History is an attempt to address the crisis in American history by providing an informal narrative history of the United States from the Colonial period to the present day addressed to the intelligent general reader rather than the professional historian. History, while requiring the application of analytical tools, is fundamentally a story with many strands that interconnect over the course of time. This organizational structure of Talking American History is, therefore, rather traditional, employing a chronological approach centered around a rather old-fashioned political framework. However, the contributions of contemporary historians regarding the roles of race, gender, and class will be incorporated into the narrative. In the interest of full disclosure, it is reasonable to expect some information regarding the background and historical orientation of the storyteller.

I was raised in a poor white family with little in the way of education. My father dropped out of elementary school during the Great Depression. He was the hardest working person I have ever known, but his labors led him to an early grave rather than the elusive American dream. My mother was a high school graduate who raised two sons and entered the workforce as a bookkeeper. To earn additional money for essentials, the entire family worked, often alongside my grandparents, in the cotton fields of the Texas Panhandle. Chopping cotton, hoeing the weeds around the cotton plants, and picking cotton during the late summer and early fall were back-breaking labor that I have never forgotten. There were few books in the home, but for some reason I loved reading. Despite my enthusiasm for books, my grades were average at the best, and there was no consideration of college.

That assumption changed when I learned that student deferments were available as the draft allotments for the Vietnam War increased. Although my high school grades were rather shaky, I was accepted at the regional college, West Texas State University. My academic deficiencies were monitored by a young professor from Iowa, Dr. Peter Petersen, and I fell in love with a world of books and scholarship that I had never before experienced. The undergraduate years were difficult as, in addition to compensating for the gaps in my academic background, I had to support a young family on part time jobs and student loans. While Canyon, Texas was somewhat of a political backwater and hardly a bastion of leftist politics, I, nevertheless, identified with the protest movements opposing the Vietnam War, racial segregation, and economic inequality. I gravitated toward the small number of dissidents in the campus chapter of Students for a Democratic Society and identified with the counterculture, although my work and family responsibilities left little time for recreational drugs. Approaching the study of American history within this historical and cultural framework, I believed that I had discovered the reasons for my family’s poverty in the exploitive nature of American capitalism and politics under the sway of large corporations. While today I perceive such political and economic questions as more complex, I still find considerable truth within these youthful assumptions.

After earning undergraduate and master’s degrees in history from West Texas State University, I applied to a number of PhD programs—most of which were located in the Midwest. Although I was accepted to several doctoral programs, and came close to attending the University of Iowa, I selected the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque because it was number one in my pocketbook, offering me a tuition waiver and graduate assistantship in my first year of study. Perceiving $3,600 annually as a large salary, I enthusiastically embraced my studies under the guidance of Professor Gerald Nash, with whom I got along personally but disagreed regarding politics and interpretations of American history. For my dissertation subject I decided to focus upon four Midwestern progressive members of the Senate Farm Bloc during the 1920s, a topic which resonated with my own political orientation.

After completing my written and oral comprehensive examinations for the doctorate, along with preliminary research in the National Archives and Library of Congress, I found myself in somewhat of an economic crisis when my graduate assistantship expired. Accordingly, I decided to teach in the schools while writing my dissertation—an extremely difficult task with the expenditure of time required by teaching, researching, and writing. After two years at a Catholic junior high school with some classes approaching fifty students, in 1978 I accepted a position with an Albuquerque prep school, Sandia Preparatory School. With my educational background, I had no understanding of what an independent preparatory school entailed. Sandia Prep, however, was a small struggling institution and displayed none of the pretentious class consciousness of the stereotypical prep school. The school proved to be an excellent match for me, and I threw myself into the job which became more a way of life than an occupation as the school grew. In addition to teaching both middle and high school history classes, I served as a class sponsor, academic adviser, chaperoned dances and school trips, coached softball, established a Model United Nations program, and eventually ended up serving twenty-six years as the assistant head of school. Beyond these many duties at Sandia Prep, I taught history for twenty years at the University of New Mexico, Valencia campus.

These obligations, however, rendered it virtually impossible to complete my dissertation. After a number of busy years, I, nevertheless, again felt the urge to pursue historical scholarship, but I had lost interest in the Senate Farm Bloc. It finally occurred to me that engaging in historical writing and research from my primary location in the schools could be a liberating experience. I did not have to worry about attaining tenure and decided to pursue topics that would be of greater personal interest—although others would hopefully be motivated to read my work. Accordingly, I have completed seven books, along with numerous scholarly articles and encyclopedia pieces, on the popular culture topics of film, music, and sport—especially baseball—within historical and political context. The growth of Sandia Preparatory School also offered me an opportunity to develop and teach courses on American History Through Film and World Cinema. The school was also able to help with some travel funding that allowed me to share my research with colleagues at academic conferences. It occurred to me that perhaps it was possible to pursue a traditional academic career from a high school base. Although my teaching duties always came first, I was able to assume an active role within historical organizations such as the American Historical Association (AHA), Society for History Education (SHE), and Organization of American Historians (OAH), and I was fortunate to receive summer Fulbright study opportunities in the Netherlands, Japan, and Yugoslavia. During my forty-year teaching career, I was honored with teaching awards from the AHA, OAH, SHE, National Council for History Education, and the New Mexico Golden Apple. But the most important legacy of my teaching career is the continuing friendship of many former colleagues and students.

This rather lengthy background of my teaching and academic career does not mean that Talking American History is intended to be some type of teaching memoir or methods textbook. That is the topic for another book. Rather, Talking American History is an interpretative history, and it is only fair that the reader have some grasp of the author’s prejudices. Of course, readers should take some inventory of their own assumptions and preconceptions. Thus, it makes considerable difference from whose perspective the story is told. History is not unlike the same accident which eyewitnesses describe so differently. It matters from whose perspective events are viewed. For example, the topic of Western expansion is considerably sk...