- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Phytochemicals in Health and Disease

About this book

"? well-written and the content is clearly presented. ? There are plentiful figures and tables, which are effectively labeled and adequately support the content. ?highly recommended for academic and special libraries. ?effectively presents current research on phytochemicals in a readable manner."

- E-Streams

"This landmark volume shows h

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Phytochemicals in Health and Disease by Yongping Bao,Roger Fenwick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics1

Nutritional Genomics

Ruan M.Elliott, James R.Bacon, and Yongping Bao

Institute of Food Research, Colney, Norwich, United Kingdom

I. INTRODUCTION

It seems almost a given now that phytochemicals in our diet have health-promoting effects. The body of experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis (some of which is described elsewhere in this book) is substantial and continues to grow. However, many key questions remain. Which phytochemicals are the most efficacious? How do they work? Do they act independently or synergistically? How much should we consume, and in what form, to achieve optimal health benefits? How does this vary from person to person?

Until very recently, most of the research targeted at addressing these questions has had to focus upon single (or at most a few) genes, signaling pathways, or cellular processes and, most commonly, upon individual compounds. Over the last few years, molecular biological approaches, such as competitive and real-time RT-PCR and gene knockout models, have started to prove their worth in such studies [1–3]. These techniques are extremely valuable because they enable close scrutiny of possible modes of action. With sufficient such studies, it will be possible to begin to draw together the many different facets of the biological activities of phytochemicals to form a truly coherent view of how they work in vivo as agents present in real diets. But this goal is still some way off. The use of the new functional genomic approaches in nutrition research, so-called nutritional genomics, presents the possibility for an entirely new approach that seeks to develop a global view of the biological effects of food [4, 5]. This approach, in which the ultimate aim is to examine all genes and cellular pathways simultaneously in complex organisms, is sometimes termed systems biology.

If used sensibly, and in conjunction with the full range of nutrition research tools already available, nutritional genomics will significantly enhance the speed of movement towards a comprehensive understanding of how different phytochemicals promote health and how much we should aim to consume for maximum benefits. In conjunction with the rapidly developing knowledge of interindividual genetic variation, there is the very real opportunity to start to include in the overall process an assessment of the differences in dietary requirements for optimal health between individuals dependent on their age, gender, lifestyle, and genetic makeup.

Functional genomic techniques have another vital advantage over more traditional methods. They all enable the simultaneous examination of the regulation of many thousands of different cellular processes, meaning that unexpected effects are far less likely to be overlooked. This makes them ideal techniques for developing new hypotheses for mechanisms of action, for determining how different processes may interact together, and for identifying potential risks as well as defining the mechanisms that underlie health promotion. If this succeeds in reducing the number of health scares that result from dietary advice issued with an incomplete understanding of the full scope for beneficial and adverse biological effects, it can only be good for nutrition research, policy makers, and the general public. In this chapter, the fundamentals of the two current mainstays of functional genomic technology, DNA arrays and proteomics, will be detailed, together the complementary technology of real-time RT-PCR (TaqMan® assay). Developments in a third and newest key area of functional genomics, namely metabolomics, will also be described. Finally, the challenges that remain to be addressed will be discussed and some of the potential pitfalls that need to be recognized and avoided if the opportunities presented by these new technologies are to be fully realized will be highlighted.

II. TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS

Molecular biology and functional genomics, in particular, are jargon-rich disciplines. This can be daunting and confusing to those unfamiliar with the terminology. To assist the general reader and help avoid confusion, all the key terms used throughout this chapter are defined below:

A genome is the complete complement of nucleotide sequences, including structural genes, regulatory sequences, and noncoding DNA (or RNA) segments, in the chromosomes of an organism.

Genomics is, therefore, the study of all of the nucleotide sequences, including structural genes, regulatory sequences, and noncoding DNA segments, in the chromosomes of an organism. Genomics is sometimes divided into two separate components: structural and functional genomics.

Structural genomics is the DNA sequence analysis and construction of high-resolution genetic, physical, and transcript maps of an organism’s genes and genome.

Functional genomics is the application of global (genome-wide or system-wide) experimental approaches to assess gene function. Nutritional genomics is defined here as the application of all or any structural and functional genomic information/techniques within nutrition research.

A transcriptome is the complete complement of transcription products (i.e., RNA species) that can be produced by transcription of any components of an organism’s genome. In many cases one gene can give rise to multiple different transcripts through, for example, tissue-specific variations in transcription start sites and posttranscriptional processing. All such variants should be considered as part of the transcriptome.

Transcriptomics is the study of the transcriptome and its regulation. A proteome is the complete complement of translation products (i.e., polypeptides and proteins) that can be produced from the code held in an organism’s genome. As for a transcriptome, a full proteome will include protein variants produced from individual genes by alternative splicing of RNA transcripts and alternative posttranslational modifications.

Proteomics is the study of a proteome and its expression.

Metabolomics/Metabonomics is the application of systems-wide techniques (normally based on NMR) for metabolic profiling. Some scientists use the term “metabolomics” to describe such analyses in both simple (cellular) and complex (tissue or whole body) systems. Others distinguish between “metabolomics” studies in simple systems only (e.g., cell culture) and “metabonomics” studies performed in complex systems (e.g., the human body).

DNA arrays are analytical tools for measuring the relative levels of thousands or tens of thousands of RNA species within cellular or tissue samples. Use of DNA arrays is sometimes referred to as “transcriptomics,” although few if any current arrays for mammalian systems can truly be said to cover the entire transcriptome for the species being analysed.

Genotyping is the determination of interindividual variations in gene sequence.

Reverse transcriptio n polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is an experimental method for exponential amplification of a defined segment of complementary DNA (cDNA) produced by reverse transcription of RNA.

Real-time RT-PCR is a method based on RT-PCR for real-time detection of the products generated during each cycle of the PCR process, which are directly in proportion to the amount of template prior to the start of the PCR process.

There is an ongoing proliferation of’ “-omic” terminology in use in many different research areas (e.g., pharmacogenomics), reflecting the widely held view that the “allencompassing” approaches made possible by structural and functional genomic technologies have vast potential to advance research in nearly every aspect of the life sciences. However, in most cases the technologies used are essentially the same as those described here, and it is really only the application to the different research specialities that differs. Since these are not of direct relevance to this chapter, they will not be discussed further here.

III. REGULATION OF GENE EXPRESSION AND THE APPLICATION OF FUNCTIONAL GENOMICS

Gene expression is a multistep process for which many different possible modes of regulation have been recognized. It is this complexity that provides ample scope for the differential regulation of gene expression (e.g., developmental and tissue-specific switching on and off of defined genes) necessary for common precursor cells to differentiate into all the different cell types present in complex multicellular organisms, such as humans. Equally importantly, it enables each different cell type to respond in unique and defined ways to changes in their environment. Diet is a key factor that affects, both directly and indirectly, the environments to which cells in our tissues are exposed. As such, it should be no surprise that dietary components and their metabolites can have profound effects on gene expression patterns that will alter cellular function and ultimately impact upon health.

The gene expression process starts with transcription of a gene to produce RNA. If the RNA produced is a messenger RNA, it may then be translated into a protein. The protein product may be modified during or after synthesis, for example, by proteolytic cleavage, phosphorylation, or glycation. The amount of any given gene product and its activity (its level of expression) in a cell is determined by (1) the rate and efficiency of each of these processes, (2) the location of the product, and intermediates of its synthesis, within the cell, and (3) the rates at which the product and intermediates are degraded. Changes in each of these processes can potentially be detected using DNA microarrays, proteomics, and metabolomics. Other technologies, such as real-time RTPCR, complement these functional genomic techniques by providing more focused (i.e., small numbers of genes) but also more sensitive and accurate data to confirm and elaborate upon the broad spectrum data generated through functional genomic approaches.

A host of well-established molecular biological methods can be used to provide still more in-depth analysis; for example, determining whether an increase in the quantity of a specific RNA species is due to an increase in its rate of transcription or to a reduction in its rate of degradation. Descriptions of these approaches are beyond the scope of this chapter but can be found in many molecular biology texts (see, e.g., Ref. 6).

IV. TRANSCRIPTOMICS AND THE APPLICATION OF MACROAND MICROARRAYS

DNA arrays, like more traditional hybridization techniques such as Southern and Northern blotting, make use of the fact that single-stranded nucleic acid species (DNA and RNA) that possess sequences complementary to each other will hybridize together with exquisite specificity to form double-stranded complexes. In the traditional approaches, the samples to be analyzed are distributed according to size by gel electrophoresis, transferred to and immobilized on solid membrane supports, and probed with specific, labeled complementary nucleic acid sequences.

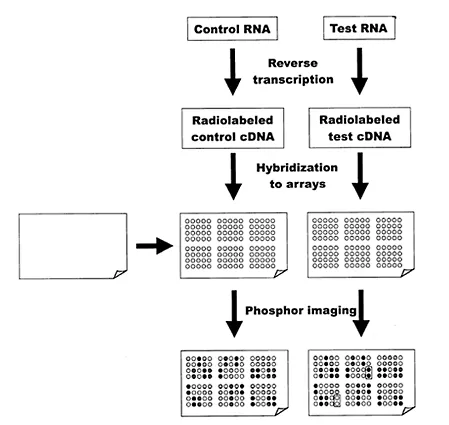

With DNA arrays, this approach is turned on its head [7]. Multiple, individual and known DNA species are arranged as spots (elements) in a grid (array) pattern on the solid substrate (Fig. 1). It is the test sample that is fluorescently or radioactively labeled and hybridized with the DNA on the solid support. Wherever nucleic acids present in the test sample encounter complementary sequences on the array, they will be captured. After washing away nonhybridized sample, the array can be imaged using appropriate techniques (phosphor imaging for radiolabeled samples or laser scanning for fluorescently labeled samples). The signal intensity returned from each element on the array is indicative of the relative abundance of the corresponding nucleic acid in the test sample.

Arrays can be employed for the analysis of both DNA and RNA samples. Analysis of genomic DNA samples has been used to determine whether specific genes are present or absent in, for example, DNA samples from different strains of yeast or bacteria. This technique (termed genomotyping) is proving very valuable in microbiological research. It is of little importance to human nutrition research, but the potential use of arrays to determine the genotype of an individual for many thousands of defined genes has very exciting potential.

By far the most widespread use of arrays to date has been with RNA samples for the analysis of gene expression at the level of transcription. It is this application that will be described here. Arrays are available in an ever-increasing number of different formats; currently, three predominate: membrane (macro)arrays, microarrays produced on specially coated glass microscope slides, and Affymetrix GeneChip® arrays.

A. Membrane Macroarrays

These are manufactured, using robotic systems, by spotting or spraying (using ink-jet technology) nucleic acid solutions (normally segments of genomic DNA or complementary DNA) onto nylon membranes to produce a defined grid (or array) with each spot corresponding to DNA from one gene (see Fig. 1). The spots of nucleic acids are denatured, if necessary, and fixed to the membrane, which is then ready for use. Due to their relatively large size, ranging in size from perhaps 5 to 25 cm along each side, membrane arrays are sometimes referred to as macroarrays.

Each array is hybridized with one test RNA sample. As with Northern and Southern blots, it is possible for the labeled sample to be stripped from the membrane after analysis so that the array can be reused. However, each time this process is performed there is some reduction in the performance of both the array and the quality of the data generated on subsequent use. Nutritional genomics 5

Figure 1 Membrane array analysis. DNA or oligonucleotides are printed onto nylon membranes and covalently bound. RNA samples are reverse transcribed and radiolabeled nucleotides incorporated into the cDNA products. Hybridization is performed under standard conditions. The arrays are washed and radioactivity detected by phosphorimaging. The patterns of spot intensities for control and test samples are compared to identify up-and downregulated transcripts.

The labeled “probe” for the array is cDNA produced from the test RNA sample by a reverse transcription reaction that includes one or more deoxynucleotide triphosphates radiolabeled with 32P or 33P in the alpha position. The reverse transcription process may be initiated by including either oligo dT or random hexamers to nonamers as the primer in the reaction mix; this use of random hexamers to nonamers is only appropriate when the PolyA-enriched RNA is used. Alternatively, a primer mix can be specially prepared that contains oligonucleotides with sequences complementary to portions of each of the RNAs represented on the array. This approach has the advantage that only RNAs of interest are reverse transcribed, thus giving stronger specific signals and lower backgrounds.

Following the reverse transcription reaction, the RNA is either degraded with RNase or hydrolyzed by alkali. The reverse transcribed, radiolabeled cDNA is purified using any one of a number of different commercial kits. Hybridization is performed using a standard hybridization buffer and a hybridization oven essentially as for any Northern or Southern blot [6]. Following a hybridization step, normally conducted overnight, unbound radiolabeled cDNA is removed using a series of high stringency washes. The amount of radiolabeled probe hybridized to each element on the array is determined by phosphor imaging. The pattern of the different signal intensities for each of the spots is indicative of the relative abundance of the RNA species in the original sample. Thus, each array analyzed provides a gene transcript profile for the sample analysed.

If a control RNA sample is analyzed on one array and a sample obtained following a specific treatment (such as treatment of cells in culture with a bioactive phytochemical) is analyzed on a second array, the gene transcript profiles can be compared. This approach is used to identify genes up- and downregulated at the level of transcriptio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series Introduction

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1: Nutritional Genomics

- 2: Methods to Study Bioavailability of Phytochemicals

- 3: Characterization of Polyphenol Metabolites

- 4: Microarray Profiling of Gene Expression Patterns of Genistein in Tumor Cells

- 5: Gene Regulatory Activity of Ginkgo biloba L.

- 6: Cancer Chemoprevention with Sulforaphane, a Dietary Isothiocyanate

- 7: Phytochemicals Protect Against Heterocyclic Amine-Induced DNA Adduct Formation

- 8: Organosulfur-Garlic Compounds and Cancer Prevention

- 9: Polymethylated Flavonoids: Cancer Preventive and Therapeutic Potentials Derived from Anti-inflammatory and Drug Metabollsm—Modifying Properties

- 10: Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Chemoprevention by Tea and Tea Polyphenols

- 11: The Role of Flavonoids in Protection Against Cataract

- 12: Phytochemicals and the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Potential Roles for Selected Fruits, Herbs, and Spices

- 13: Beneficial Effects of Resveratrol

- 14: The Role of Lycopene in Human Health

- 15: Effects of Oltipraz on Phase 1 and Phase 2 Xenobiotic-Metabolizlng Enzymes

- 16: Future Perspectives in Phytochemical and Health Research