- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using diaries, journals, and correspondences, Druett recounts the daily grind surgeons on nineteenth-century whaling ships faced: the rudimentary tools they used, the treatments they had at their disposal, the sorts of people they encountered in their travels, and the dangers they faced under the harsh conditions of life at sea.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rough Medicine by Joan Druett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Medicine at Sea: Woodall’s The Surgions Mate

It is no small presumption

to Dismember the Image of God.

John Woodall, 1617

AS LONG AS MEN AND WOMEN HAVE GONE TO SEA, DOCTORS HAVE accompanied them. Roman warships carried surgeons, as did vessels carrying princes and prelates in the Middle Ages. In 1588 William Clowes (1540–1604), an outstanding military surgeon of the sixteenth century, was in charge of the medical arrangements of the English fleet in their repulse of the Spanish Armada. The mighty Spanish fleet itself carried eighty-five surgeons and assistant surgeons. They were as helpless as Clowes was to stem the epidemic of dysentery and typhus that swept through the ships and decimated crews on both sides, but their presence is testament to the fact that it was standard practice to carry surgeons to sea in times of war. However, the man who can justifiably be called the father of sea surgery did not make his appearance until the early seventeenth century. This was John Woodall, a thoughtful and caring fellow who was the first surgeon-general of the East India Company.

Woodall, born about 1570, was apprenticed at about the age of sixteen to a London barber-surgeon. This indenture was supposed to last seven years, but Woodall was just nineteen when he joined Lord Willoughby’s regiment as surgeon—which was not unusual, since the prime qualification for surgery was the ability to stand the sight of blood. Willoughby had been dispatched by Queen Elizabeth to assist Henry IV of France in his campaign against the Catholic League in Normandy, so going to war ensured that young Woodall was exposed to revolutionary methods of treating battle wounds that had been developed by the famous French military surgeon, Ambroise Paré. Distinguished for his practical skills, Paré promoted the use of ligatures to prevent bleeding after amputation instead of cauterizing with pitch or boiling oil, as it had always been done before—a humane attitude that, as we shall see, characterized John Woodall too. Willoughby’s troops returned to England in 1590, but Woodall stayed on, lingering eight years in Europe. Finally back in London in 1599, he gained membership of the Company of Barber-Surgeons.

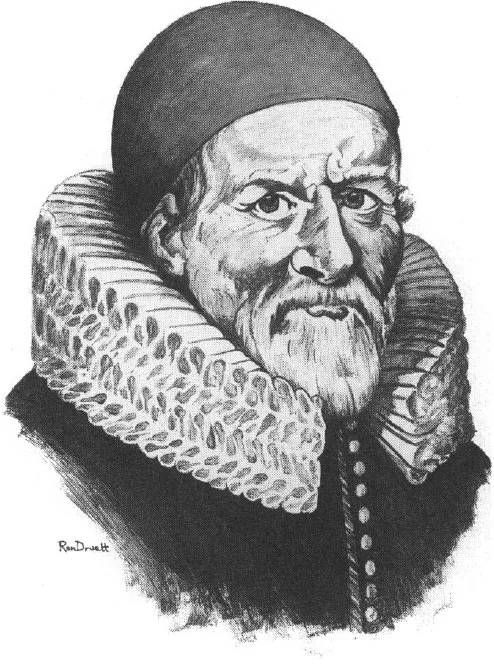

The Father of Sea Surgery. John Woodall (1569–1643).

ARTIST, RON DRUETT

Born in Warwick, the son of Richard and Mary Woodall, John Woodall was apprenticed to a barger-surgeon at the age of sixteen. Within three years he was serving in Europe as a military surgeon at the start of a brilliant medical career that included the publication of the first text in any language that was written specifically for surgeons at sea.

The title of Freeman of the Company of Barber-Surgeons, grand though it might sound, indicates that John Woodall was a practical tradesman and not an academic. Doctors’ credentials were much vaguer then than they are today, covering a whole range of medical treatment-related occupations, all of them overlapping and each with its own social status. At the top of the ladder was the physician, who was a university graduate in medicine or a Member of the Royal College of Physicians of London. Concerned with pure medical knowledge, he considered himself a gentleman and a scholar, and proved it with special dress and bearing. In the eighteenth century, for instance, he wore a distinctive wig and carried a gold-headed cane. As a physician, he prescribed medicine “physic”—but did not administer it. In fact, he might even prescribe without seeing the patient at all. A famous example of doctoring in this fashion was Queen Anne’s physician, Richard Mead (1673–1754), who was available for consultation at Tom’s Coffee House in Covent Garden, charging half a guinea for advice. After handing over the cash, an apothecary or surgeon would recite the symptoms he had observed in his patient. Then he would humbly wait while the lofty theorist meditated a little before writing out a prescription, the effectiveness of which went unchecked by a bedside visit.

This strange distancing of the physician from the patient dated back to Pope Innocent III and the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215. At that time, a code of behavior was drawn up which advised physicians to refrain from masturbation, intoxication, and extramarital intercourse (for any of these might endanger the soul of the patient), and prohibited them from practicing surgery even if the subject was dead, since the dismemberment of humans for study was forbidden. Physicians spent most of their time debating, writing, and preserving ancient dogma. Their role, if for instance a plague threatened, was to retire to a safe distance after writing out instructions for the guidance of the folk who were actually dealing with the sick. These caregivers were usually religious professionals such as nuns, rabbis, and monks, nursing the ill being an important part of their philanthropic and self-denying way of life. Earlier the clergy had been surgeons too, but after the 1215 Lateran Council passed an edict prohibiting priests from shedding blood, barber-surgeons performed all operations, though a priest-surgeon might shrive the patient and dress the wounds. That it was the barbers who took over the surgical role was probably due to the fact that the priests would have been used to seeing them at work when their whiskers were cut and their tonsures shaved, and, recognizing that they were clean by trade as well as accustomed to sharp tools, made use of them when it became necessary to pass on their knowledge of simple surgery along with techniques of letting blood. The earliest barber-surgeons would have worked under the supervision of priests, but as time went on, some became so adept and experienced that they took on apprentices themselves.

Today, the double role of the barber-surgeon is echoed in the red-striped pole that is still the barber’s traditional sign, symbolizing blood and bandages. The name of their guild—the Company of Barber-Surgeons—also advertised this union. Chartered in 1540, the organization was formed from an uneasy marriage of two groups—the career surgeons belonging to the Fellowship of Surgeons, who had had most of their training on the jousting ground and the battlefield, and the men who had been members of the Company of Barbers and owed their elevation in status to Pope Innocent III. The barbers, who had been given the official mandate to take over the profession when the monks were no longer allowed to take a knife to the human frame, considered themselves superior. The surgeons, being specialists, thought themselves the elite. Many of these specialists became itinerant, traveling about to offer their services at fairs and building up reputations in certain operations such as cataract removal (not easy in the days before anesthesia). This led to much patient-stealing and undercutting of fees, which inspired a great deal of resentment, especially when barbers who had agreed to confine themselves to barbering had to be disciplined by the company for displaying bowls of fresh gore in their store windows, thus signifying that they were prepared to be paid to let blood.

The barber-surgeons passed on their skills through an apprentice system, also inherited from the barbers’ guild. Letting blood, lancing boils, and extracting teeth were bread-and-butter skills, while amputation was the most common operation, along with sewing up abdominal wounds. They were prohibited from prescribing medicines, however, since this role belonged to the physicians. The rule was patently ridiculous, several Elizabethan surgeons pointing out the self-evident fact that as sea surgeons had to do their own prescribing (there being no physician on board to do it), it was only logical that the same should apply on land. Logical as the argument might have been, however, it did not prevail.

Barber-surgeons did not prepare medications, either (save upon the briny wave). In short, their sphere was confined to the razor, the saw, the needle, and the knife. On shore, the people who mixed the physic that the physicians prescribed were the apothecaries, who worked behind storefronts where pills, purges, and curvaceous bottles of colored fluids were displayed in bow-fronted, wavy-paned windows, usually accompanied by something mysterious and significant, such as a stuffed crocodile or a bust of Hippocrates. This, along with a large signboard that showed a pestle and mortar or apothecary’s scales, served to make them seem more like arcane alchemists than simple tradesmen. They gave free advice to people who purchased medicines too, even though physicians were the only practitioners officially mandated to do so.

In the beginning, the apothecary’s trade had been part of the realm of the importers and purveyors of spices and tobacco, who had been called “Pepperers” in the distant past but who, by Woodall’s time, were known as “Grocers”—or, more correctly, “Grossers,” because they dealt in bulk. The Grocers’ Company of London received its first Charter in 1428, and for a while was extremely powerful, being in control of the cleansing and sorting of spices and the regulation of heavy weights and measures, as well as the manufacture and sale of drugs and medicines. In 1617, however, the grocers’ importance in the field of medicine dwindled rapidly, for the apothecaries split away to form their own society.

As we shall see, that year of 1617 was important to John Woodall, too. Having gained his membership of the Barber-Surgeons’ company, he had returned to Europe, where he spent a year or so in the Netherlands working with a Dutch apothecary-alchemist, learning the elements of practical chemistry. Then he went back to London, where he treated victims of the 1603 plague epidemic. While there is no record of it, a tropical voyage must have followed, for Woodall demonstrated practical knowledge of medicine that could have only been acquired through such an experience. Such a journey must have been taken into account when in 1613 Sir Thomas Smith, the Governor of the East India Company, appointed him Surgeon-General.

Woodall’s duties as Surgeon-General of the East India Company were varied and strenuous, but at least he was given a place to live. “The Said Chirurgion and his Deputy shall have a place of lodging in the Yard,” ran the wording of the contract:

Where one of them shall give Attendance every working day from morning untill night, to cure any person or persons who may be hurt in the Service of this Company, and the like in all their Ships riding at an Anchor at Deptford and Blackwall, and at Erith, where hee shall also keepe a Deputy with his Chest furnished, to remaine there continually untill all the said ships be sayled down from thence to Gravesend.

Additionally, Woodall was in charge of “the ordering and appointing [of] fit and able Surgeons and Surgeon’s Mates for their ships and services, as also the fitting and furnishing of their Surgeons’ Chests with medicines instruments and other appurtenances thereto.” For this he was paid the grand sum of £30 per annum, reduced to £20 as a cost-cutting measure in 1628. Meantime, he was busily shipping surgeons who met his high standards of medical skill. A few grumpy ships’ captains accused him of hiring inferior characters and/or supplying defective medicines, but he easily fended off such scurrilous attacks.

Woodall held down the job for thirty years, despite other great responsibilities. In 1616 he was elected surgeon to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, thus becoming a colleague of Dr. William Harvey, the man who in 1628 first charted the circulation of the blood. He also rose through the highest echelons of the Barber-Surgeons company, attaining the status of examiner in 1626, warden in 1627, and master in 1633. Through his influence, the company was given the privilege of providing medical chests to both the navy and the army, for which they were paid by the Privy Council. This was personally supervised by Woodall. As he himself attested, he “had the whole ordering, making and appointing of His Highnesse Military provisions for Surgery, both for his Land and Sea-service,” in addition to his commitment to the East India Company to provide chests for their ships. This last was a responsibility that he retained until 1643, the year of his death.

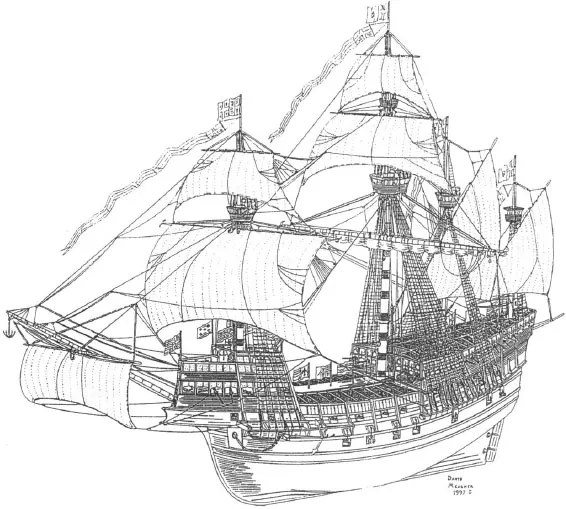

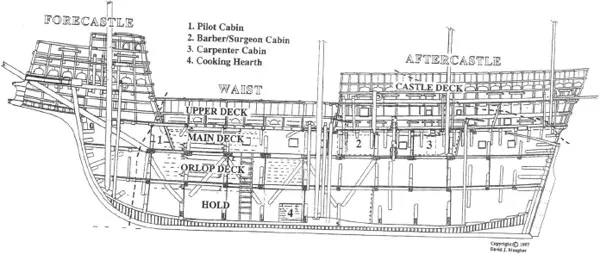

Mary Rose, 1545.

Two views, showing the Mary Rose under sail and a deck plan.

COURTESY DAVID MEAGHER

Named for the younger sister of Henry VIII, the flagship Mary Rose was one of England’s first men-of-war. She carried 200 sailors, 185 soldiers, and 30 gunners. Their health and fitness were the responsibility of Master Surgeon Robert Symp-son, whose mate was Henry Yonge. The surgeons’ operating room—like the galley where the food was cooked—was in the nethermost regions of the hold.

Woodall was also behind the passing of important and far-reaching bylaws, one protecting surgeons from being seized by naval press gangs without a prior permit from the company, and another requiring the company to give lectures in surgery and demonstrations in anatomy. As if this were not enough to take up all his energy and time, John Woodall also attended private patients, made speculative investments in the East India Company and Virginia, and invented the trephine, an advancement on the trepan, a tool for cutting away fractured pieces of skull and relieving pressure on the brain.

However, Woodall’s greatest achievement was the publication in 1617 of The Surgions Mate—the first textbook ever written in any language for surgeons at sea. It is impossible to tell how many copies there were of that first edition, because it was printed to order, to accompany the medical chests, but it must been an impressive number. Woodall declared that it was “Published chiefly for the benefit of young Sea-Surgions, imployed in the East-India Companies affaires,” but the book found its way into the cabins of hundreds of different kinds of ships. So many copies were lost at sea or in foreign ports that only eleven from the first printing are recorded in existence today. Another indication of its success is that it went on to three revisions, in 1639, 1653, and 1655, all equally popular.

WOODALL CLAIMED THAT HE PUBLISHED THE BOOK BECAUSE HE was “wearied with writing for every Shippe the same instructions a new.” And that is exactly what it is—an instruction book to accompany the contents of the medical chest, “with all the particulars thereof, into an order and method.” Methodical indeed, it is divided into four sections. First, there are lists of instruments and medicines, with notes about their use. Then comes a section describing wounds and other surgical emergencies, with detailed instructions for amputation, followed by a discussion of various medical problems. This includes a lengthy discourse on scurvy, the first ever published in English. The fourth section is devoted to alchemy, and contains treatises on sea salt, sulfur, and mercury. A glossary of chemical symbols and alchemist’s terms completes the book, some of it, rather startlingly, in lively verse, an echo of the poet-physician fad of the previous century.

In view of the harsh social setting of the time, the tone of the book is remarkably sympathetic. When Woodall gives precise instructions for the use of dental forceps, he wryly recounts two painful occasions when his own tooth shattered while being drawn, “which maketh me the more to comiserate others in that behalfe.” Where it was common practice to hack off broken or wounded limbs with merry abandon, Woodall instead advises his young surgeons to avoid amputation, “the most lamentable part of chirurgery,” wherever possible, for a doctor’s “over forwardnesse doth often as much hurt as good.” With rare understanding of the mental state of the patient, he also counsels the surgeon’s mate to spare as much emotional anguish as possible, first by consulting with the patient to make certain that the “worke bee done with his own free will,” and secondly by hiding “his sharpe instruments” from “the eyes of the patient” until the last possible moment.

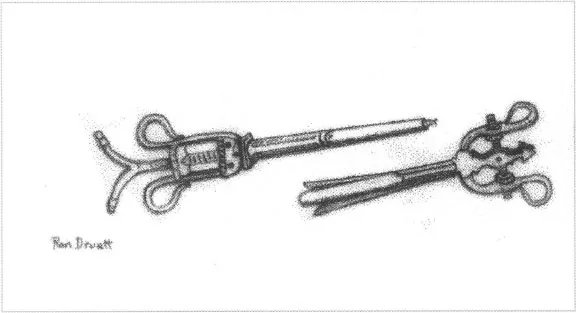

There were lots of these tools in Woodall’s arsenal—about seventy-five stowed in special compartments i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Medicine at Sea: Woodall’s The Surgions Mate

- 2. Shipping Out

- 3. The Medical Chest

- 4. The First Leg: Day-to-Day Life

- 5. The Whale Hunt

- 6. Accidents, Injuries, and Ailments

- 7. Battling Scurvy

- 8. Encounters with Native Peoples

- 9. “Motley, Reckless & Profligate”: Troubles with Captains and Crews

- Epilogue: The Fates of Our Surgeons

- Appendix A: Medical Chest Comparison

- Appendix B: Dr. King’s Patient List, Aurora, 1840

- Appendix C: Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index