- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

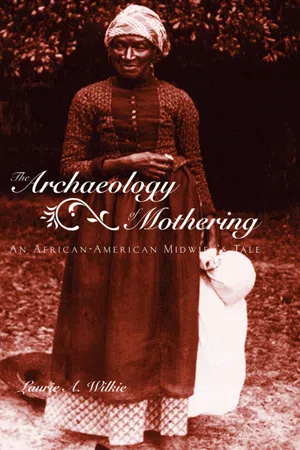

Using archaeological materials recovered from a housesite in Mobile, Alabama, Laurie Wilkie explores how one extended African-American family engaged with competing and conflicting mothering ideologies in the post-Emancipation South.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Archaeology of Mothering by Laurie A. Wilkie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Archéologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why an Archaeology of Mothering?

Introduction: What is it to Be a Mother?

For my five-year-old daughter, “family” is still a sacred trinity of “mommy,” “daddy,” and “baby.” It will not be long until her social contacts lead her to encounter other kinds of loving, nurturing families. With artificial insemination, DNA testing, surrogate mothers, remarriages, and adoption now common, and cloning seemingly on the horizon, the ways in which families become constructed will become more diverse. As the legal system attempts to sort out who is responsible for paying support for whom and who is a parent, contemporary society is forcefully confronted with the socially constructed nature of the role “parent” (Strathern 1992; Ragoné and Twine 2000; Chase and Rogers 2001).

While the notion that biology does not necessarily a parent make has become more acknowledged by the Western public, there is still a sense that what it is to act as a parent is more universal and essential—or natural. This is particularly true of women known as “mothers.” After Andrea Yates drowned her five children one by one in a bathtub, her lawyers offered in her defense that Yates, who clearly suffers from mental illness, must have been unaware of her actions, for no “loving mother” could do such a thing to her children. Such is the psychological power of the Western patriarchal ideology that asserts a women’s natural role is to reproduce and mother (Chodorow 1978). The nuclear family consisting of a working father, stay-at-home mother, and children of American society is so much a part of our hegemonic discourse that alternative realities and arrangements can be met with hostility (Gailey 2000; Dalton 2000).

Yet what it is to be a mother or to mother is as much a social construct as other cultural experiences, and as much a performative venture as other social identities. As such, what it is to mother well is constantly shifting and being renegotiated in private and public discourses (Glenn 1994). The ideologies that shape mothering are fluid, situated within changing social, economic, and political realities. Even the feelings that a mother nurtures for her children are socially constructed, routinized and performed. “Mother love,” or the natural affection that a woman is believed to hold for her child, is itself a social construction (Lewis 1997). Perhaps this has been most powerfully demonstrated in Nancy Scheper-Hughes’s (1992) exploration of what she refers to as “M(Other)” love in the Alto do Cruzeiro of Brazil. Here, mother love was an expensive luxury that could cost a mother all, instead of a few, of her children. Economic conditions were so dire in the area that, Scheper-Hughes found, mothers had to form a protective detachment from their infants and children so that they could endure the death of children. This detachment was so extreme as to allow women to choose infants they determined most likely to be healthy, and to severely neglect those believed destined to die. Placed in dire circumstances, women had to channel their emotions for their children pragmatically. Mary Picone (1998) has observed similar situations in Japan, where infanticide was still practiced with great regularity through the Second World War. Economic circumstances and lack of reliable birth control also led to high rates of abortion. Coexisting with the great demand for abortion were the mizugo cults, directed at appeasing the spirits of aborted fetuses.

Parenting, but particularly mothering, becomes the focus of cultural tensions and communal discourse because of the central importance of successful child rearing in any society. Children are a form of natural resource whose successful transformation to adulthood ensures a society’s continuation. Childhood “is a primary nexus of mediation between public norms and private life” (Scheper-Hughes and Sargent 1998b:1), and caregivers cannot be separated from those debates. Mothering, then, is both a private and public endeavor, with individuals involved in mothering conscious of multiple scales of responsibility—to her children, her kin, and her broader community (Ruddick 1980).

Research into mothering, how children are nurtured, and motherhood as a socially constituted and negotiated institution have been main themes in feminist thinking. Many women have the experience of mothering; it brings with it differing losses and gains in status, joy, heartbreak, and ambivalence, and for birthgivers it brings a transformative embodied experience. Feminists have explored motherhood from multiple angles and perspectives. One important ongoing site of debate has been whether it is biologically ordained that women should be children’s primary caretakers (e.g., Ortner 1972; Chodorow 1978; Abel and Nelson 1990; Holloway and Featherstone 1997; MacCormack and Strathern 1980). Another has focused on the ways maternity is used to oppress women cross-culturally (e.g., Rosaldo and Lamphere 1974; Rich 1976; Bassin and Kaplan 1994). In these analyses, it is motherhood as an institution that is the focus of consideration, as well as the ways that women unwittingly reproduce the institution that devalues them. Indeed, feminists have been unable to agree on whether motherhood is a good or bad for women, though collectively they do resist the paradigm of “essential mothering,” which posits that womanhood is defined by the ability to reproduce and raise children (DiQuinzio 1999).

In much of Western society, a normative view of mothering demands self-sacrifice and total attention be paid to children by their mothers. Behavioral and social problems that arise later in a child’s life can ultimately be traced to experiences of inferior mothering (Chase and Rogers 2001; Ladd-Taylor and Umansky 1998). Picone (1998:51) observed that poor mothering was used in Japan to explain the behavior of rapists and murderous pedophiles. This is a society where a mere 100 years prior a Japanese moralist proclaimed, “Women were such imperfect beings that mothers should not be in contact with impressionable children” (Picone 1998:50).

“Intensive mothering,” as it has been termed by Sharon Hays (1996), is rooted in the rise of industrialism and the separation of the household unit from a role in production among the predominantly white middle classes. Women’s labor increasingly became associated with the protection of the household, and control of wealth and the family’s symbolic capital became the domain of male workers. Women who worked outside of the home, either out of financial need or for selffulfillment, were automatically constructed as “bad mothers.” The hegemonic discourse surrounding the “cult of true womanhood” excluded many women, and they continued to be excluded by feminist movements, which privileged the experiences of sexism by white middle-class women (Spelman 1988; Collins 1994). In the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century United States, the cult of true womanhood led women to be equated with their reproductive organs. Proclaimed to be interested only in (and good only for) bearing and raising children, women became the butt of fierce arguments by male pundits that they should not be educated. The energy used to fuel the intellect, it seems, was drained from the womb and ovaries, rendering educated women infertile and prone to mental diseases (Bullough and Voght 1984).

It was in part the entrenched notion of the “unthinking” mother that led Sara Ruddick (1980, 1994) to theorize mothering, and in particular, “maternal thought” as a community-oriented way of being that characterized mothers’ cultural participation. But what is it to mother? Ruddick (1994:33) perceives mothering as a form of caring work that exists in response to the needs of children. To see a child’s need for protection is to mother. “There is nothing inevitable about maternal response: many people, including some birthgivers, do not recognize children as ‘demanding’; some, including some birthgivers, respond to children’s demands with indifference, assault, or active neglect; some, including many birthgivers, are unable to respond because they themselves are victims of violence or neglect.” Ruddick’s work on maternal thinking has been influential in the field, but it has also been used to illustrate that feminism continues to take as its focus the experiences of white middle-class women (A. Davis 1983; Giddings 1984; Spelman 1988; Collins 2000). Spelman (1988:15) has observed, “One’s gender identity is not related to one’s racial and class identity as the parts of pop-bead necklaces are related, separable and insertable in other ‘strands’ with different racial and class ‘parts’”—in other words, it is misguided to conceive of a universal woman’s experience.

Collins (1994, 2000) has called for feminists to consider the full diversity of women’s mothering experiences, and to recognize that

women of color have performed motherwork that challenges social constructions of work and family as separate spheres, of male and female gender roles as similarly dichotomized, and of the search for autonomy as the guiding human question . . . ‘motherwork’ goes beyond ensuring the survival of one’s own biological children or those of one’s family. This type of motherwork recognizes that individual survival, empowerment, and identity require group survival empowerment, and identity. (1994:47)

It is through the exploration of difference that we can begin to understand how social constructions of motherhood create divergent opportunities and experiences of women of differing sexual orientations, races, ethnicities and socioeconomic classes. Recent work focusing on difference in mothering experience (e.g. Glenn et al. 1994; Scheper-Hughes and Sargent 1998b; Ladd-Taylor and Umansky 1998; Ragoné and Twine 2000; Strathern 1992) has demonstrated the rich potential for this research. It is the work of these feminists that has most influenced this archaeology of mothering, and I join Maria Franklin (2001) in recognizing the need for historical archaeologists to incorporate black feminist perspectives into our research.

Archaeology is, in many ways, a brilliant forum in which to explore mothering and motherwork. Ideologies regarding normative expectations for childrearing and nurturing are likely to be reified through a number of material media, such as ritual performance, public art, or household goods. The performative practice of parenting would be part of a routinized experience and extractable from household contexts. Although material culture has not been the focus of most studies of mothering, I will quickly refer to several that suggest the great potential that exists in this area. Ruth Schwartz Cowan (1983) in her study of household gadgets, has demonstrated how money-saving devices designed to lighten the workloads of full-time homemakers and mothers actually increased the amount of time necessary to conduct housework. More recently, Linda Layne (2000) has written about the ways that grieving parents use a baby’s belongings to comfort themselves following a miscarriage, stillbirth, or infant’s death. Rima Apple’s (1997) study of scientific mothering was drawn, in part, from a study of advertising cards. Archaeology contains great potential for understanding the experiences of caregivers and parents, and particularly motherhood as it has been constructed in the recent past.

Mothering and Archaeology

Surely, the discipline of archaeology, with recent research focusing on women, children, gender, sex, and sexuality (e.g., Gero and Conkey 1991; Gilchrist 1994, 1999; Joyce 2000; Meskell 1999; Schmidt and Voss 2000; Sofaer-Derevenski 2000) has mothering and motherhood covered under its ever-widening postprocessual umbrella? Do we really need an archaeology of something else? One would think that mothering, certainly a socially constructed and gendered activity cross-culturally, with its definite sexual and reproductive dimensions and associations with children, would be a focus within one of the numerous recently edited volumes associated with these topics. That in fact is not the case, however. In established texts relating to gender and archaeology (e.g., Gero and Conkey 1991; Wright 1996; Seifert 1991; Nelson 1997), women produce pottery, textiles, and lithics, they pound acorns, and they commune with awls. Mothering is generally absent, unless you include mother goddesses.

The term “mother” is not even commonly found in the indices of texts on gender in archaeology. To demonstrate how obscure the term is, neither Roberta Gilchrist’s recent and seemingly comprehensive text Gender and Archaeology (1999) nor Joanna Sofaer-Derevenski’s edited volume Children and Material Culture (2000) include it. I should also add, quickly, that I am throwing stones at myself here as well. When putting together the index for my previous book (Wilkie 2000a), which focuses on intergenerational dynamics in several households, including mother-child relationships, I never considered that someone might want to look up the topic of “mother” or “mothering” in my index. Nor did I explicitly explore mothering and motherhood in the study.

The absence of mothering from archaeological discourse is surprising. Archaeologies of gender and sexuality are becoming more common in the field, although they still lag behind such popular topics as warfare, subsistence, political and economic systems, and cannibalism. Much of gendered archaeology comes from second- or third-wave feminist theorizing, but somehow archaeology has not yet embraced the feminist histories, sociologies, and anthropologies related to mothering. A number of important feminist studies have explored motherhood since the late 1970s (e.g., Rich 1976; Chodorow 1978; Ruddick 1980; Ryan 1981; Scheper-Hughes 1992; Glenn et al. 1994), and in the last five years or so we have seen a burgeoning publication base dealing with motherhood in the social sciences (e.g., Ladd-Taylor and Umansky 1998; DiQuinzio 1999; Ragoné and Twine 2000; Chase and Rogers 2001). Archaeology has been notoriously slow in keeping up with theoretical and topical trends shaping other disciplines, so perhaps our time lag here is not as surprising as it seems to me. Particularly within historical archaeology, however, theoretical orientations that favor a focus on capitalism, consumerism, and consumption over family, gender, and social networks seem to have led to the squelching of issues related to mothering and motherhood.

I do not wish to give the impression that the archaeological literature is completely lacking in research that addresses aspects of motherhood or mothering. In part, parenting can be inferred from recent studies focusing on children (e.g., Sofaer-Derevenski 1994, 2000). The topic can also be gleaned from works on other topics. Elisabeth Beausang has recently published an article on the mechanics of becoming a mother (childbirth) in prehistory. In this piece, Beausang (2000:73–74) considers mothering to be a constituted as both norms (cultural expectations) and praxis. She focuses her attention predominantly on mothering that takes place during a child’s infancy, since at this time the child is most likely to be dependent upon a female for its nurturing, thus justifying the gender implications of a term like “mothering.” Lynn Meskell has written about birthing beds in ancient Egypt (2000), and Rosemary Joyce (2000) has discussed childbirth in Mesoamerica as a female complement to the male experience of warfare. Though none of these works deal explicitly with what happens after the transformative experience of birth, that they deal with birth at all is noteworthy.

Perhaps more surprising than the dearth of prehistoric archaeology dealing with mothers and mothering (or to be gender neutral, nurturing) is the same lack of attention the subject receives in American historical or post-medieval archaeologies. Archaeologists who work in recent time periods routinely work at the household level and often have access to documents that define the biological and fictive kinship relationships between members of a household. The muchutilized Federal Population Census in the United States is an excellent example of such a resource. Not only can archaeologists in these circumstances potentially identify specific persons who may have lived at particular sites, but we may also be able to pinpoint deposits to specific times in those persons’ lives. At a time when issues of identity and difference are of such interest in archaeology (e.g., Meskell 1999; Joyce 2000; Hodder et al. 1995; S. Jones 1997; Orser 2001a; Delle, Mrozowski, and Paynter 2000), it is surprising that archaeologies of the recent past have not explored more extensively the changes of status and practice that came with marriage and mothering. What publications have dealt explicitly with mothering and motherhood are scant and deserve a brief review.

A published essay by Ywone Edwards-Ingram (2001) and her forthcoming dissertation, which focuses on African-American medical practices during enslavement, are the only other work in historical archaeology of which I am aware to explicitly consider how mothers and mothering were affected by slavery. Edwards-Ingram’s study provides an overview of medicinal practices related to reproduction and childrearing, synthesizing ethnohistoric and archaeological data drawn from the American South and the Caribbean. Her study provides insights into the ways that enslaved mothers contested the constraints on their mothering and how they worked to incorporate African healing traditions into their children’s lives.

The other explicit study of mothering I have found in historical archaeology was published in 1994 in an article by Eric Larsen called “A Boarding House Madonna: Beyond the Aesthetics of a Portrait Created through Medicine Bottles.” Drawing upon four bottles—a nursing bottle, a bottle for a whooping cough cure, and two castoria bottles—recovered from a nineteenth-century Harper’s Ferry boarding house, Larsen suggested that the medicines could be associated with “good mothering” practices of the period. The article is unusual in that Larsen attempts to distinguish, although not explicitly, between the dominant ideology governing motherhood versus the practice of mothering found in the boarding house. This piece stands alone as an attempt at an archaeology of mothering. Ultimately, the article could have been strengthened by greater attention to the positioning of working-class women relative to the cult of true womanhood. That said, it is a remarkable contribution.

Diane DiZerga Wall (1991, 1994, 2000) can be credited with bringing the first detailed attention in historical archaeology to the separation of the domestic and industrial spheres of daily life in American society. Though Wall discusses, briefly, the effects of the development of the domestic sphere on child-rearing practices, the focus of her archaeological analysis lies elsewhere—mainly on the strategies employed by middle-class homemakers to jockey for social prestige among themselves through entertaining.

Rebecca Claney (1996) offers a provocative analysis that interprets the ubiquitous “Rebecca at the Well” teapot of mid-nineteenth-century American society to be a material reification of the cult of true womanhood and values of motherhood. Fitts (1999), in a discussion of gentility and Victorian values, notes the importance of child rearing to maintaining class status across generational lines, a point also found in Praetzellis and Praetzellis (1992).

In her study of prostitution, Julia Costello (2000) makes brief mention of mothering in the sex industry. Costello uses multiple first-person oral history narratives from a New Orleans red-light district, Storyville, juxtaposed with historical photographs and artifact illustrations to present a possible view of life inside an early-twentieth-century Los Angeles bordello and to bring the possible meanings of artifacts found there to the fore. In the text is one photograph that illustrates several medical appliances recovered from the site, including a glass breast pump. Costello includes a narrative from the perspective of two adults who had been born to prostitutes. The narrative is brusque and unapologetic. While both individuals refer to the reality of prostitutes getting pregnant, neither refers to what it was like to be raised or mothered in that context. Apart from the photograph of the breast pump, the article gives few clues as to what other artifacts might have been recovered related to mothering or child care. Costello shied away from engaging more politically charged issues, such as what kind of mothers the prostitutes were, whether their mothering challenged or reified socially held notions of motherhood at the time, and, most controversially, what they did to avoid motherhood. While the subject of her text was sexuality as studied through archaeology, her decision to keep separate the personas of “woman the sexual object” and “woman the mother” mimics the Victorian attitudes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1. Why an Archaeology of Mothering?

- 2. The Perryman Family of Mobile

- 3. African-American Mothering and Enslavement

- 4. Mothering and Domesticity in Freedom: Ideology and Practice

- 5. Midwifery as Mother’s Work

- 6. To Mother or Not to Mother

- 7. Midwifery and Scientific Mothering

- 8. Conclusions: The Many Ideologies of African-American Motherhood

- Bibliography

- Index