- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Molecular Signaling in Spermatogenesis and Male Infertility

About this book

Spermatogenesis involves the coordination of a number of signaling pathways, which culminate into production of sperm. Its failure results in male factor infertility, which can be due to hormonal, environmental, genetic or other unknown factors. This book includes chapters on most of the signaling pathways known to contribute to spermatogenesis. Latest research in germ cell signaling like the role of small RNAs in spermatogenesis is also discussed. This book aims to serve as a reference for both clinicians and researchers, explaining possible causes of infertility and exploring various treatment methods for management through the basic understanding of the role of molecular signaling.

Key Features

- Discusses the signaling pathways that contribute to successful

spermatogenesis - Covers comprehensive information about Spermatogenesis at

one place - Explores the vital aspects of male fertility and infertility

- Explains the epigenetic regulation of germ cell development

and fertility - Highlights the translational opportunities in molecular signaling

in testis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Molecular Signaling in Spermatogenesis and Male Infertility by Rajender Singh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Medicina di famiglia e medicina generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Primordial germ cells: Origin, migration and testicular development

Saumya Sarkar and Rajender Singh

1.1Introduction

1.2Origin of primordial germ cells

1.2.1Molecular mechanisms during the origin of PGCs

1.3Migration of PGCs

1.3.1Molecular mechanisms during PGC migration

1.3.2Migration stoppage of PGCs

1.4Gonad and testicular development

1.4.1Sertoli cell specification and expansion

1.4.2Testis cord formation and compartmentalization

1.4.3Formation of seminiferous tubules from testis cord by elongation

1.5Conclusion and future directions

Acknowledgments

References

HIGHLIGHTS

•Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are predecessors of sperm and oocytes, which undergo complex developmental process to give rise to the upcoming generations.

•Germ cell–specific genes and many other proteins, like BMP and SMAD, are responsible for the proper growth of PGCs.

•After specification, germ cells enter the migratory phase where they relocate themselves to constitute the gonadal ridge.

•This migration phase is crucial for the PGC development where various pathways, mechanisms and proteins exert their actions.

•The gonadal ridge undergoes extensive morphological and molecular developmental changes, where it attains its ability to produce and nurse the germ cells.

1.1 Introduction

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are the precursors of sperm and ova, which are specified during early mammalian postimplantation development. These entities have the full potential to generate an entirely new organism by undergoing specific genetic, epigenetic and molecular programming. Studies on the PGC development revealed surprising control and regulation patterns in the process of migration, which are conserved across many species. The testis and ovary arise from a common primordial structure but are functionally analogous in nature. Very specific programs of gene regulation and cellular organization drive the development of the genital ridge into the testis.

1.2 Origin of primordial germ cells

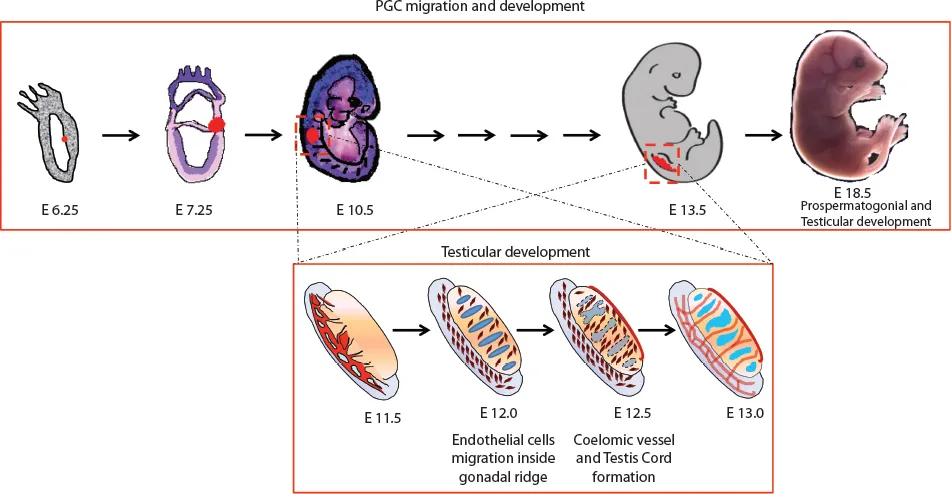

During development at the early gastrulation stage, a scanty population of pluripotent epiblast cells “set aside” to become spermatozoa and oocytes are described as the primordial germ cells (PGCs) (Figure 1.1). These PGCs originate from pregastrulation postimplantation embryos and play a uniquely important role of transmission (after meiotic recombination) of genetic information from one generation to the next in every sexually reproducing animal and plant. The production of sperm and ova by the process of spermatogenesis and oogenesis, respectively, has been intensively studied by the reproductive biologist in various species of both vertebrates and invertebrates. In 1954, Duncan Chiquoine identified PGCs for the first time in mammals by their high alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity and capability of generating both oocytes and spermatozoa (1). He found these cells at the base of the emerging allantois in the endoderm of the yolk sac of mouse embryos at E7.25 immediately below the primitive streak. However, the origin of human PGCs (hPGCs) was less well studied because of the ethical and technical obstacles. Recent studies by simulation in vitro models using human pluripotent stem cells with nonrodent mammalian embryos have given us the first ever insights on the probable origin of hPGCs, suggesting the posterior epiblast in pregastulation embryos as the source (2). The investigations on the presence of AP across different studies have observed different origin sites for the PGCs, for example, the posterior primitive streak (2–4), the yolk sac endoderm (2) and the extraembryonic allantoic mesoderm (5). However, it was suggested that allantoic tissue cannot give rise to embryonic body tissues, including the germ cells at the E7.25 stage (6). A study using transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under a truncated Oct4 promoter visualized living PGCs as a dispersed population in the posterior end of the primitive streak (7).

Figure 1.1 The timeline of the PGC origin, migration and gonad formation. The gonadal ridge transforms itself into male testis until the E13.0 stage, where Sertoli cell differentiation along with testis cord formation takes place.

1.2.1 Molecular mechanisms during the origin of PGCs

Speciation of the PGCs requires specific molecular changes, and to understand these, a few studies have suggested a method to identify key determining factors for germ cell fate. The embryonic region containing the founder germ cells shows a difference in the expression of two germ cell–specific genes, Fragilis and Stella. The expression pattern of Stella is restricted to those cells that are going to be PGC with the universal expression of Fragilis. Therefore, both genes appear to play important roles in germ cell development and differentiation (8). Bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) also play a vital didactic role in PGC speciation and formation at the time of their origin. BMP2, BMP4 and BMP8B are the players that act through SMAD1 and SMAD 2 signaling. This provocative nature of BMPs is well studied. It is suggested that the response of the epiblast cells to PGC specification is dose dependent in nature in vivo, as BMP2 and BMP4 alleles decrease, the proportion of PGC also goes down (9). Whereas, in vitro, only BMP4 is required for PGC induction, along with WNT3, which is required to induce competence for PGC fate and proper cross talk to BMP signaling for PGC specification (10). Every cell of postimplantation epiblast at this stage is capable of becoming a PGC, but it is only due to selective gradients of BMP signaling and inhibitory signals of Cerberus 1 (CER1), dickkopf 1 (DKK1) and LEFTY1 from distal and anterior visceral endoderm that a few attain PGC fate (10,11). Along with developmental pluripotency-associated 3 [Dppa3 (previously Stella) BLIMP1, a positive regulatory (PR) domain zinc-finger protein product of Prdm1 acts as a key regulator of PGC specification (12–15). BLIMP1 expression in the proximal epiblast cells at ∼E6.25 marks the onset of the PGC specification (16). BLIMP1 represses the incipient mesodermal program, which distinguishes germ cells from the neighboring somatic cells (13,14,17). Mutations in BLIMP1 and Prdm14 resulted in aberrant PGC-like cells at ∼E8.5 and ∼E11.5, respec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Editor

- Contributors

- 1. Primordial germ cells: Origin, migration and testicular development

- 2. DNA methylation, imprinting and gene regulation in germ cells

- 3. Testicular stem cells, spermatogenesis and infertility

- 4. Testicular germ cell apoptosis and spermatogenesis

- 5. Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis

- 6. GH–IGF1 axis in spermatogenesis and male fertility

- 7. Retinoic acid signaling in spermatogenesis and male (in)fertility

- 8. Testosterone signaling in spermatogenesis, male fertility and infertility

- 9. Wnt signaling in spermatogenesis and male infertility

- 10. MAPK signaling in spermatogenesis and male infertility

- 11. TGF-β signaling in testicular development, spermatogenesis, and infertility

- 12. Notch signaling in spermatogenesis and male (in)fertility

- 13. Hedgehog signaling in spermatogenesis and male fertility

- 14. mTOR signaling in spermatogenesis and male infertility

- 15. JAK-STAT pathway: Testicular development, spermatogenesis and fertility

- 16. PI3K signaling in spermatogenesis and male infertility

- 17. Spermatogenesis, heat stress and male infertility

- Index