- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

There has been surprisingly little writing about the condition of contemporary tribal government. Library shelves are filled with works on other American and foreign governments, but an inquirer must leam about tribal government incidentally and in piecemeal fashion. This state of scholarship is regrettable because of the importance of the modem I

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tribal Government Today by James J Lopach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Contours of Reservation Politics

A century and a half ago the area which is now Montana was part of the homeland of the great Indian tribes of the northern plains. From the Rocky Mountains to the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri and from Canada to the Little Bighorn, Native American peoples carried out the independent and ordered lives of sovereign nations. Today, following military conquest and colonial rule, these tribes are striving to reestablish self-government and to regain economic self-sufficiency on the fragments of land they have preserved from deception and betrayal. This study deals with these two central themes of contemporary tribal politics. Its focus is the workings and results of tribal government on Montana's seven dissimilar Indian reservations.

Ten tribes live on Montana's reservations. Their pasts differ in many ways. Native territories included the Great Lakes and Pacific Northwest as well as the upper Midwest. Not all were initially hunters. Some fished, some were agriculturalists, and some trapped for furs. The tribes reacted to whites in different ways. Some were hostile, while others earned a reputation of hospitality. In their intertribal relationships, the Montana Indians showed a similar variety of behavior. Some tribes were allies but most engaged in warfare, even against those with whom they would be induced to share a reservation years later. Different views of life included a respect for nature and a disposition to exploit for immediate gain, an openness to new ways and refuge in the past fueled by suspicion of the present. Brief sketches of the ten tribes—and chapter-length treatment below—will highlight some of these differences.

The Indians of the Flathead reservation are principally the Salish and the Kootenai. They were Plateau Indians, living in the Pacific Northwest between the Cascades and the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. The Salish (or Flatheads) were exceptionally sociable and borrowed heavily from the culture of the Plains Indians. They inhabited the buffalo range of the Upper Missouri until Blackfeet warriors and smallpox in the late eighteenth century drove them across the mountains into the Bitterroot Valley. The Kootenai, from the upper Columbia drainage, were not as friendly to outsiders and receptive to new ways as the Salish and came to represent a conservative influence on the Flathead reservation. Their shared reservation home would ultimately be located in the Jocko and Mission Valleys, about seventy-five miles from the Bitterroot Valley.

The Blackfeet nation was a proud, independent, and aggressive people who dominated a territory which extended from the Judith Basin north into Canada and from the Musselshell River west to the Rocky Mountains. Their life was centered on the buffalo hunt, and they fiercely protected this resource from intruders. Eventually the Blackfeet reservation occupied only the northwestern corner of the tribe's vast homeland.

The tribal territory of the Crow Indians was the country of the Upper Missouri, the Yellowstone, and the Bighorn. The Crow were hunters and perpetual enemies of the Blackfeet, Cheyenne, and Sioux. Toward whites, however, they generally were friendly, and they had the almost unique reputation of being humanitarian in their conduct of war with other tribes. The Crow reservation today lies at the center of the tribe's former homeland.

The Cheyenne originated in the Great Lakes region of northern Minnesota and supported themselves by planting and fishing, becoming hunters only after they were driven westward by the Cree, Assiniboine, and Sioux. In the 1830s the Cheyenne split into southern and northern bands. The Northern Cheyenne in 1884 came to the Tongue River in Montana after an arduous 1,500 mile journey out of a southern exile. This hill country was declared the Northern Cheyennes' reservation in the late nineteenth century.

The Assiniboines' history is linked closely with the Sioux. The two tribes separated in Minnesota in the seventeenth century and became distinct peoples. In the early nineteenth century the Assiniboine moved into the country of the Upper Missouri and for a time dominated that region as hunters and warriors. Weakened by smallpox fifty years later, the Assiniboine were able to preserve only a small hunting ground from the onslaughts of the Blackfeet, Crow, and Sioux. The Assiniboines' two reservations in Montana are shared with the Sioux and the Gros Ventres.

The early homeland of the Sioux was extremely large, including parts of Minnesota, the Dakotas, Wyoming, Nebraska, and eastern Montana. The Sioux were numerous and had the reputation of being uncompromising in battle. In their government the Sioux were tightly organized and severely regulated. These qualities caused them to be both feared and respected. The Fort Peck reservation of the Montana Sioux, which is shared by the Assiniboine, occupies the northeastern corner of the state and traces its lineage to survivors of Custer's Last Stand.

Studies of the Gros Ventre Indians trace their roots variously to the Crow and Arapaho tribes. The Gros Ventre also had a long association with the Blackfeet, dwelling with them and adopting their language for some purposes. The westward movement of the Gros Ventre first stopped at the Milk River and later ended further south near the Missouri. Frequent fighting with the Assiniboine and Crow was necessary to protect their hunting territory. The reservation home of the Gros Ventre at Fort Belknap is along the Milk River and is shared with the Assiniboine.

The Chippewa and Cree were Great Lakes tribes and of common ancestry. The Cree were Canadian Indians who in their trek westward evolved from woodlands trappers to buffalo hunters. The Chippewas' home was south of Lake Superior where they supported themselves by fishing and planting. Some of the Chippewa who migrated westward linked up with bands of Cree. Both tribes were excluded from the reservation movement of the late nineteenth century, and in the early 1900s in Montana they lived in poverty on the outskirts of white communities. Establishment of the Rocky Boy's reservation in 1916 was more to ease the state's conscience than to create a homeland capable of subsistence.

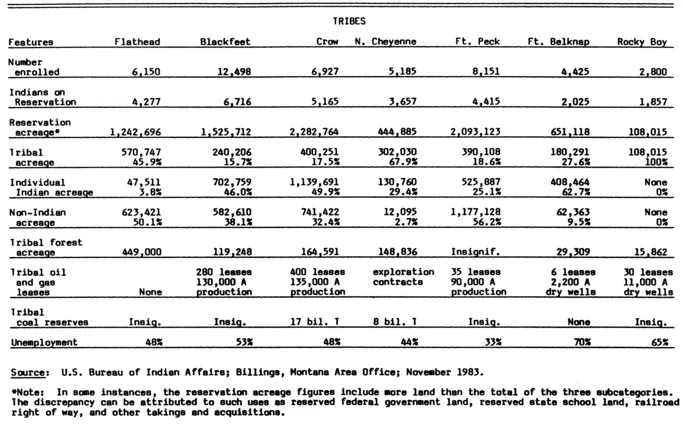

The seven Indian reservations in Montana are not any more identical than are the ten tribes that dwell there. Together these reservations occupy 8.3 million acres, which is 9 percent of Montana's land area. The reservation Indian population of just over 28,000 is under 5 percent of the state's residents. The significance of reservation features, however, lies far more in intertribal comparisons than in collective proportionality to the State of Montana. Table 1.1 supports several judgments about some critical differences between the reservations.

The Montana reservations vary considerably in geographical size, Indian population, tribal land holdings, white presence, natural resource wealth, and unemployment. The acreage of the Crow reservation, for example, is larger than Rocky Boy's by a factor of twenty, and the Blackfeet Indian population is more than three times that of Fort Belknap. On the Northern Cheyenne reservation only 3 percent of the acreage is owned by non-Indians, while whites hold title to 32 percent of the land within the adjacent Crow reservation. The Flathead reservation has great income potential from timber, water resources, and recreation; the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations have coal deposits of worldwide significance; and the Blackfeet, Crow, and Fort Peck reservations already have realized considerable revenue from oil

TABLE 1.1 Montana Reservations Compared

wells (an average of $400 per member in 1980).1 At the other extreme, the Fort Belknap and Rocky Boy's reservations are natural resource poor and have the highest unemployment rates.

The differences in these figures are not politically neutral. While conflict is present in any community, the task of governing amidst divisiveness will vary from reservation to reservation depending upon economic opportunities and expectations. What principally differentiates these struggles over public matters is the range and complexity of the issues, the variety and skill of the participants, and the effectiveness of governmental machinery. So numerous are the various combinations that an Area Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs said that "in Montana every possible BIA and tribal situation exists."2 Such classifications of Montana reservations can cut several ways: those with a potentially strong economic base and those almost totally dependent on federal assistance; those who are innovative and aggressive and those who merely adopt the forms of bureaucracy; those with a good chance for self-government and those who must rely upon their federal managers.

The aim of this study is not only to scrutinize the workings of Montana's seven reservation governments but also to identify what is representative of tribal politics throughout the West. Contemporary discussions of Indian governments suggest some categories for analysis. Such analytical departure points include the reservation setting and economy, the historical evolution of reservation government, the distinctive brand of politics found on a reservation today, and characteristics of contemporary governmental structure. These four perspectives will be maintained throughout this study and will be discussed briefly below.

The setting of Indian reservations has greatly influenced their fate. They generally are rural settlements in sparsely populated and poorly developed parts of the United States. Marginal land divided into small tracts is capable of providing a living for only a few as farmers and stockmen. Given the limited agricultural capacity of the land, most reservations are overpopulated. The Montana reservations are homelands for some of the nation's largest Indian groups.3 In relatively few cases, the presence of marketable energy resources compensates somewhat for a reservation's social and economic isolation. Four of the seven Montana reservations are among the 15 percent of the country's approximately 300 tribes which have the potential to develop in this way.4 Such economic opportunity, though, increases even more the likelihood of white interference and manipulation and of state governmental challenges to tribal authority.

The setting of Montana's seven Indian reservations has a governmental aspect that is as significant as their geography. Probably the clearest statement of this context is that reservations do not exist in a governmental vacuum. Tribal governments have constant contacts with officials of local, state, and national governments, and these external relationships affect tribal operations just as do internal political relationships.

The boundaries of a reservation can include parts of several counties. Such overlapping jurisdiction can create intergovernmental conflicts. The reservation's presence can affect demand in a county for public services and legal process, while a reservation can experience regulatory problems because its jurisdiction extends to several counties and both Indian and non-Indian owned land. Certain legal and political realities can make the situation extremely difficult: Indians are citizens of the state in which they reside and therefore eligible to participate in the health, welfare, and educational programs of the state; the presence of a reservation within a county can withdraw a significant portion of the county's area from the base of its property tax; and Indian tribes may exercise some forms of civil jurisdiction over non-Indians whose activities have a direct effect on the tribe's political integrity, economic security, or health or welfare. At times intergovernmental understandings have been used to resolve jurisdictional problems. Tribal governments and county sheriff departments have, for example, cross-deputized officers to achieve more effective law enforcement.

State officials provide no less a governmental presence on Indian reservations. In Montana, the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks has sought to regulate Indians' off-reservation hunting; the Department of Health has the authority to administer various regulatory schemes on the reservation to achieve effective statewide programs; the Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services contracts with the tribes for the provision of aging services; and the Department of Natural Resources and Conservation seeks to answer the question whether the state has any jurisdiction over reservation water. As a result of these relationships and pressures, it is impossible for tribal officials to concentrate only on local matters.

The tribal-federal point of contact is the most common and most difficult intergovernmental relationship. The federal government's principal representative to the tribe is the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Bureau's continuous and immediate contact with tribal governments affects their law enforcement, economic development, financial administration, land management, and even constitutional reform. In carrying out its essential governmental functions, a tribe cannot avoid the regulatory presence of the Bureau. The tribes also have frequent contact with other federal agencies. Tribal housing authorities receive grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The American Native Programs of the Department of Health and Human Services provide for certain needs of reservation residents throughout their life. The Department of Labor oversees many federal job training programs on the reservation, and the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management monitor or jointly administer with the tribe many kinds of land use ventures. One Montana reservation deals constantly with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission concerning ownership and operation of a hydroelectric dam. No tribal intergovernmental relationship is as critical as the one with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but tribal politics is influenced by a wide range of federal mandates and pressures.

The features of a tribe's pre-Indian Reorganization Act government provide another perspective for viewing contemporary tribal government. Prior to 1934, reservation governments evolved, changing to accommodate new situations and struggling to preserve cultural values. Traditional forms were dropped or modified and new forms were incorporated into reservation structures as conditions dictated. For example, United States Indian agents instituted administrative bodies when they sought tribal help to run the reservation. High-level federal officials added to reservation governance in other ways. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ezra H. Hayt ordered Indian agents in 1878 to create reservation police forces to maintain law and order, and in 1883 Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller added American trial and punishment procedures in his directive authorizing the creation of Courts of Indian Offenses,5 later known as "25 CFR" courts. Tribal governing bodies during these years presided over land sales and land leases and eventually assumed greater responsibility for general reservation welfare. On the northern plains, tribal decision-making bodies varied from a general council operating with an unwritten constitution to a small business committee made legitimate by a written document. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and the ensuing tribal constitutions minimized differences between tribal governments and addressed the continuing issue: how to reconcile traditional practice with contemporary pressures.

Politics in any setting has to do with conflict over issues of public policy and the resolution of that conflict. Reservation politics—a third vantage point on contemporary tribal government—always tend to be lively, but the factionalism that gives rise to the conflict can have various sources. It can stem from several tribes being confederated on one reservation. It can be based upon differences among clans, religions, places of residency, blood quantum, and the patronage practices of tribal administrations. It can be the result of different views of past events, such as treaties or the Indian Reorganization Act. The rate and mode of political participation on reservations can also vary. Differences can be found in election turnout and in the use of other participation me...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 The Contours of Reservation Politics

- 2 Indian Law and Tribal Government

- 3 The Blackfeet: Their Own Government to Help Them

- 4 The Crow: A Politics of Risk

- 5 The Northern Cheyenne: A Politics of Values

- 6 The Fort Peck Reservation: The Factor of Leadership

- 7 The Fort Belknap Reservation: The Reality of Poverty

- 8 The Rocky Boy's Reservation: A Struggle for Government

- 9 The Flathead Reservation: From Enclave to Self-Government

- 10 Reflections on Tribal Government

- Bibliography