eBook - ePub

Single-Word Reading

Behavioral and Biological Perspectives

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the first title in the new series, New Directions in Communication Disorders Research: Integrative Approaches, this volume discusses a unique phenomenon in cognitive science, single-word reading, which is an essential element in successful reading competence. Single-word reading is an interdisciplinary area of research that incorporates phonolog

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Single-Word Reading by Elena L. Grigorenko,Adam J. Naples in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Inclusive Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Continuity and Discontinuity in the Development of Single-Word Reading: Theoretical Speculations

The capacity to identify single written words accurately and fluently is the fundamental process in reading and the focus of problems in dyslexia. This chapter takes the form of a speculative account of the early stages of the development of word recognition and makes reference to research carried out in the literacy laboratory at the University of Dundee. It is an expression of a viewpoint and a set of hypotheses and not an attempt at a comprehensive review of the literature on the development of word recognition.

A clear sequential account is needed in order to pinpoint when and how development begins to go wrong in cases of dyslexia and to provide a rationale for remedial instruction (Frith, 1985). The basis of such an account is a theory of literacy development. A number of differing approaches can be identified, including: (1) theories that focus on the causes of reading progress or difficulty, with the assumption that development is constrained by cognitive or sensory functions or by biological or cultural factors (Frith, 1997); (2) computational models that attempt the simulation of development using connectionist learning networks (Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989); (3) stage models that identify a cumulative series of qualitatively distinct steps in reading development (Marsh et al., 1981; Frith, 1985); and (4) Models which identify overlapping phases of development, including foundational aspects (Ehri, 1992; Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1989; Seymour, 1990, 1997, 1999, in press). The theoretical account proposed in this chapter falls within the purview of the phase models and includes reference to causal factors in the nature of the spoken and written language, educational factors, and an interactive relationship between orthography and linguistic awareness.

Primitive Pre-Alphabetic Visually Based Word Recognition

Some theories propose an early stage in which word recognition is based on visual characteristics. Gough & Hillinger (1980) described this as ‘associative’ learning, and Marsh, Freidman, Welch & Desberg (1981) as ‘rote’ learning. Similarly, Frith (1985) postulated an initial ‘logographic’ stage, and Ehri’s (1992) account of ‘sight word’ learning includes a preliminary ‘pre-phonetic’ phase. The reference here is to a developmentally early form of word recognition which occurs in the absence of alphabetic knowledge. Words are distinguished according to a process of ‘discrimination net’ learning (Marsh et al., 1980) in which the minimal visual features necessary for choice between items within a restricted set are highlighted. Learning usually involves flash cards and rapid identification of words on sight and typically includes public signs and logos as well as high interest vocabularies such as names of family members or classmates. Teachers may reinforce the approach by emphasising iconic aspects of written words, such as the two eyes in ‘look’ or the waggy tail at end of ‘dog’.

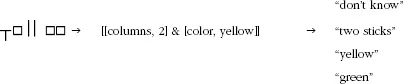

Seymour & Elder (1986) studied a class of Primary 1 children, aged 5 yrs, in Scotland who were learning under a regime which emphasised whole word learning (flash cards and books) in the absence of teaching of the alphabet or decoding procedures. This study illustrates some characteristics of primitive pre-alphabetic word identification: Errors were always refusals or word substitutions taken from the set of learned words. Each word had a physical identifying feature, such as the “two sticks” in ‘yellow’. Confusions occurred due to letter orientation and rotation (b,d,p,q; n, u; w, m). The position of the identifying feature was not critical in the early stages of learning. Thus, Seymour & Elder found that, for a particular child, the shape of the letter K served as a distinctive feature for the identification of the word ‘black’. Tests with nonsense strings in which the ‘k’ was located in different positions all elicited the response “black”. Thus, reading is essentially word specific and reliant on identifying features rather than global word shape or outline. Unfamiliar forms (either words which have not yet been taught or nonwords) cannot be read and their presentation results in refusals (“don’t know” responses) or word substitution errors.

In this mode of reading, visual words will initially be treated as members of a special object class for which the semantic coding is descriptive of the identifying feature plus an associative mnemonic link to a concept. e.g.,

where [] designates a semantic representation, & is an associative link, and “” is a speech code. Since, in this scheme, word selection is semantically mediated, the occurrence of semantic substitution errors is a theoretical possibility. These errors occur in the reading of deep dyslexic patients and it is of interest that a few examples were observed among the children studied by Seymour & Elder (1986). Thus, the feature [colour] could result in the production of the wrong colour name, e.g., “green”. However, this process will be restricted according to the content of the word set involved. Seymour & Elder demonstrated that children possessed a rather precise knowledge of the words which were included in their “reading set” and the words which were not. This suggests the existence of a “response set” which is isolated within a store of phonological word-forms and is the sole source of possible responses. It follows that semantic errors will normally occur only to the extent that a number of words in the store share closely overlapping semantic features. Colour names may be one such case, since they are quite likely to occur in beginning reading schemes.

Some commentators have argued that this primitive form of word identification is not a necessary first step in learning but rather an optional development which is not observed in some languages (e.g., German or Greek) and which is seen in English only among children who lack alphabetic knowledge (Stuart & Coltheart, 1988). One possibility is that the primitive process is unrelated to subsequent reading and is effectively discarded when the formal teaching of the alphabetic principle begins (Morton, 1989). For example, Duncan & Seymour (2000) found that expertise in logo recognition in nursery school conferred no subsequent advantage in reading. The other possibility is that the primitive process, although not a basis for subsequent word recognition, is nonetheless preserved as an element in memory. An argument here is that some forms of script, such as poorly formed handwriting, may require recognition via visual features or a distinctive configuration. In addition, primitive pre-alphabetic reading shares aspects with neurological syndromes such as ‘deep dyslexia’ (Coltheart, Patterson & Marshall, 1980). Patients with this condition lack alphabetic knowledge, are wholly unable to read unfamiliar forms such as simple nonwords, and yet show a residual capacity for recognition of common words with concrete meaning such as predominate in early school books (‘clock’, ‘house’, etc). This preserved reading could be a surviving trace of the primitive recognition function, possibly a form of ‘right hemisphere’ reading which becomes visible when the normal left hemisphere reading system has been abolished. Imaging studies which suggest that right hemisphere activity which is detectable in the early stages of learning tends to reduce or disappear as development proceeds are consistent with this idea (Turkeltaub, Gareau, Flower, Zefiro & Eden, 2003).

In summary, it seems likely that a primitive mode of word recognition (sometimes called “logographic” reading) exists in a form which is functionally (and perhaps anatomically) distinct from the standard alphabetically based reading process. This function may be directly observable only in children who learn to read without alphabetic tuition or in cases where neurological factors intervene to destroy or prevent the creation of an alphabetic system.

Symbolic Versus Pictorial Processing

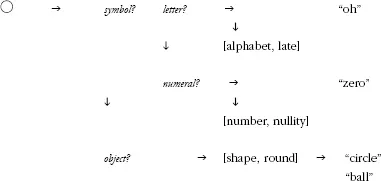

In the primitive form of reading described above a written word is treated as a visual object. The words are members of a set of objects, an object class, in which the members share various features (horizontal extension, density) much like many other object classes (faces, dogs, chairs, trees) where there may be a high level of similarity combined with variations of detail which are critical for distinguishing members of the class one from another. In earlier discussions (Seymour, 1973, 1979), I argued that there was a pictorial channel and memory system which was responsible for recognition of objects, colours, shapes and scenes and for mapping onto a semantic level from which a name or speech output could be selected. This is distinguished from a symbolic channel and memory system which develops for the restricted purpose of dealing with a sub-class of conventionally defined visual objects, most notably the written forms of the numerals and the letters of the alphabet. Various arguments can be put forward to support this distinction. In my own work, I referred to experimental studies by Paul Fraisse which were concerned with the “naming vs reading” difference. This refers to a reaction time difference (vocal RT to name a symbol is faster than RT to name a colour patch or shape or object picture) and to a differential effect of ensemble size (the effect of variation in the number of stimuli involved in a mapping task is larger for objects than for symbols). For example, Fraisse (1966) demonstrated that the shape O is named more rapidly as “oh” or “zero” within a symbol set than as “circle” within a shape set.

According to this argument, the symbol processing channel develops in a way which is functionally and neurologically distinct from the picture and object processing channel. A key aspect of this distinction is that picture processing involves semantic mapping as an initial step, so that naming an object or colour involves the sequence: object → semantic representation → name selection, whereas symbol processing may involve direct mapping to a name: symbol → name selection. A preliterate child has no symbol processing system and will treat all visual shapes and patterns as pictures to be processed in terms of their semantics. The letters of the alphabet and the arabic numerals may initially be supported by the object processing system but will normally be quite quickly segregated and referred to a new system. This specialised channel operates on members of clearly defined and bounded classes (the numerals, 0-9, and the upper and lower case letters of the alphabet), and incorporates feature definitions which allow allocation to a subset as well as discrimination within each subset and tolerance of variations which may occur due to the use of differing fonts or handwritten forms. One feature which has to be taken into account in the symbolic channel is that orientation is a significant issue for identification of symbols (‘n’ is different from ‘u’ and ‘b’ is different from ‘d’).

In this discussion, a key assumption is that the implementation of a segregated symbol processing channel is the critical first step in the formation of a visual word recognition system and competence in reading and spelling. Following the establishment of the symbol processing channel, there is an augmentation in the architecture of the cognitive system, so that incoming visual stimuli may be classed as pictorial or as symbolic and processed accordingly.

Logically, this seems to require some kind of early contextual test to decide if the input is a valid candidate for processing via the symbolic channel, and, if so, whether it is classifiable as a letter or as a numeral. Allocation to the symbol channel allows direct access to a store of symbol names. The symbols may, additionally, have a semantic representation expressing set membership, location in the conventional sequence, and aspects such as magnitude. This information might be accessed through the name or directly by an alternative pathway. If the input is not classed as a symbol it will be treated as an object and processed via the system of object semantics.

Alphabetic Process

In line with this proposal, most theoretical accounts of reading development propose that the (optional) primitive visual phase of development is followed by a phase of alphabeticisation. Typically, this refers to the mastery of the ‘alphabetic principle’ of phonography according to which written words may be segregated into a left-to-right series of letters, each of which can be decoded as standing for a segment of speech. These segments correspond to the linguistic abstractions, the phonemes, by which the set of vowels and consonants composing the syllables of the spoken language are identified. This shift is well described in Frith’s (1985) account. She proposed an initial phase, described as logographic, which corresponds to the primitive form of pre-alphabetic reading described above. This is followed by an alphabetic phase during which a new strategy involving systematic sequential conversion of letters to sounds is adopted. Frith took the view that the alphabetic process might have its origin in writing and spelling. Learning to write is naturally sequential, requiring the capacity to segment speech into a series of sounds, select a letter for each sound, and produce the graphic forms seriatim in the correct order. This strategy of proceeding in a sequential letter-by-letter manner may be transferred to reading as the model for a decoding procedure based on letters and sounds. Marsh et al.. (1981) used the term sequential decoding to refer to this strategy.

Letter–Sound / Decoding Distinction

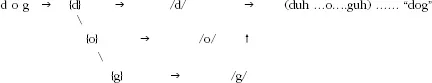

For the purposes of the present discussion, it seems desirable to emphasise certain distinctions which may not have featured in the accounts provided by Marsh et al. and Frith. A first point is that a clear distinction needs to be made between (1) basic letter-sound knowledge, and (2) the mechanism or procedure of sequential decoding. Letter-sound knowledge is the foundation of the symbol processing channel described above. The reference is to a bi-directional channel in which the input of a visual symbol leads directly to the production of its spoken name and the auditory input of the spoken name leads directly to the production of the written form or to visual recognition (as in auditory-visual same-different matching). Sequential decoding is an operation which is applied to letter-sound knowledge. It requires the addition of an analytic procedure, sometimes referred to as “sounding out”, which proceeds in a strict spatially oriented (left-to-right) sequence and involves the conversion of each symbol to a sound and the amalgamation of these sounds into a unified (“blended”) pronunciation:

where {} is a grapheme, // is a phoneme, (..) is overt or covert letter sounding, and “” is an assembled (blended) speech ou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- List of Contributors

- 1. Continuity and discontinuity in the development of single-word reading: Theoretical speculations

- 2. The visual skill “reading”

- 3. The development of visual expertise for words: The contribution of electrophysiology

- 4. Phonological representations for reading acquisition across languages

- 5. The role of morphology in visual word recognition: Graded semantic influences due to competing senses and semantic richness of the stem

- 6. Learning words in Zekkish: Implications for understanding lexical representation

- 7. Cross-code consistency in a functional architecture for word recognition

- 8. Feedback-consistency effects in single-word reading

- 9. Three perspectives on spelling development

- 10. Comprehension of single words: The role of semantics in word identification and reading disability

- 11. Single-word reading: Perspectives from magnetic source imaging

- 12. Genetic and environmental influences on word-reading skills

- 13. Molecular genetics of reading

- 14. Four “nons” of the brain–genes connection

- 15. Dyslexia: Identification and classification

- 16. Fluency training as an alternative intervention for reading-disabled and poor readers

- 17. Neurobiological studies of skilled and impaired word reading

- 18. Nondeterminism, pleiotropy, and single-word reading: Theoretical and practical concerns

- Author Index

- Subject Index