eBook - ePub

Brachial Plexus Injuries

Published in Association with the Federation Societies for Surgery of the Hand

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Brachial Plexus Injuries

Published in Association with the Federation Societies for Surgery of the Hand

About this book

This is a comprehensive guide to the management of brachial plexus injuries. International experts have been assembled to comment on their areas of research and clinical experience, and the resulting volume is definitive.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brachial Plexus Injuries by Alain Gilbert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Obstetrical Paralysis

16 Aetiology

JM Hans Ubachs and Albert (Bart) CJ Slooff

History

The aetiology of the obstetric brachial plexus injuries has an interesting history. As early as 1764, Smellie suggested the obstetric origin of a paralysis of the arm in children. But only in 1872, in the third edition of his book De l’électrisation localisée et de son application à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique , Duchenne de Boulogne described four children with an upper brachial plexus lesion as a result of an effort to deliver the shoulder. The classical description by Erb in 1874 concerned the upper brachial plexus paralysis in adults, with the same characteristics as those described by Duchenne de Boulogne. Using electric stimulation, he found in healthy persons a distinct point on the skin in the suprascapular region, just anterior to the trapezius muscle, where the same muscle groups could be contracted as those affected in his patients. It is the spot where the fifth and sixth cervical roots unite, and where they are optimally accessible to electric current by virtue of their superficial position. Pressure on this ‘point of Erb’, caused either by fingers by traction on the armpits, by forceps applied too deep, or by a haematoma were for Erb, and many obstetricians after him, the only possible cause of the lesion.

But not everybody accepted the compression theory. Poliomyelitis and toxic causes were mentioned. Some even pointed to the possibility of an epiphysiolysis of the humerus, caused by congenital lues, and consequently a paralysis of the arm. Doubts about the pressure theory, however, were raised as a result of observation of Horner’s syndrome, indicating damage of the sympathical nerve, together with an injury of the lower plexus. Augusta Klumpke, the first female intern in Paris, explained in 1885 Horner’s sign in the brachial plexus lesion by avulsions of the roots C8–T1 and involvement of the homolateral cervical sympathic nervous system (Klumpke 1885). Klumpke later married Dejerine, and therefore the lower plexus palsy is sometimes called the Dejerine–Klumpke paralysis, as opposed to the upper plexus palsy, which is named the Erb–Duchenne paralysis. Thornburn (1903) was one of the first to assume that the injury was the result of rupture or excessive stretching of the brachial plexus during the delivery.

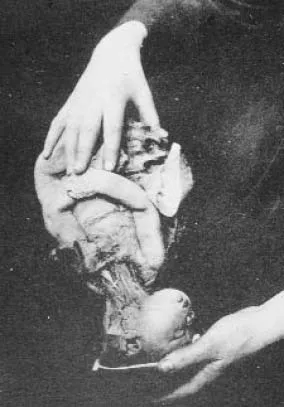

Figure 1

Engelhard’s photograph demonstrating the result of excessive stretching during the delivery (Engelhard 1906).

Engelhard’s photograph demonstrating the result of excessive stretching during the delivery (Engelhard 1906).

Pathogenesis

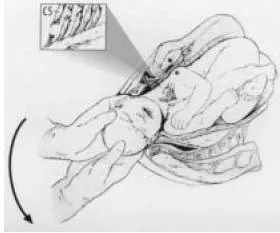

To test Thornburn’s assumption, Engelhard investigated the influence of different positions and assisted deliveries on a dead fetus, in which the brachial plexus was dissected. In his doctoral thesis he demonstrated in 1906, with for that period excellent photographs, that the pressure theory was highly improbable (Fig. 1). Obstetric injury of the brachial plexus could only be the result of excessive stretching of that plexus during the delivery. In particular, he warned against strong downward traction of the fetal head developing the anterior shoulder in cephalic deliveries, and extensive lateral movement of the body in breech extractions. And his words still have their validity. More recently, Metaizeau et al (1979) repeated these studies and explained the differences in injury. The results of these investigations have been confirmed by our clinical and surgical observations (Ubachs et al 1995, Slooff 1997). Shoulder dystocia occurs mostly unexpected, and it is one of the more serious obstetric emergencies. The shoulder is impacted behind the symphysis pubis, and although there is a long list of manoeuvres to disimpact the shoulder, not one is perfect. Excessive dorsal traction, the first reaction in that situation, bears the danger of overstretching with consequent damage of the brachial plexus (Fig. 2). In breech presentation, even of small infants, the injury is caused by difficulties in delivering the extended and entrapped arm and therefore a combination of forceful traction with too much lateral movement of the body.

Reconstructive neurosurgery of the obstetric brachial plexus lesion, together with neurophysiological and radiological investigation, gives the opportunity to gain a clear understanding of the relationship between the anatomical findings during operation and the obstetric trauma. The injury may be localized in the upper or lower part of the brachial plexus, resulting in different phenotypes. Erb’s palsy results from an injury of the spinal nerves C5–C6 and sometimes C7. It consists of a paralysis of the shoulder muscles, resulting in a hanging upper arm in endorotation, a paralysis of the elbow flexors and consequently an extended elbow in pronating position, caused by the paralysis of the supinators. Combination with a lesion of C7 results in a paralysis of the wrist and finger extensors and the hand assumes the so-called waiter’s tip position. The total palsy, often incorrectly called Klumpke’s palsy, is caused by a severe lesion of the lower spinal nerves (C7–T1) but is always associated with an upper spinal nerve lesion of varying severity. The impairment mainly includes a paralysis of the muscles in forearm and hand, sometimes causing a characteristic clawhand deformity, and sensory loss of the hand and the adjacent forearm. Involvement of T1 is frequently paralleled by cervical sympathetic nerve damage, an injury that will give rise to Horner’s syndrome.

Figure 2

Excessive dorsal traction in shoulder dystocia with consequent damage of the brachial plexus. (From Ubachs et al 1995.)

Excessive dorsal traction in shoulder dystocia with consequent damage of the brachial plexus. (From Ubachs et al 1995.)

Furthermore, stretching of the brachial plexus may result in two anatomically different lesions with different morbidities. The lesions are easily distinguished during surgery. Either the nerve is partially or totally ruptured beyond the vertebral foramen, causing a neuroma from expanding axons and Schwann’s cells at the damaged site, or the rootlets of the spinal nerve are torn from the spinal cord, a phenomenon called an avulsion.

Table 1 Demographic and obstetric characteristics of the two obstetric brachial plexus lesion (OBPL) populations in relation to their respective reference populations. Values are given as percentages (From Ubachs et al 1995)

Patients

Study of the first 130 patients, operated on from April 1986 to January 1994 in De Wever Hospital (today the Atrium Medical Centre) in Heerlen, The Netherlands, offered the opportunity to prove Engelhard’s assersion in 1906. Moreover, it was interesting to determine whether the presentation of the fetus during the preceding delivery – breech or cephalic – contributed to the localization and anatomical severity of the lesion. The results of that study, the first where the anatomical site of the damage was compared with the preceding obstetric events, were published in 1995. The indication for neurosurgical intervention was based on the criteria from Gilbert et al (1987). The obstetric history was traced by analysis of the obstetric records made at the delivery and compared much later with the anatomical findings at surgery. Demographic and obstetric data regarding a large proportion (146 533) of the 196 700 deliveries in The Netherlands in 1992 were obtained from The Foundation of Perinatal Epidemiology in The Netherlands (PEN) and the Dutch Health Care Information Centre (SIG). These data were used to identify specific features in the study population (Table 1).

Of the operated infants with obstetrics brachial plexus lesions (OBPLs), 102 were born in cephalic and 28 in breech position. Patients who had been delivered in cephalic presentation were born more frequently from a multiparous mother, were more frequently macrosomic, experienced intrapartum asphyxia more often and required instrumental delivery more often. Patients born in breech differed from the reference population by a higher incidence of intrapartum asphyxia. The gestational age at birth did not differ significantly.

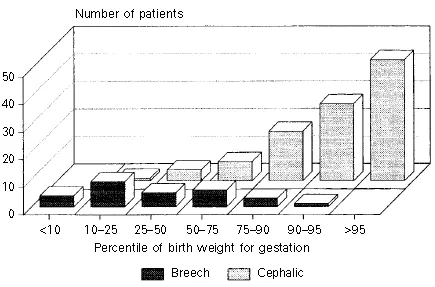

In one-third (40/130) of the OBPL population, the preceding pregnancy had been complicated by treated gestational diabetes, the suspicion of idiopathic macrosomia (percentile of birth weight for gestation ≥ 90), obesity and even the explicit wish to give birth in a standing position, a strategy which tends to aggravate mechanical problems encountered during the second stage. Two-thirds (87/130) of the infants with OBPLs were delivered by multiparous mothers and, in almost half of them (39/87) macrosomia, instrumental delivery and/or other potentially traumatic manipulations had complicated the second stage of labour. Whereas the cephalic group was characterized by a disproportionate number of macrosomic infants, the distribution of the percentile of birth weight for gestation in the breech group did not differ significantly (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The mean neonatal weight of the children born in the cephalic position was 4334 g with a range from 2550 to 6000 g. Infants born by breech weighed a mean 3050 g with a range from 1230 to 4000 g. In spite of this marked weight difference, the incidence of mechanical problems during passage of the birth canal and that of intrapartum asphyxia (1 min Apgar score ≤ 6) was similar in the two groups (Table 2). It is uncertain whether the asphyxia was caused by the difficulty in delivery, or if it was one of the factors in the nerve damage by causing muscular hypotonia. Obviously, excess macrosomia in the cephalic group explains the high incidence of shoulder dystocia. It is interesting that twice as many rightthan left-sided injuries were observed in the children delivered in vertex presentation. This is most likely to be a direct consequence of fetal preference for a position with the back to the left side, and hence a vertex descent in a left occipital anterior presentation (Hoogland and de Haan 1980). The preference for the right side was also noted for the breech group. However, this was not significant, possibly because of the smaller group size (Table 3).

Table 2 Traumatic birth and intrapartum asphyxia in the two birth groups. Values are given as n (%). Differences (P ) not significant

Table 3 Incidence of the left- and right-side lesions: cephalic birth (n = 102) and breech (n = 28). Values are given as n (%)

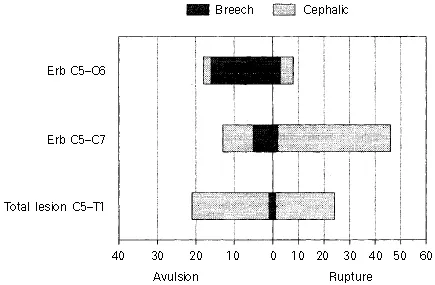

An unexpected finding was the difference in clinical and anatomical type of lesion between the children born in breech and cephalic presentations (Table 4 and Fig. 4). Mechanically, a difficult breech delivery with often brusque manipulation to deliver the first arm, together with excessive traction on the entire neck was expected to predispose towards more extensive damage reflected in the Erb’s type C5–C7 or the total C5–T1 lesions. Similarly, overstretching by traction and abduction in an attempt to deliver the first shoulder was expected to predispose for C5–C6 damage. To our surprise, two-thirds (19/28) of the injuries after breech delivery consisted of pure Erb palsies (C5–C6) caused, in the majority of cases (16/19), by a partial or complete avulsion of one or both spinal nerves. Total lesions were rare in the breech group. Conversely, the most common lesion after cephalic birth was the more extensive Erb’s palsy (C5–C7) usually resulting from an extraforaminal partial or complete nerve rupture, closely followed by the total palsy. In fact, a total palsy was an almost exclusive complication (43/45) of cephalic delivery, with nerve rupture and nerve avulsion seen equally frequently. Interestingly, if in this group the lesion was not total (C5–T1), the damage was always more severe as indicated by the incidence of nerve rupture. Apparently, unilateral overstretching of the angle of neck and shoulder in the cephalic group led to a more extensive damage, including the lower spinal nerves of the plexus.

Figure 3

The weight at birth of 130 children with OBPLs.

The weight at birth of 130 children with OBPLs.

Table 4 Effect of presentation at birth on type and severity of the OBPL birth groups. Values are given as percentages (From Ubachs et al 1995)

An explanation of this phenomenon might be sought in tight attachment of the spinal nerves C5 and C6 to the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae (Sunderland, 1991). As a result of that, unilateral overstretching in shoulder dystocia preferentially leads to an extraforaminal lesion of the upper spinal nerves and often to an avulsion of the lower spinal nerves C8–T1 from the spinal cord. A different causal mechanism, however, should be considered in difficult breech deliveries (Slooff and Blaauw, 1996). Hyperextension of the cervical spine and consequently a forced hyperextensive moment or elongation of the spinal cord in such a delivery, combined with the relatively strong attachment of the spinal nerves C5 and C6 to their transverse processes, might cause an avulsion by acting directly on the nerve roots between their attachment to the cord and their fixed entry in the intervertebral foramen. Sunderland calls this the ‘central mechanism’ of an avulsion (Sunderland 1991, Fig. 18.7, p. 157).

Associated lesions were frequent. Fractures of the clavicle or the humerus were evenly distributed over the two groups, whereas persistent paralysis of the phrenic nerve was noted more frequently in infants born by breech and bilateral OBPL was seen exclusively after a breech delivery (Table 5).

Figure 4

Presentation at birth, morbidity and type of lesion in 130 children. (From Ubachs et al 1995)

Presentation at birth, morbidity and type of lesion in 130 children. (From Ubachs et al 1995)

Table 5 Incidence of associated lesions in the two birth groups. None of the children had a spinal cord or facial nerve lesion. Values are given as n (%) (From Ubachs et al 1995)

Intrauterine maladaptation was never suspected, as no infant in these series was born by Caesarean section and all vaginal deliveries were either operative or were complicated by other potentially traumatic manipulations. A Caesarean section, for that matter, is not always safe and atraumatic: especially in malpositions, a Caesarean delivery can be extremely difficult. As early as 1980, Koenigsberger found in neonates with plexus injuries whose deliveries were uncomplicated, in the first days of life electromyographic changes characteristic of muscle denervation, which, in adults, take at least 10 days to develop. In ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Contributors

- The Brachial Plexus

- The Adult Traumatic Brachial Plexus

- Obstetrical Paralysis

- Special Lesions