The Archaeology of Seeing

Science and Interpretation, the Past and Contemporary Visual Art

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Archaeology of Seeing

Science and Interpretation, the Past and Contemporary Visual Art

About this book

The Archaeology of Seeing provides readers with a new and provocative understanding of material culture through exploring visual narratives captured in cave and rock art, sculpture, paintings, and more.

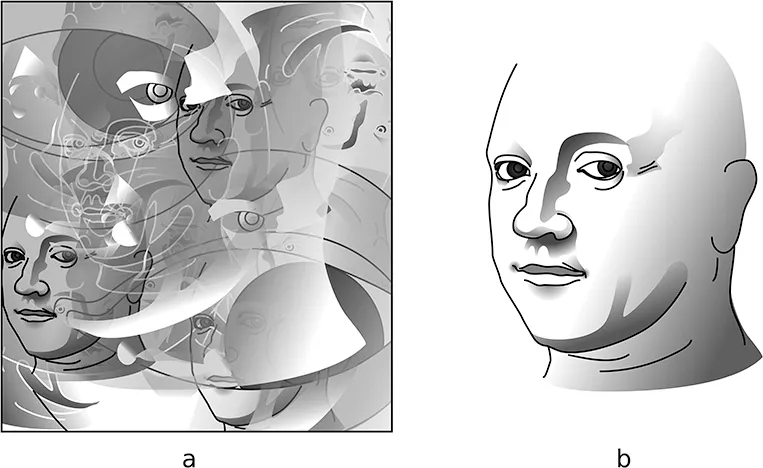

The engaging argument draws on current thinking in archaeology, on how we can interpret the behaviour of people in the past through their use of material culture, and how this affects our understanding of how we create and see art in the present. Exploring themes of gender, identity, and story-telling in visual material culture, this book forces a radical reassessment of how the ability to see makes us and our ancestors human; as such, it will interest lovers of both art and archaeology.

Illustrated with examples from around the world, from the earliest art from hundreds of thousands of years ago, to the contemporary art scene, including street art and advertising, Janik cogently argues that the human capacity for art, which we share with our most ancient ancestors and cousins, is rooted in our common neurophysiology. The ways in which our brains allow us to see is a common heritage that shapes the creative process; what changes, according to time and place, are the cultural contexts in which art is produced and consumed. The book argues for an innovative understanding of art through the interplay between the way the human brain works and the culturally specific creation and interpretation of meaning, making an important contribution to the debate on art/archaeology.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

How contemporary is prehistoric art?

Introduction

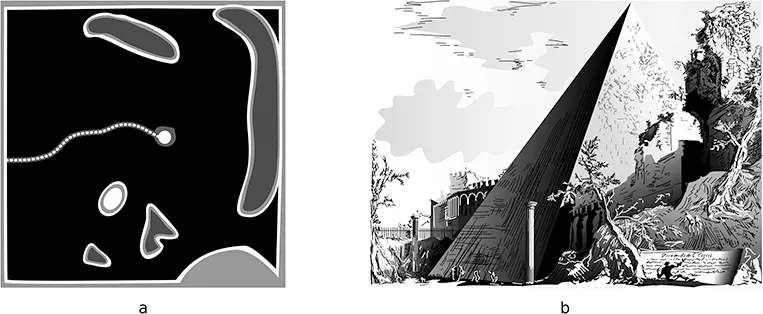

Defining visual vocabulary

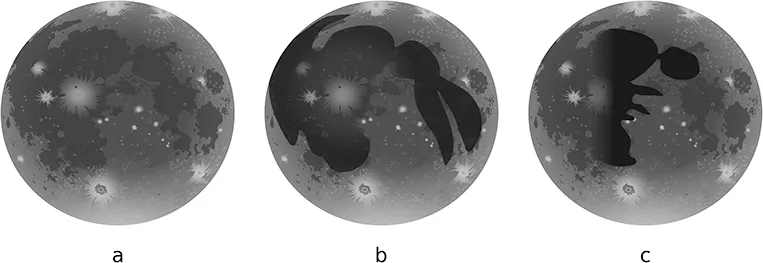

Visual art and the brain

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. How contemporary is prehistoric art?

- 2. The origins of art

- 3. The gallery: unveiling visual narrative

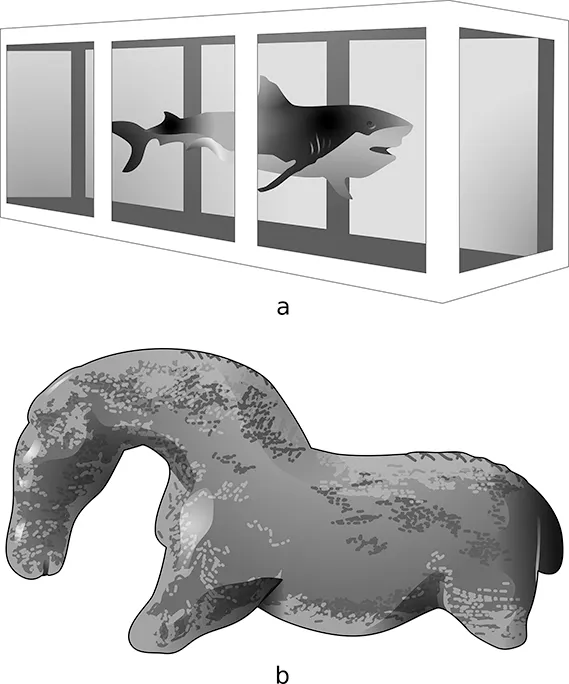

- 4. Power of display: the artist and the object

- 5. Embodiment and disembodiment: the corporeality of visual art and interwoven landscapes

- 6. Portraiture and the reverence of the other

- 7. Conclusion

- Index