- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The time we have to care for one another, especially for our children and our elderly, is more precious to us than anything else in the world. Yet we have more experience accounting for money than we do for time. In this volume, leading experts in analysis of time use from across the globe explore the interface between time use and family pol

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Family Time by Michael Bittman,Nancy Folbre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The big picture

1 A theory of the misallocation of time

Nancy Folbre

In 1965, Gary Becker published an article entitled “A Theory of the Allocation of Time” that called attention to the productivity of nonmarket work. Laying an important cornerstone of the “new home economics,” Becker extended neoclassical economic theory beyond the traditional realm of consumer choice. He also reinforced its most reassuring claim: Individuals pursuing their own self-interest by maximizing their utility make choices that are efficient not only for them, but also for society as a whole. Related contributions by Jacob Mincer (1962) and Reuben Gronau (1973, 1977, 1980) clarify the implications for gender roles: Women choose to specialize in nonmarket production within the home because this represents their best option. Efforts to restrict or modify such choices would likely impose efficiency losses on society as a whole.

This confidence in individual choice finds empirical expression in human capital models that explain wages as the outcome of individual decisions to invest in education and experience. Application to the sexual wage differential is straightforward. Women choose to specialize in nonmarket production because they have a comparative advantage in breastfeeding and infant care. As a result, they accumulate fewer market-specific skills and earn lower wages than men. While this causality is questioned by those who argue that labor market discrimination also plays a role, the underlying theory of time allocation excites little disagreement among economists.1 New sources of high-quality data on time-use in Canada, Australia, Europe, and the United States remain underutilized by economists, who seldom integrate time-use into models of household decision making (Apps 2002). Many sociologists studying time-use discount Becker’s arguments without directly confronting them.

In this essay, I argue that Becker’s theory of time allocation and female specialization in nonmarket family work overstates the role of individual decisions and exaggerates the efficiency of social outcomes. Distributional conflict influences decisions made by families and also shapes the social institutions that govern the allocation of time. Time allocation does not conform to the idealized processes of competitive markets because it involves important coordination problems that cannot be solved entirely by the independent decisions of individuals. Time devoted to the care of children and other dependent family members has effects that reach beyond the household. Individuals often face strategic dilemmas in which the difficulties of establishing and enforcing agreements make it unlikely they will get what they want. The social institutions that evolve to help solve these coordination problems are shaped by collective action, and often prove resistant to change even when they lead to inefficient outcomes.

The first section of this chapter reviews the strengths and weaknesses of the neoclassical theory of time allocation, emphasizing the need for situating its insights within a more interdisciplinary approach. The second section focuses on reasons why decentralized individual choices may not lead to efficient outcomes. Time devoted to the production and maintenance of human capabilities creates positive externalities or spillover benefits. Unrestricted competition can increase the opportunity cost of time devoted to family care by contributing to “arms race” and free rider problems. The third section describes some of the social institutions that have emerged as ways of addressing these coordination problems. Cultural norms and legal rules often restrict the length of the work day; discriminatory rules against female participation in wage employment as well as public supports for childrearing have served to limit competitive pressures on the allocation of time to dependents.

That such rules have had some positive effects does not suggest that they have been either efficient or fair. Indeed, a number of explicit and implicit restrictions on maternal employment have historically contributed to the subordination of women. New efforts are underway in many countries to develop more equitable and efficient ways of coordinating paid work and family responsibilities. These efforts have much to gain from an economic analysis of factors that can contribute to the misallocation of time.

The neoclassical theory of time allocation

The strength of the neoclassical approach to human behavior lies in its elegant formulation of the logic of individual choice. In order to explore this logic, most practitioners set aside questions concerning the origins of individual preferences, the initial distribution of assets, and institutional rules. This makes it possible to focus on responses to changes in prices and incomes. It also makes it difficult to question whether a voluntary exchange is “fair” or “unfair.” No voluntary exchange takes place unless both parties expect to benefit from it. Hence, voluntary exchanges should lead to a situation in which no person can be made better off without making another worse off (or, in technical terms, Pareto optimality).

Limitations of scope

Some critics reject this emphasis on rational choice out of hand; others, like myself, believe that it offers important insights.2 The notion that individuals consider the economic consequences of their actions is endorsed by many diverse schools of social thought, and the allocation of time clearly has economic consequences. Indeed, it is difficult to explain the relationship between the historical transition from family-based to wage-based employment and fertility decline without resorting to reasoning similar to that which Becker outlines.

To illustrate the more specific mechanics of his approach, consider an individual who has a choice between specializing in producing goods and services for their own consumption (whether on a family farm or in the home) or working for a wage. The wage is determined by the forces of supply and demand in the labor market, and remains the same no matter how many hours of work are supplied to the market. However, the marginal product of labor devoted to nonmarket work is likely to decline after a certain point, simply because of diminishing returns to labor given a fixed supply of capital and other inputs.

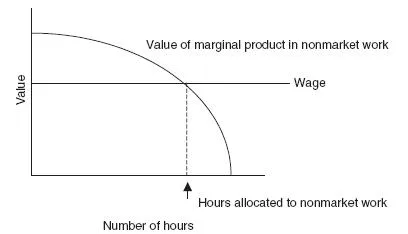

The Rational Economic Man of neoclassical economic theory faces the situation described in Figure 1.1. If we ignore all constraints outside the graph itself, we can predict that he will allocate time to nonmarket work until the value of his product per hour equals the wage. At that point, he is better off reallocating his time to wage employment.3 Any other choice would entail receiving less income or product for the same amount of work.

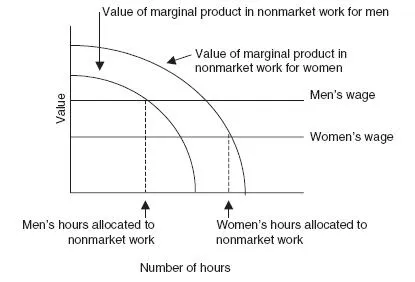

It follows that if men face a higher market wage than women, as illustrated in Figure 1.2, they allocate more time to wage employment, and if their marginal product in nonmarket production is lower than that of women, they will specialize even further. In terms of the possibilities pictured on the graph, men’s decisions are efficient. Whether they are efficient (or fair) from a larger point of view depends largely on the factors determining the shapes and the shifts of these curves. What if, for instance, men earn higher wages because of discrimination against women, or are less competent in nonmarket production because they are never instructed in what are considered “feminine” skills? An answer to the larger efficiency question requires exploration of counterfactual possibilities that are not in the picture.

By focusing attention on the optimal choice for an individual, given relative prices and payoffs, the neoclassical approach carves out a small piece of a larger

Figure 1.1 The allocation of time between nonmarket work and wage employment: simplest case.

Figure 1.2 Allocation of time with gender differences in productivity and wages.

picture. It tells us something important about what is happening on a microeconomic level. For instance, we can infer that if someone chooses to do nonmarket work at home they must value that work more than the next best alternative use of their time. What we cannot infer — without buying into some very restrictive assumptions — is why they value it.

Most neoclassical economists not only take what people want as a given, but argue that preferences do not systematically vary, either across populations or over time (Becker and Stigler 1971). Preferences are, after all, largely unobservable, and it is easy to construct post hoc explanations based on wishful thinking. Gary Becker calls attention to preference formation within families, offering a cogent explanation of why parents might want to inculcate love and altruism in their children (Becker 1996). Yet, he never explores the related question of why societies might want to inculcate solidarity and altruism in their citizens.

Nor is there much interest in which preferences might be considered “good” and which “bad.” Indeed, economists consider a type of preference that many people would consider repugnant — perfect selfishness — not only natural, but also desirable in all market transactions. On the other hand, altruism is considered natural and appropriate to family transactions, without much consideration of just how altruistic individuals in the family should be.

Prediction problems

Conceding the limited scope of the neoclassical approach reduces but does not eliminate its uncomfortable features. By his own account, Becker (1965) hoped to establish a framework for empirical research. Yet remarkably few studies actually set out to test hypotheses regarding time allocation generated by the neoclassical utility maximization framework.4 Scholars have articulated a long list of misgivings, many of which relate to the difficulty of making clear predictions that can be empirically tested.

One misgiving first concerns the nature of preferences for household and family work. In nonmarket activities, it seems particularly obvious that individuals derive benefits from the activities themselves as well as from their outputs. A mother may enjoy the process of playing with her child while she provides necessary care for it. The personal pleasure she enjoys will lead her to allocate more time to this activity than she otherwise would. Her preferences are not directly observable. Therefore, it is impossible to determine to what extent her time allocation is shaped by technology (the value of the service she is providing) and to what extent it is shaped by her preferences (the direct utility derived from the activity itself ) (Pollak and Wachter 1975; Pollak 1999).5

A second problem with empirical predictions concerns the aggregation of individual preferences. Traditional neoclassical theory focuses on individual decision making, but many individuals live in families where decisions to allocate time are shaped by their concern for the welfare of other family members (altruism) as well as strategic expectations of punishment or reward (bargaining). Becker minimizes this problem by treating the family as if it were a single unit, and much of the economic literature on household decision making follows suit.6 But a substantial body of theoretical and empirical research suggests that individual bargaining power affects family decisions (Folbre 1986; Lundberg and Pollak 1996). Patterns of control over individual income lead to differences in the allocation of consumption; it seems likely that they also affect the allocation of time (Apps and Rees 1997; Apps 2002).

Finally, as many critics of human capital models have pointed out, it is difficult to distinguish cause and effect in family time allocation. Do women tend to devote more time to housework and childcare than men do because their wages are lower, or are their wages lower because they devote more time to housework and childcare? The interpretation can run either way (Hersch and Stratton 1997). Even controlling for hours of market work, it may be that the types of responsibilities that women shoulder within the home reduce the energy an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Family Time

- Routledge IAFFE Advances in Feminist Economics

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I The big picture

- PART II Using the yardstick of time to capture care

- PART III Valuing childcare and elder care

- PART IV Parenting, employment, and the pressures of care

- PART V International comparisons

- Note: details of Australian time-use surveys

- Index