eBook - ePub

Phytochemicals

Mechanisms of Action

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Phytochemicals

Mechanisms of Action

About this book

Phytochemicals: Mechanisms of Action is the latest volume in a highly regarded series that addresses the roles of phytochemicals in disease prevention and health promotion. The text, an ideal tool for scientists and researchers in the fields of functional foods and nutraceuticals, links diets rich in plant-derived compounds, such as fruit, vegetabl

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Phytochemicals by Mark S. Meskin, Wayne R. Bidlack, Audra J. Davies, Douglas S. Lewis, R. Keith Randolph, Mark S. Meskin,Wayne R. Bidlack,Audra J. Davies,Douglas S. Lewis,R. Keith Randolph in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Absorption and Metabolism of Anthocyanins: Potential Health Effects

Ronald L. Prior

CONTENTS

Abstract

Introduction

Anthocyanins in Foods

Antioxidant and Other Biological Effects of Anthocyanins In Vitro

Anthocyanins and α-Glucosidase Activity

Anthocyanin Absorption/Metabolism

Gut Metabolism of Anthocyanins

In Vivo Antioxidant and Other Effects of Anthocyanins — Animal Studies

Antioxidant Effects

Vasoprotective Effects

In Vivo Antioxidant and Other Side Effects of Anthocyanins — Human Clinical Studies

Antioxidant Effects

Vascular Permeability

Effects on Vision

Conclusions

References

ABSTRACT

This manuscript reviews literature on anthocyanins in foods and their metabolism and absorption and possible relationships to human health. Of the various classes of flavonoids, the potential dietary intake of anthocyanins is perhaps the greatest(100+ mg/day). The content in fruits varies considerably between 0.25 to 700 mg/100 g fresh weight. Not only does the concentration vary, the individual specific anthocyanins present also are quite different in various fruits. Anthocyanins are absorbed intact without cleavage of the sugar to form the aglycone. The proportion of the dose that appears in the urine is quite small (<0.1%). Plasma levels of anthocyanins are in the range of 1–120 nM following a meal high in anthocyanins, but fasting plasma levels are generally nondetectable. Information is limited as to possible metabolites of anthocyanins in the human. A number of antioxidant-related responses are reviewed in animal models as well as in the human. Anthocyanins can provide protection against various forms of oxidative stress in animal models, however, most of the health-related responses have been observed at relatively high intakes of anthocyanins (2-400 mg/kg BW).

INTRODUCTION

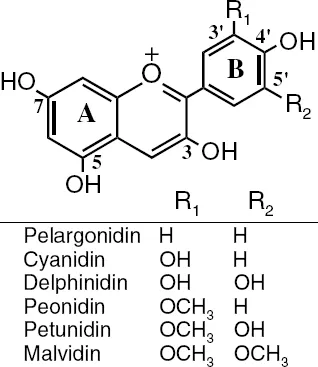

Anthocyanins (Figure 1.1) are water soluble plant secondary metabolites responsible for the blue, purple, and red color of many plant tissues. They occur primarily as glycosides of their respective anthocyanidin-chromophores. The common anthocyanidin aglycones are cyanidin (cy), delphinidin (dp), petunidin (pt), peonidin (pn), pelargonidin (pg), and malvidin (mv). The differences in chemical structure of these six common anthocyanidins occur at the 3’ and 5’ positions (Figure 1.1). The aglycones are rarely found in fresh plant material. There are several hundred known anthocyanins. They vary in 1) the number and position of hydroxyl and methoxyl groups on the basic anthocyanidin skeleton; 2) the identity, number and positions at which sugars are attached; and 3) the extent of sugar acylation and the identity of the acylating agent. Common acylating agents are the cinnamic acids (caffeic, ρ-coumaric, ferulic, and sinapic). Acylated anthocyanins occur in some of the less common foodstuffs such as red cabbage, red lettuce, garlic, red-skinned potato, and purple sweet potato.1

Figure 1.1 Common anthocyanin structures. Sugar moieties are generally on position 3 of the C-ring.

This review will focus on the food content of anthocyanins, their absorption/metabolism, and reports of potential beneficial health effects. Other reviews have been published that deal more with the chemistry of anthocyanins.2,3

ANTHOCYANINS IN FOODS

The distribution of anthocyanins in 26 different common foods is presented in Table 1.1 and Table 1.2. This information is based upon our data as well as information obtained from Macheix et al.,4 editors of a book on fruit phenolics. Cyanidin aglycone occurred in 23 of the 26 foods listed and, overall, seems to be present in about 90% of fruits4 and is the most frequently appearing aglycone compared to all of the others. The glucoside form is present in 23 out of 26 of the foods listed in Table 1.1. The galactoside, arabinoside and rutinoside (6-O-α-L-rhamnosyl-D-glucose) were present in 30 to 40% of the foods in Table 1.1. The rutinoside seems to be present in those foods that do not contain either the galactoside or arabinoside.

Anthocyanin levels (mg/100g fresh weight (FW)) range from 0.25 in pear to 500 in blueberry4 and more than 700 in black raspberry (Table 1.2). Fruits that are richest in anthocyanins (>20 mg/100 g FW) are very strongly colored (deep purple or black). Moyer et al.5 surveyed genotypes of blueberries, blackberries, and black currants for their anthocyanin content. Means ± SEM and the range in mg/100 g fresh weight were 230 ± 89 (34–515), 179 ± 89 (52–607), and 207± 61 (14–411) for blueberries, blackberries, and black currants, respectively. The relative contribution of individual anthocyanins to the total anthocyanins in six fruits that are relatively high in total anthocyanins is presented in Table 1.2. Blueberry is unique in having a large number of individual anthocyanins (15–25). Lowbush blueberry has more of the acylated anthocyanins compared to cultivated blueberries (Highbush and Rabbiteye).6 Black raspberry has one of the highest anthocyanin content of common foods (763 mg/100 g FW) (Table 1.2), with three anthocyanins contributing ~97% of the total anthocyanin content. Other foods that have been reported to contain anthocyanins include onion, red radish, red cabbage, red soybeans, and purple corn.4

In the U.S., the average daily intake of anthocyanins has been estimated to be 215 mg during the summer and 180 mg during the winter.7 However, there are limited quantitative data available, but similar methodology indicates that the concentrations can be quite variable in any one food.1,5 A recent report8 demonstrated that increased childhood fruit intake, but not vegetable, was associated with reduced risk of incident cancer. Thus, childhood fruit consumption may have a long-term protective effect on cancer risk in adults. Because a major difference between fruits and most vegetables is the anthocyanin content, further study is needed to demonstrate a clear relationship between anthocyanin intake and cancer.

Table 1.1 Distribution of anthocyanins in common foods.a

ANTIOXIDANT AND OTHER BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF ANTHOCYANINS IN VITRO

Like other flavonoids, anthocyanins have strong antioxidant capacity as measured by in vitro assays. Cyanidin glycosides tend to have higher antioxidant capacity than peonidin- or malvidin-glycosides,9 likely due to the free hydroxyl groups on the 3’ and 4’ positions in the B-ring of cyanidin. Pool-Zobel et al.10 compared anthocyanin extracellular and intracellular antioxidant potential in vitro and in human colon tumor (HT29 clone 19A) cells. Isolated compounds (aglycones and glycosides) and complex plant samples were powerful antioxidants in vitro as indicated by a reduction in H2O2-induced DNA strand breaks in cells treated with complex plant extracts; however, endogenous intracellular generation of oxidized DNA bases (comet test) was not prevented.10 These data suggest that anthocyanins might not accumulate to sufficient concentrations intracellularly to have significant antioxidant effects. Youdim et al.11 found that the incorporation in vitro of anthocyanins (1 mg/ml) from elderberry within the cytosol of endothelial cells (EC) was considerably less than that in the membrane. Uptake within both regions appeared to be structure dependent, with monoglycoside concentrations higher than those of the diglucosides in both compartments. Enrichment of EC with elderberry anthocyanins conferred significant protective effects against oxidative stressors such as (1) hydrogen peroxide, (2) 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH), and FeSO4/ascorbic acid. These findings may have important implications on preserving EC function and preventing the initiation of EC changes associated with vascular diseases.11

Hibiscus anthocyanins (HAs), a group of natural pigments occurring in the dried flowers of Hibiscus sabdariffa L., were able to quench free radicals from 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl. HAs, at concentrations of 0.10 and 0.20 mg/ml (0.4-0.8 mM), were found to significantly decrease the leakage of lactate dehydrogenase and the formation of malondialdehyde in rat primary hepatocytes induced by a 30-min treatment of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (1.5 mM).12 Wang and Mazza13 demonstrated that common phenolic compounds found in fruits inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in bacterial lipopolysaccharide/interferon-ᵧ-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Anthocyanins/anthocyanidins, including pelargonidin, cyanidin, delphinidin, peonidin, malvidin, malvidin 3-glucoside, and malvidin 3,5-diglucosides in a concentration range of 60 to 500 µM, inhibited NO production by >50% without showing cytotoxicity. However, these concentrations are quite high (3–4 orders of magnitude higher) relative to concentrations measured in plasma.14–17 Anthocyanin-rich crude extracts and concentrates of selected berries were also assayed, and the inhibitory effects of the anthocyanin-rich crude extracts on NO production were significantly correlated with total phenolic and anthocyanin contents.13 Anthocyanins isolated from tart cherries exhibited anti-inflammatory activities as indicated by their ability to inhibit the cyclooxygenase activity of the prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase I.18

The aglycones of the most abundant anthocyanins in food, cyanidin (cy) and delphinidin (dp), were found to inhibit the growth of human tumor cells in vitro in the µM range, whereas malvidin, a typical anthocyanidin in grapes, was less active. However, cyanidin-3-galactoside and malvidin-3-glucoside did not affect tumor cell growth up to 100 µM. The anthocyanidins (cyanidin and delphinidin) were potent inhibitors of the epidermal growth-factor receptor, shutting off downstream signaling cascades.19 Whether these observations have meaning in an in vivo situation is not known, because the aglycones have not been observed in the plasma or urine of humans.

Table 1.2 Anthocyanins distribution (% of total concentration) and content in selected common fruits.a

Anthocyanins and α-Glucosidase Activity

Anthocyanin extracts were found to have potent α-Glucosidase (AGH) inhibitory activity, with an IC(50) value of ~0.35 mg/mL, but anthocyanin extracts did not inhibit sucrase ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CHAPTER 1 ABSORPTION AND METABOLISM OF ANTHOCYANINS: POTENTIAL HEALTH EFFECTS

- CHAPTER 2 COMMON FEATURES IN THE PATHWAYS OF ABSORPTION AND METABOLISM OF FLAVONOIDS

- CHAPTER 3 PHARMACOKINETICS AND BIOAVAILABILITY OF GREEN TEA CATECHINS

- CHAPTER 4 THE IMPORTANCE OF IN VIVO METABOLISM OF POLYPHENOLS AND THEIR BIOLOGICAL ACTIONS

- CHAPTER 5 CANCER PREVENTION BY PHYTOCHEMICALS, MODULATION OF CELL CYCLE

- CHAPTER 6 CANCER CHEMOPREVENTION BY PHYTOPOLYPHENOLS INCLUDING FLAVANOIDS AND FLAVONOIDS THROUGH MODULATING SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION PATHWAYS

- CHAPTER 7 GENE REGULATION BY GLUCOSINOLATE HYDROLYSIS PRODUCTS FROM BROCCOLI

- CHAPTER 8 HEALTHY FOOD VERSUS PHYTOSTEROL-FORTIFIED FOODS FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION OF CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

- CHAPTER 9 VASCULAR EFFECTS OF RESVERATROL

- CHAPTER 10 DEVELOPMENT OF A MIXTURE OF DIETARY CAROTENOIDS AS CANCER CHEMOPREVENTIVE AGENTS: C57BL/6J MICE AS A USEFUL ANIMAL MODEL FOR EFFICACY STUDIES WITH CAROTENOIDS

- CHAPTER 11 CHEMOPREVENTION OF COLON CANCER BY CURCUMIN