- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Viewing The World Ecologically

About this book

During the last 20 years, the American public has become increasingly aware of environmental problems and resource scarcities. This study focuses on the rapid emergence of an ecological social paradigm, which appears to be replacing the technological social paradigm that has dominated American culture throughout most of the 20th century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A New Worldview

Mental Lenses

The world is changing rapidly, but our understanding of these changes, and hence our ability to cope with them, often lags far behind reality. In the past, this has not mattered greatly, as long as the rate of change in our living conditions—technological, economic, environmental, social, and political—remained relatively slow. In those situations, delays in comprehending and responding to emerging trends were not likely to create serious problems in societies. As the rate of change quickens and the scope of change expands to encompass more and more aspects of life, however, it becomes imperative that we be able to comprehend what is happening in the world. To do that, we must open our minds to new ways of viewing and interpreting the human condition in the modern world.

Opening our minds to new ways of viewing and understanding social reality can be a very difficult process, however, since each of us views the world through a firmly entrenched set of mental lenses. These lenses are such a fundamental and familiar part of our perceptual and cognitive abilities that we are usually oblivious to them. We rarely even think about them, let alone question their validity or attempt to change them. Yet without these mental lenses, little of what we observe—either in our personal lives or in the world around us—would make much sense to us. Our mental lenses enable us to integrate our own and others' actions into meaningful patterns, and thus make sense of our shared social experiences.

We use the analogy of "lenses" to describe these entrenched ways of viewing the world to indicate that—like lenses in eye glasses—they are constructed devices, not something we are born with. Like eye glass lenses, they must be carefully ground and polished if we are to see through them clearly. This grinding and polishing of our mental lenses is a continual process, occurring unconsciously through our on-going social experiences and activities. This process begins with our early childhood socialization and is constantly shaped by all the situations we encounter and the roles we enact throughout life. It is also periodically altered by critical events in our lives and in the larger world around us. As long as we live, our mental lenses are always being ground and polished by everything that happens to us. The mental lenses with which we view the world are sometimes called worldviews (which is an approximate translation of the German term Weltanschauung), while at other times they are termed social paradigms. Worldviews and social paradigms are also frequently described as ideologies. There are important distinctions between these three concepts, which we shall explore in the next chapter. For the time being, however, we can simply think of all mental lenses as cognitive, perceptual, and affective maps that we continually use to make sense of the social landscape around us and to find our way to whatever goals we are seeking in life. The principal parts of all such mental lenses are beliefs about the nature of social reality and values concerning desirable and undesirable social conditions.

Because our mental lenses are a fundamental and integral part of our mental processes and shape our innermost thoughts, we often assume that they are our own personal constructs. In reality, however, our mental lenses are essentially collective ideas that we have learned from our culture and share with many other members of our society. Each of us does frame our mental lenses in a personal style, as a consequence of our particular life experiences. But the content and structure of the mental lenses through which we view the world are largely shared cultural ideas.

Every societal culture contains a dominant worldview or social paradigm that is held by most members of that society to some extent, and shapes the major activities of that society. "A dominant social paradigm consisting of common values, beliefs, and shared wisdom about the physical and social environments is essential to any stable society" (Pirages 1977:6). Moreover, a society may also contain one or more alternative worldviews or social paradigms that differ sharply from the prevailing way of thinking. The myriad subcultures held by various sets of people within that society—such as social classes, ethnic groups, and communities—also often proclaim their own more specific ideas about the nature of the world, which may or may not be fully congruent with the dominant societal worldview. And as a consequence of modern mass communications, worldviews and social paradigms frequently cross national boundaries to become international in scope.

Regardless of whether these views of the world are held locally, nationally, or internationally, however, they are always shared sociocultural constructs. In the words of Lester Milbrath (1984:7): "Every organized society has a dominant social paradigm... which consists of the values, metaphysical beliefs, institutions, habits, etc., that collectively provide social lenses through which individuals and groups interpret their social world."

Industrial and Post-Industrial Worldviews

During the past decade, numerous writers have argued that a broad new worldview is emerging in the United States and in other industrial societies. This new way of viewing the world reflects fundamental social changes that are occurring in those societies. Over time, therefore, it will gradually replace the Industrial Worldview which presently dominates all Western nations, and will undoubtedly become the prevailing worldview in future societies.

These writers give a variety of names to the emerging worldview, such as "post-industrial," "new environmental," "sustainable," "voluntary simplicity," and "new age." Despite these differing labels, however, their conceptions of this new worldview are all fairly similar. These conceptions tend to be extremely broad in scope, covering most of the major dimensions of contemporary societies. Moreover, they depict a kind of society that is distinctly different from anything that presently exists. We are entering the dawn of an entirely new social era, these writers insist, which will radically transform both the organization of modern societies and our shared views of the nature of social life.

Rather than sketching each writer's particular conception of this emerging worldview, we have combined all of their ideas into a single composite portrait, which we call the Post-Industrial Worldview. It is drawn primarily from the writings of Gary Coates (1981), Stephen Cotgrove (1982), Duane Elgin (1981), Lester Milbrath (1984), and Daniel Yankelovich (1981), although many other writers have also contributed to this conception of a new worldview. No one of these writers has mentioned all of the elements of our composite Post-Industrial Worldview, but-if pressed-all of them would probably agree with most of its features.

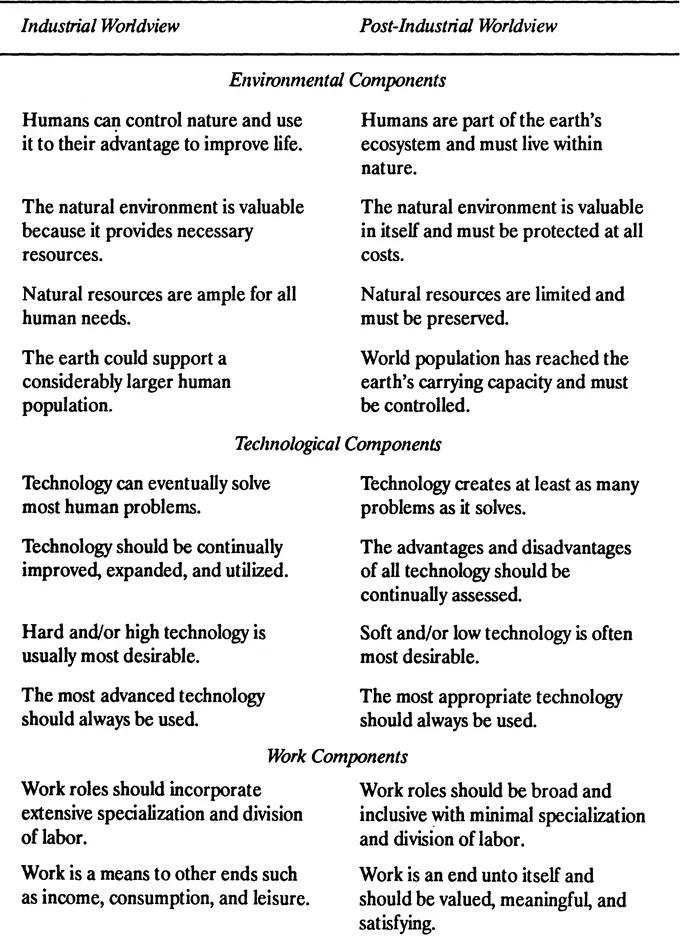

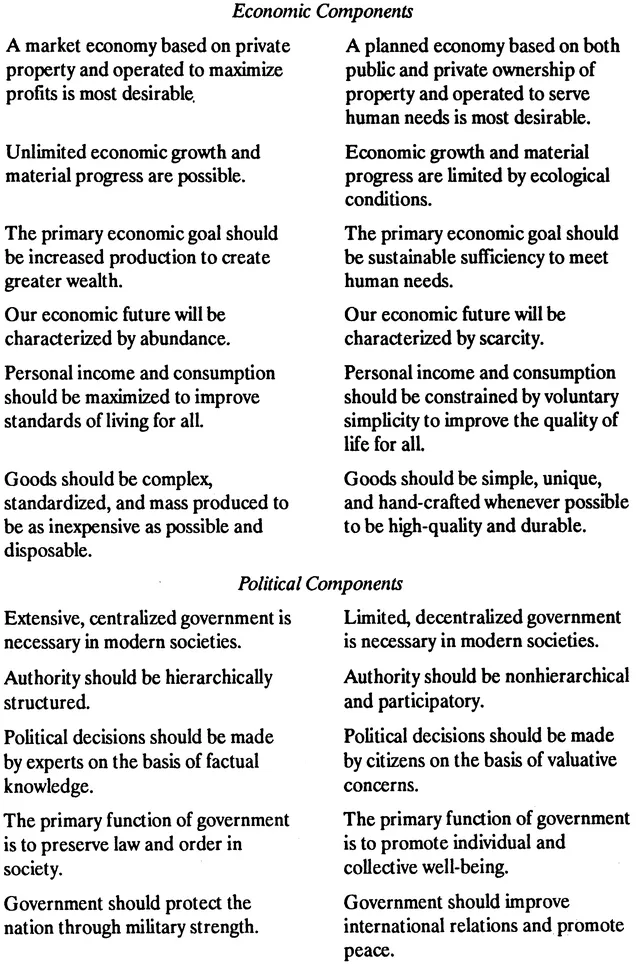

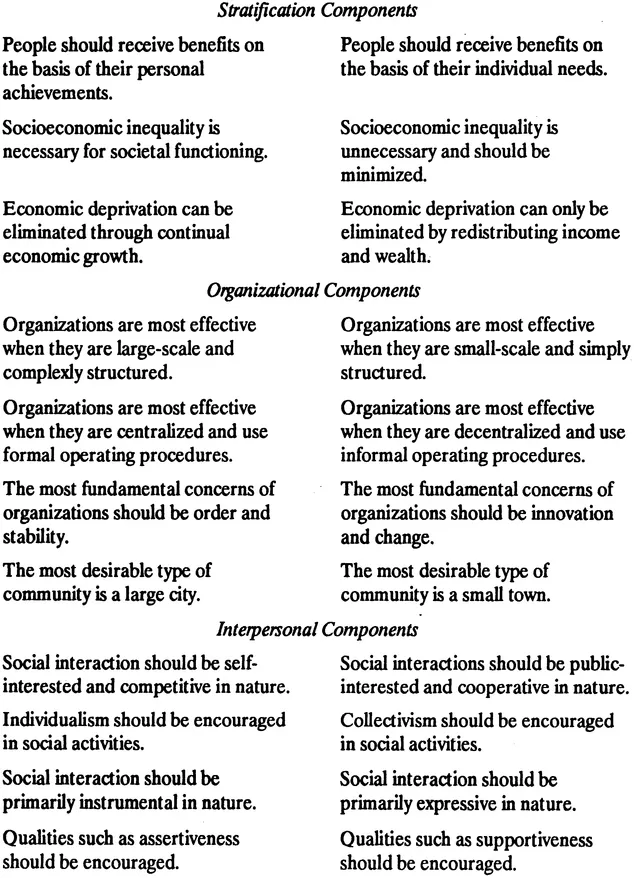

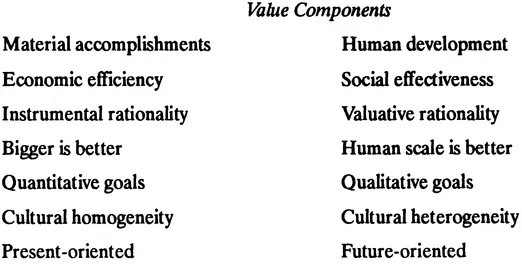

Figure 1.1 lists various components of the old Industrial Worldview in the left-hand column, and corresponding components of the new PostIndustrial Worldview in the right-hand column. These components are arranged under several topical headings, but all of them are commonly viewed as constituting a single, comprehensive conception of human social life.

Three features of these conceptions of the old Industrial Worldview and the new Post-Industrial Worldview in modern societies are particularly noteworthy. First, there is a bias against the old worldview and towards the new worldview. All of these writers tend to believe, to one extent or another, that there are serious problems and deficiencies in contemporary industrial societies that are reflected in the dominant Industrial Worldview. They are therefore convinced that fundamental changes are imperative and desirable in these societies and in their prevailing worldview. Second, there is an implicit assumption that all of the various components of each worldview constitute an integrated and internally consistent entity. Consequently, these writers commonly assume that as some components of the new Post-Industrial Worldview become increasingly prevalent in modern societies, all the other components will inevitably also come to prevail. Third, very little attention has been given in any of these writings to the process of worldview change. What process might produce a shift from the Industrial to the Post-Industrial view of the world?

Research Focus

In this study, we deal with only a portion of the thesis that a broad new worldview is emerging in modern societies. To the extent that such a worldview change is presently occurring, we argue that its "core" consists of environmental/ecological concerns (Buttel 1987; Cotgrove 1982; Dunlap and Van Liere 1978, 1984; Milbarth 1984, 1989). At least since "Earth Day" in 1970 and the publication of The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. 1972) two years later, public awareness of, and concern about, the environmental and ecological problems confronting contemporary industrial societies have steadily expanded (Schnaiberg 1973; Buttel and Flinn 1976; Mitchell 1978; Council on Environmental Quality et al. 1980; Milbrath 1984; Dunlap 1989, 1990; Morrison 1986).

These environmental/ecological concerns take many different forms, including pollution of air and water, disposal of toxic and radioactive wastes, shortages of fossil fuel and minerals, the population explosion

FIGURE 1.1 Components of the Existing Industrial Worldview and the Emerging Post -Industrial Worldview in Modern Societies

and mass starvation, destruction of wild areas, and use of nuclear technologies. Cutting across all these specific concerns, nevertheless, is an emerging public awareness of the fact that human beings are an integral part of the earth's ecosystem, and that modern industrial societies are gradually but inexorably degrading and possibly destroying that ecosystem. Consequently, it is argued, humanity must begin altering our views of the world and our ways of living if modern societies are to endure on a sustainable basis.

Our study therefore assumes that the crucial realm in which to look for the emergence of a new worldview in contemporary societies is in their ecological beliefs and values. We do not assume that a paradigm change in that realm is necessarily—at least at the present time—carry-ing over into other realms of life such as economic and political systems, organizational structures, or interpersonal interaction. We will, however, seek to determine empirically if that is actually happening.

The focus of this research, therefore, is on two fundamental social paradigms in modern societies. The established Technological Social Paradigm presumably lies at the heart of the dominant Industrial Worldview, while an emerging Ecological Social Paradigm is often assumed to constitute the core of a new Post-Industrial Worldview. These concepts of Technological and Ecological Paradigms will be elaborated in subsequent chapters.

The basic thesis of this study is that the prevailing Technological Social Paradigm is gradually being replaced by a radically different Ecological Social Paradigm in modem industrial societies, especially in the United States. To explore that thesis, we address four broad research questions:

- How pervasive are these two social paradigms at the present time?

- How widespread are the Technological and Ecological Social Paradigms among the public?

- What kinds of people hold each of those contrasting social paradigms?

- Do people who hold the new Ecological Social Paradigm also express value and policy preferences which reflect other dimensions of the broad Post-Industrial Worldview sketched in Figure 1.1?

- In what ways and to what extent is the Ecological Social Paradigm related to people's views toward other dimensions of social life, which would indicate that this paradigm is part of a more encompassing Post-Industrial Worldview?

- If the Ecological Social Paradigm is related to people's views concerning several other dimensions of social life, how do they organize those views into clusters that are meaningful to them? And to what extent are those clusters related to the Ecological Social Paradigm?

- To explain the process of paradigm change, can we determine what kinds of factors or conditions are contributing to the emergence of an Ecological Social Paradigm?More specifically, we attempt to clarify Thomas Kuhn's (1970) explanation of paradigm shifts by distinguishing between internal and external causes of this process. He suggests that both types of causes may contribute to paradigm shifts, but his writings do not clearly differentiate them or indicate their relative importance for paradigm shifts.

- Internal causes are logical contradictions within a prevailing social paradigm, so that some beliefs or values within that paradigm are inconsistent with other beliefs or values. We therefore ask if people who hold technological beliefs and also other inconsistent beliefs or values have tended to adopt the Ecological Social Paradigm,

- External causes are perceived discrepancies between a prevailing social paradigm and existing social conditions, so that its beliefs or values are incongruent with those conditions. We therefore ask if people who hold the Technological Social Paradigm and are concerned about the natural environment have also tended to adopt the Ecological Social Paradigm.

- Can paradigm changes best be described as a two-step shift or a three-step dialectic process? More specifically, we ask which of two analytical models more adequately depicts the manner in which paradigms change.

- A paradigm shift model, as developed by Kuhn (1970), is a two-stage discontinuous change process from an old to a new paradigm, in which the new paradigm is unrelated to, and totally different from, the old paradigm.

- A paradigm dialectic model, as suggested by Hegel in 1821 (1942), is a three-stage interactive change process from an existing paradigm to an antithesis paradigm to a synthesis paradigm. The final synthesis paradigm is derived from the original thesis paradigm and the antithesis paradigm and hence contains numerous components of both of them.

Research Design

The data used in this study are taken from a survey of Washington State residents conducted in 1982. The sample for that survey was drawn randomly from all telephone directories for the state, and was intended to represent the total noninstitutionalized adult population of that state with listed telephone numbers. A written questionnaire was mailed to 1,073 potential respondents, with several follow-ups. A total of 696 people returned completed questionnaires, for a response rate of 65 percent. With this many cases, the findings are very likely (at the 95 percent confidence level) to be representative of the total population within an error range of plus or minus 3 percent.

Because the sample was drawn only from the State of Washington, the results cannot be generalized directly to the entire United States. However, an earlier survey that asked a number of the same questions which were included i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- 1 A New Worldview

- 2 Theoretical Framework

- 3 The Technological Social Paradigm

- 4 The Ecological Social Paradigm

- 5 Scope of the Ecological Social Paradigm

- 6 Explaining the Paradigm Change

- 7 Models of Paradigm Change

- 8 Theoretical Arguments

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- References

- About the Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Viewing The World Ecologically by Marvin E. Olsen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.