![]()

PART 1

‘New“ literacies and children's ways of using them

‘New’/different literacies include screen-based literacies, computer texts and games, video games, text messaging, artefacts and toys etc. They embrace new advances in technology, sometimes called digital literacy or technological (techno) literacy, and include a wider, more embracing definition of ‘texts’ to include multimodal texts. These communicate in different ways using visual images, drawings, sounds, words. Even the space we inhabit, gestures, body movements are now being considered as texts. This section contains work with children in relation to some of these ‘new’ literacies.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Multimodal texts

What they are and how children use them

Eve Bearne

Recent developments in digital technology have prompted a reappraisal of just what ‘literacy’ might mean.‘Reading’ now includes more pictures — still and moving — and the routes taken through reading are perhaps more varied than they were.‘Writing’ includes the use of images, diagrams and layout; it is now a matter of design as well as composition. The idea of a ‘text’ is also being redefined; work on multimodal texts reminds us that there are many dimensions to representation and communication. This chapter explores some of these dimensions and considers the classroom demands made by a redefinition of literacy.

Introduction

We live in demanding times. Transformations in communications mean that the landscape of literacy seems altered out of all recognition. This has implications for teaching. Not only do we need to redefine what ‘literacy’ involves, but also to note new uses of the term ‘text’. There is now a vast range of texts available to young readers in different combinations of modes and media so that ‘text’ has come to include not only words-plus-images but moving images, with their associated soundtracks, too. Digital technology has increased the number and type of screen-based texts: 3D animations, websites, DVDs, PlayStation games, hypertextual narratives, chat sites, email, virtual reality representations. Many of these combine words with moving images, sound, colour, a range of photographic, drawn or digitally created visuals; some are interactive, encouraging the reader to compose, represent and communicate through the several dimensions offered by the technology. Not only are there new types of digital texts, however, but a massive proliferation of book and magazine texts which use image, word, page design and typography, often echoing the dimensions of screen-based technology. The availability and familiarity of these texts mean that not only do children bring wider experience of text to the classroom, but their immersion in a multidimensional world means that they think differently, too (Salomon 1998; Brice Heath 2000). This means that the literacy curriculum and pedagogy need to be reshaped to accommodate to shifts in communication and children's text experience.

In considering the demands and challenges of the literacy curriculum in the twenty-first century, there is a pressing imperative to get to grips with the texts, the contexts in which they are used and the language surrounding them (Lankshear & Knobel 2003; Snyder 2003). Part of this means genuinely widening the scope of thinking to include home and family experience of texts. Taking account of home literacy experience means acknowledging that children's preferences in popular cultural forms of reading and viewing out of the classroom are part of their own landscape. In the classroom, however, the teacher selects the texts and ensures that they will come under some kind of critical scrutiny. It is in the classroom that children's literacy is — and ought to be — critically mediated by teachers and others involved in literacy education. I use ‘critically’ in more than one sense: it is, of course, critically important that children have access to their rights in literacy, and that teachers provide for their continuing progress in literacy learning. It is equally important that those rights include the right to read critically and it is essential that teachers take on both senses of the critical as they tackle the literacy curriculum. All of this implies a need to develop new ways of talking about texts — and literacy — and the ways in which they are taught in classrooms. Since many of the new forms of text are encountered outside the classroom, and often at home, talking with children about their own experiences of texts must be part of considering what ‘literacy’ — and specifically critical literacy — might mean in the twenty-first century.

New forms of communication, and the knowledge of texts brought to the classroom by even the very youngest readers, pose new questions for teaching and learning. Many books available in schools now cannot be read by attention to writing alone. Much learning in the curriculum is carried by images, often presented in double-page spreads which are designed to use layout, font size and shape, and colour to complement the information carried by the words. The ‘Dorling Kindersley-type’ book, for example, or the style of magazine pages, both of which are designed as a deliberate combination of words and images, are familiar both inside and outside the classroom. These shifts in the use of layout and image require that we rethink literacy and how it is taught. A central demand is to understand the differences and relationships between the logic of writing, which is governed by time and sequence, and the logic of image, which is governed by space and simultaneity. A story or a piece of information only makes sense if it is read in the intended order, whereas all the features of a picture are available to the viewer at the same time.

Inevitably, new combinations of words and images raise questions about whether literacy learning is the same when it happens through the spatial nature of drawings, pictures or other images, rather than through the linear organisation of letters into words or the sequences of speech. It involves asking:

• What can image offer that words cannot and what can writing (or speech) do that image cannot? And what about the fact that most of the texts in the new communication landscape are multimodal — combining word, image and often sound? There are implications here for classroom approaches to reading and writing and, indeed, for assessments of what progress in reading or writing multimodal texts might involve.

• How can ‘teaching reading’ develop to include all the new types of text that are available? Adults and children alike have a fund of reading experience which seems to be unexplored in many current classroom approaches to reading.

• How does new text experience inform our understanding of children's classroom writing and production of multimodal texts? There are issues about how these are given value, responded to and developed.

In this chapter I want to look at some of the issues raised by trying to tackle these questions and the implications for literacy teaching and learning.

Modes, media and affordances

The first issue — about the different ways that image and word carry meaning — relates to modes of representation: the ways a culture makes meaning through speech, writing, image, gesture, music. Over time, cultures develop regularities, patterns and expectations in any mode(s) of representation. Of course, people use more than one mode to represent ideas. Gesture accompanies speech, and pictures are familiar and established ways of communicating ideas. So it can be argued that texts have always contained multimodal elements or possibilities (Andrews 2001; Bearne 2003; Kress 2003) and that these have been used to engage young learners for centuries. When Comenius composed ‘Orbis Pictus’ in the seventeenth century, he was driven by a conviction that children learn best from the senses and, particularly from the visual (Comenius 1659). The illustrated book (combining the modes of word and image) has long occupied a central place in the education of young readers. Over time, the different technologies available to a community give rise to a range of media for carrying meaning: book, magazine, computer screen, video, film, radio. Current and future combinations of modes and media in their turn make demands on conceptions of literacy.

In terms of communicating meaning, then, there is an issue about what it is possible to do with one mode or another, or with a combination of modes. It is not only a matter of considering what writing affords or allows for ease of communication or, in comparison, what image offers, but also the pedagogic implications of working with children whose text experience is mainly multimodal. Being aware of the different possibilities for meaning offered by multimodal texts means explicitly discussing how texts work to express ideas. This is equally important when considering a whole text or a single page. When reading, for example, what does a printed book afford as compared with watching a text on television? A comparison between a novel and a film can reveal issues of affordance and how the reader/viewer is positioned in relation to the narrative. With a book, the reader can decide to skip descriptive passages, vary the pace of reading and return to earlier pages to check out details or recapture the narrative flow. Although with a video player there is a review and fast forward device, ‘skipping’ is rather more difficult (and disrupts narrative meaning rather more). Similarly, since descriptive detail is part of the visual image, it is almost impossible to ignore the descriptive elements. The film does not ‘afford’ the same reading approach as a book does.

The affordances offered by the different modes and media influence the ways texts are used, returned to, reviewed or reread, and how they are organised and constructed. Different types of text have varying organisational structures, or patterns of cohesion, depending on what the text affords to the reader or viewer. Those that are represented through written narrative or report depend on chronological cohesion so that ideas will be linked by time connectives, for example, then, later, finally. Texts that are represented visually or diagrammatically depend on spatial cohesion using visual links, for example, arrows or simply the juxtapositions of blocks of print and pictures or diagrams. Texts relayed through the medium of sound, the single voice of a radio newsreader, for example, also depend on chronological logic but in addition are made cohesive by repetitions which would be redundant in written texts. Texts that are relayed through physical movement, sound and gesture — plays, ballet, opera — combine both spatial and sound-repetitive cohesive devices but in this case the spatial is three-dimensional. Affordance, then, is dependent on the material of texts and is related to the ways they are constructed.

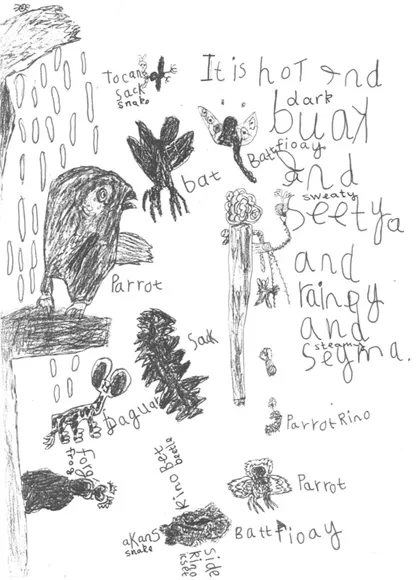

Children's text experience is made up of implicit awareness that it is possible to combine different modes and media to get a message across. Since multimodality is part of children's everyday text experience, there is a pressing issue about the relationship between the kinds of reading and writing fostered in schools and this experience. Particularly, how do we acknowledge and respond to children's increasingly frequent choice of using multimodal texts to represent their meaning? The implications of this question come into clear focus when considering five-year-old Liam's rainforest text (Figure 1.1). The rainforest text was his ‘writing plan’ for a piece of information text. He drew his pictures first then wrote with guidance. The work was cross-curricular, including art and maths as well as drama and literacy, and a classroom display of the rainforest had been established long before the writing began. Leading up to the writing, the class had read simple texts about the Amazonian rainforest and the teacher had discussed how information is presented, specifically looking at how different texts are presented through words and images.1

Figu...