- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pre-Industrial Cities and Technology

About this book

This, the first book in the series, explores cities from the earliest earth built settlements to the dawn of the industrial age exploring ancient, Medieval, early modern and renaissance cities. Among the cities examined are Uruk, Babylon, Thebes, Athens, Rome, Constantinople, Baghdad, Siena, Florence, Antwerp, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Mexico City, Timbuktu, Great Zimbabwe, Hangzhou, Beijing and Hankou Among the technologies discussed are: irrigation, water transport, urban public transport, aqueducts, building materials such as brick and Roman concrete, weaponry and fortifications, street lighting and public clocks.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pre-Industrial Cities and Technology by Colin Chant,David Goodman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

ANCIENT CITIES

Chapter 1: THE NEAR EAST

The author of this chapter is grateful for detailed advice and corrections from Roger Moorey, and for the comments of colleagues at The Open University, including Olwen Williams-Thorpe. The overall approach, however, is the author’s own.

1.1 Introduction

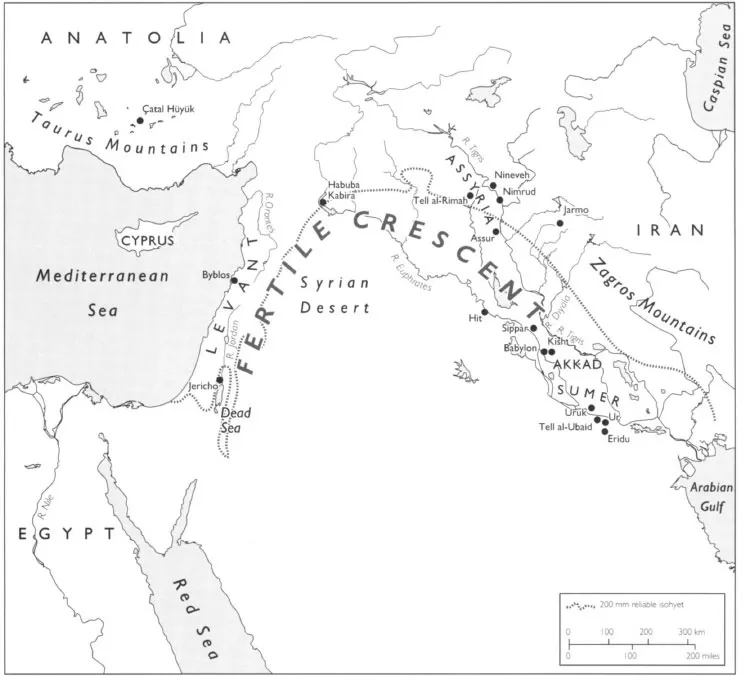

The first settlements of an urban degree of complexity emerged, probably during the late fourth millennium BCE,1 in the Near Eastern region often referred to as the ‘Fertile Crescent’ (see Figure 1.1). An ambiguous geographical term, the Fertile Crescent in its fullest sense denotes the sequence of river valleys and alluvial plains stretching from the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq and eastern Syria), along the Orontes and Jordan in the Levant, to the Nile in Egypt. The trading activity of the first cities stimulated urbanization elsewhere during the later third millennium, notably in the Indus Valley to the east, and in the Mediterranean region to the west – where the first European cities, those of the Minoans and Mycenaeans, developed. This chapter on the Near East, therefore, logically introduces Chapters 2 and 3 on early European urbanization. As one authority on the region has put it, ‘the history of the Western world begins in the Near East, in the Nile Valley and in Mesopotamia, the basin of the Tigris and Euphrates’ (Postgate, 1992, p.xxi).

Figure 1.1 The ancient Near East; north of the isohyet, rainfall was usually at least 200 mm a year – enough to support agriculture without recourse to irrigation

In a chapter dealing with the vicissitudes of urban civilization over more than two millennia, comprehensive coverage is out of the question. Instead, some of the themes of this series of three books are examined through the lens of a period that raises problems of historical interpretation in an acute form. The main difficulty is the fragmentary and uneven nature of the data. Written evidence is available from very soon after the emergence of the first cities, but its survival depends on the materials used and the conditions under which they happen to have been kept. The preservation of artefacts also depends on materials and conditions: biodegradable materials such as wood, textiles and leather survive only in special environments such as waterlogged peatbogs, arid Egyptian tombs and the permafrost of the Altai Mountains; whereas building stones, pottery and glass are eminently durable. But many durable materials, especially precious stones and metals, have been plundered by history’s asset-strippers, from ancient tomb-robbers to modern colonialists, and partly for these reasons the recovery of entire settlements is rare. Another reason is that many important sites have been continuously occupied and developed, and as a result the early history of many of the locations evidently most conducive to urbanization is irretrievably buried.

1.2 The emergence of cities: a technological revolution?

What part has technological innovation played in the development of cities? The simplicity of the question is deceptive: any serious attempt to answer it will require the unravelling of complex historical relationships. An appropriate way to start is to consider the relevance of technological change to the origins of urban settlements. In Section 1.2, the focus is on technological developments arguably necessary for the emergence of urban civilization, rather than those deployed in the process of city-building.

Any introduction to this issue falls under the long shadow cast by the archaeologist V. Gordon Childe (1892–1957), and his concept of a technologically driven ‘Urban Revolution’ in Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium, persuasively presented in Man Makes Himself, first published in 1936. Both his use of the term ‘revolution’, and his privileging of technology in the transition from village to city life, have been challenged ever more vigorously in recent years. However, Childe’s work has been so influential that it must be addressed in any contemporary account of the relations between technology and the emergence of urban society.

The beginnings of technology

Technology is a likely focus for any analysis of changes in human behaviour leading to urbanization, because so much of the prehistoric evidence consists of artefacts. At least two and a half million years before the emergence of cities, early African hominids began with their chipped pebble tools to demonstrate the technological aptitude of the human family – the physical and intellectual capacity to adapt to a given environment by making use of it. This aptitude enabled early humans to colonize diverse environments throughout the Old World (Africa, Europe and Asia). A series of prolonged glacial periods during the later Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) in Europe and Asia encouraged developments in the control of fire, and the use of permanent shelters. These early humans had their domestic technologies – hearths for cooking and heating, and lamps in the form of small stone bowls (presumably fuelled with animal fat). They shaped a variety of tools and weapons, probably from wood but also – as we know from surviving artefacts – from stone and bone; they also developed communication, probably by gestures as well as spoken language. These attributes helped them to supplement their diet by trapping large animals, and also to protect themselves from harsh climates with animal skins. A notable technological extension of human capacities was the augmenting of human muscle power by hunting-weapons such as the spear-thrower (a long rod with a hook at one end) and the bow, described as ‘perhaps the first engine man devised’ (Childe, 1966, p.59).

It is technology that traditionally defines this mind-numbingly protracted ‘Old Stone Age’, but there is also evidence of a burgeoning culture expressed in the representation of daily life (as in the cave paintings at Lascaux in southern France), and the ritual burial of the dead. It seems, then, that it was a blend of technological and social characteristics that enabled small groups, bound by ties of kinship, to survive thousands of millennia by hunting and gathering. Indeed, the successive human species not only survived, but prospered: by the end of the Palaeolithic, Homo sapiens was the ‘only animal with a near-global distribution’, having moved out of the African hominid heartland as far afield as Australia and the Americas (Gamble, 1995, p.1).

In some Palaeolithic habitats unusually well stocked with game and fish (as in central France), there were caves that were settled permanently. On the plains of Russia and central Europe, large camp sites – with some substantial, often semi-subterranean dwellings (pit houses) – were associated with the hunting of herds of mammoth, bison and reindeer. But any sizeable, permanent human settlement was out of the question because the population had to be mobile and, generally, was thinly spread: it has been estimated that in hunter-gatherer societies, population density rarely exceeded one person per ten square kilometres (Morris, 1979, p.3).

Childe’s Neolithic Revolution

For cities to be sustainable, a dramatic change in this ratio had to become possible. The key to this change was agricultural technology. For prehistorians of the Old World, the division between the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) and the Neolithic (New Stone Age) is marked by the transition from the nomadic business of hunting animals and gathering plants in the wild, to the settled occupation of agricultural food-production. The Neolithic began around 9000, as the ice sheets of the most recent Ice Age receded – though, as with all of these technologically defined periods, the timing for a given region varies with the rate of diffusion of the innovations. Moreover, in any such region, the adoption of agriculture was a gradual process, taking place during a period lasting two or three millennia. This transitional period is sometimes identified as the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), and is characterized by innovations in hunting (the domestication of the dog) and fishing (harpoons, nets and paddles). Even where agriculture was fully adopted, not all settlements were permanent (nomadic agriculture is still practised, as in the soil-exhausting slash-and-burn methods of nomadic farmers in the Amazon basin). And even when, after the introduction of irrigation and manuring, permanent plantations became possible, cultivators of plants co-existed with more mobile pastoralists or herdspeople, and nomadic hunters. Periodic tensions and competition for resources between these groups, though often exaggerated by historians, go some way to explain the ebbing and flowing of ancient empires and civilizations.

Despite these qualifications, the invention of agriculture, when viewed against the long Palaeolithic struggle for survival, appears as a radical change in the technological relation between humans and the natural environment. For this reason, as early as the 1920s Childe identified the transition to agriculture, and the relative flood of innovations it seemed to trigger, as a Neolithic Revolution. It was the first of three sets of fundamental change in human history, each consisting of revolutionary innovations in the economic sphere leading to population growth; to follow were the Urban Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. He saw the establishment of cities during the Urban Revolution as driven by the cumulative technological impetus of the Neolithic Revolution, which led to a surplus of food, occupational specialization and the development of trade.

One defining characteristic of agriculture, the basis of Childe’s Neolithic Revolution, was that plants were cultivated on sites of human choosing, and then of human artifice – rather than gathered where they naturally occurred. The creation of plantations was accompanied by the development of implements, such as hoes, sickles and sandstone grain mills. By the fourth millennium, the animal-drawn plough was beginning to replace the hoe as the main tool for cultivation:

Of all the devices created by mankind up to the end of the fourth millennium [BCE] there can be little doubt that the plough had overall the greatest effect. More probably than not it was mainly responsible for the rise in population in the small Mesopotamian and Egyptian cities.

(Hodges, 1971, p.77)

The other main agricultural innovation was the domestication of animals. Goats were tamed in the Near East around 8500, followed by sheep (c.8000), pigs (c.7000) and cattle (c.7000) (Roaf, 1990, p.36). To begin with, such animals were a controllable source of meat, skins and bones, but their captors came to appreciate the value of live animals, first as sources of milk, manure and woollen cloth, and later of motive power replacing humans as drawers of ploughs and carts. These subsequent uses have been called a ‘secondary products revolution’. Placed among the technological developments precipitating Childe’s Urban Revolution, this particular complex of innovations is seen as ‘a major biotechnological shift’, leading to the denser occupation of deserts, steppes and mountains, and in the longer term to urban systems, animal-powered machinery and, eventually, to industrialization (Sherratt, 1981, 1996).

Associated with the establishment of agriculture was the invention of household crafts – notably pottery, carpentry and textile-manufacture. Like agriculture, these crafts involved the manipulation of easily accessible earth, plants and animals to meet human needs. The need both to prepare and to store cereal foods was met by pottery, which replaced containers made of skins, gourds and wood. Making pots was, after cooking, the first human project in practical chemistry: it required knowledge of appropriate mixes and colours of clay, the control of the firing conditions, and skill in applying pigments and varnishes. The seminal principle of the pottery kiln, which may have been established as early as the sixth millennium, was the separation of the vessels from the fire by a perforated clay floor (see Figure 1.2). In the often thickly wooded environments of prehistoric agriculture, timber was a readily available and versatile material, suitable for making tool hafts, ploughs, wheels and houses. Woodworking skills were stimulated by the Neolithic innovation of stone axes (polished with hard, quartz-bearing sandstone), along with adzes, chisels and bow-drills. Another craft associated with mixed farming was the manufacture of woven fabrics of linen or wool for clothing, replacing the hunters’ dressed skins. Textile-manufacture required the invention of spindles and of the loom, ‘one of the great triumphs of human ingenuity’ (Childe, 1966, p.95). Pottery, carpentry and textiles were all crafts which the inhabitants of a self-sufficient agricultural village would practise alongside their often seasonal agricultural tasks. It was not until the rise in productivity associated with the potter’s wheel in the fourth millennium that pottery became the kind of specialized occupation that would characterize urban settlements. The distinction between non-specialized villages and specialized towns and cities, however, can be exaggerated: there is some evidence from northern Mesopotamia of interdependence and specialization among villages, at least one of which may have been a community of hunters and tanners processing onagers, or wild asses (Moorey, 1994, p.2).

Where did the transition to agriculture take place? It is important to recognize that agriculture and its related crafts, and the urban civilizations which followed, must ha...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1 Ancient Cities

- Part 2 Medieval And Early Modern Cites

- Part 3 Pre-Industrial Cities in China and Africa

- Index

- Acknowledgements