2

Rewinding the Tape: Starting Anew

Date of Birth: 10 April 1928

Berit Ås

Professor Emeritus and former President of the Feminist University, Norway, and former Professor of Psychology, University of Oslo, Norway

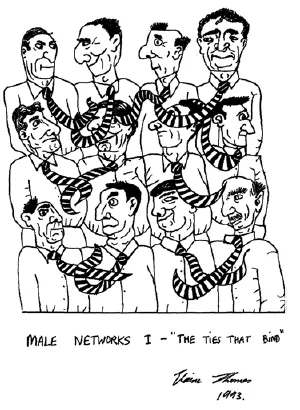

I am leafing through a series of recent profiles of me in some Swedish and Norwegian papers. I am a Norwegian, with all the personality traits generally attributed to members of my society: confident, competitive, highly moral, empathetic and kind (Jonassen, 1983). But it is in Sweden that I feel like an internationally known celebrity, because five years ago a Swedish community of 7000 inhabitants, the community of Växjö, asked their Committee for Equal Rights Between the Sexes to produce an educational video about my theory of body language. This is a theory about how a dominant group can use wordless signals and symbols to suppress, intimidate and harass members of a subordinate group. (To construct middle range social theories has, throughout my life, been my greatest challenge!) I was awarded an honorary degree for this theoretical work at the University of Copenhagen in 1991. The title of the video is The Five Master Suppression Techniques: A Theory About the Language of Power (Växjö, 1992), and it has been written up in different forms in at least twelve languages, including Chinese, Tibetan and Sami (formerly Lapp). It is used in many leadership training courses in both Denmark and Sweden, because it shows how men use their body language to suppress women. It has also been translated into English. Considering the long time necessary to develop this ‘therapeutic theory’ that it required more than twenty years to do the observation and analysis and to write it up, the video producer who clipped and edited my many hours of lectures into a video of twenty-nine minutes was, indeed, a professional genius. The challenge to write my own biography in just a few pages intrigues me. I feel just like this producer.

Travelling Forwards; Looking Backwards

Now, today, I am travelling by a fast inter-city train heading for the Feminist University in Norway; a special educational institution which I set up in 1983. I realize as I observe the beauty of the autumn colours in the woods and fields outside my window that I am, indeed, 68-years-old or, to be more exact, 68 and six months. That amounts to about 18,000 days and around 400,000 hours, of which a third has been spent asleep. So tell me: how do I select from among those days and hours the events which give the most accurate picture of my life’s exceptionally rich opportunities? And of the ingenious structural and cultural resistance to feminists’ attempts to change my patriarchal society for the better? My train travels fast. When I reflect about my experiences, I realize that I should draw on my training in advanced statistics and methodology at the University of Michigan’s doctoral program as long ago as 1959–60. As a mother of four, I was told that the Board of the Institute for Psychology had been very doubtful about accepting me. I had won the American University Association of Women’s Scholarship. That counted positively. My grades from the University of Oslo were good. But a young mother of four? It would have been different, of course, had I been a father of four! The Institute had a rule which they had been following for a while: to admit three women for every seven male students with degree results of a similar standard. I found this a shocking state of affairs when I first heard about it, especially as the reason given was that the Institute needed scholars who in the future would become famous social scientists, an outcome which could not be expected from female students since they would gradually disappear from their jobs to have babies and take on family responsibilities. This was certainly a pre-Friedan society, implementing the patriarchal rule: ‘Keep them barefoot and pregnant to support the US economy by bringing new consumers into the market!’ But the quota argument had such an impact on me that I remembered it clearly when I later became an elected party leader in 1973 back in Norway. Then I demanded new rules including a quota system which would guarantee at least 40 per cent representation by women at every level of the party’s organization. This was possibly the first set of regulations of this kind in the world of politics (see Ås, 1984).

As a scholar I should be able to do the selection samples, especially since for most of my professional life as a lecturer, as an assistant professor and then as a full professor, I taught research methods in social psychology. From 1968 until 1994 I was employed by the Institute for Psychology at Oslo University, teaching social psychology. It included teaching applied social science, especially consumer behaviour and accident research, areas in which I have developed my professorial competencies. In 1988 the ability to implement research findings won me the international Bernardijn ten Zeldam Prize in the Netherlands. The lecture which I was asked to give in the Nieuwe Kirk in Amsterdam was called ‘Managing visions from invisibility to visibility: Women’s impact in the nineties’ (Ås, 1988). My work has certainly included the technique of selecting samples. So what to choose? How to proceed? What to select? Some years ago I was asked to take stock of my achievements as a politician, feminist and professor for the tenth anniversary edition of our research journal for women’s studies. I did. Counting initiatives for which I had invested sometimes years, sometimes months, I found that I could count eight successes and thirty-two failures; a success rate of more than 20 per cent. I should add, however, that at least half the fiascos would not have turned out badly if I had been initiated by a man: a male scholar, a male politician or a male organizer. Somehow I felt quite good about this success rate, especially when I realized that many of my initiatives and suggestions had been picked up, taken further, and accomplished, years after I counted them as failures. My conclusion at the time of writing that piece, which became its title of that paper, was: ‘If you are not ahead of your time, your time will never arrive.’

Summing up: as a person of 68, I am now entering my third year of retirement. I left my job as a social scientist and professor of social psychology because the conventional education system in the university did not allow time to teach what I found most important in our old suffering world, namely: recent scholarship in women’s studies and a feminist critique of methods and theories in most disciplines (Ås, 1985, reprinted 1989); and also how ecological problems influence our lives, and damage women’s and children’s lives more than men’s, in both the developed and developing countries. Imagine what consequences we would document and foresee if we worked from the assumption that a strong, enduring but invisible female culture existed everywhere! (see Ås, 1975). I wanted to teach peace studies and to direct research on conflict resolution and non-violent actions (Ås, 1982). My strong motivation for this stemmed without doubt from my childhood war-time experiences, from my father’s absence when he was in a concentration camp, and later from the influence of my American friends who worked in the peace movement.

Through my twenty-six years of teaching at the University of Oslo, I have been invited to different foreign universities as a visiting professor: to the University of Missouri, Columbia, USA (1965–66), to Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, Canada, (autumn 1981) and the University of Uppsala, Sweden (autumn 1989). The frustration I have felt during my career finally provoked, in 1976, the idea of building a feminist university. As time went by, this idea became almost an obsession. The impetus came from not being allowed to teach women’s studies, reinforced by my strong belief that the way we have constructed our current knowledge base in our Western white male world is pointless. Strict disciplinary boundaries and the fragmentation of science, the lack of truly relevant knowledge and the exclusion of feminist theorization from mainstream work have brought about the present situation. We need to reorganize our disciplines and to integrate recent important research findings into a new knowledge base. My visits to forty universities around the world strengthened my conviction that the common include inheritance from the Middle Ages on which most universities have been built is now obsolete (Ås, 1990). In searching for this invisible female culture and a new knowledge base, I also visited groups of indigenous people, as well as religious and feminist groups. The construction of this knowledge base, as well as numerous critiques of patriarchal paradigms in science by feminist scholars, led to a plan for opening the Feminist University in Norway in 1985.

During eight of the twelve years for which the institution has existed, I have functioned as the President of the Board. One of my main motives for continuing this work has been the need for women’s education. This was strengthened by the findings of a research project which I directed during the 1970s to map women’s needs for adult education in a large county in Norway.

I am a retired university professor. I have just been visiting and teaching at the Feminist University at Loten. In their library I was reminded of all the articles, projects and applications for funds which I have written during recent years to try to secure financial support for teaching about research in women’s studies to those women who can use this knowledge in their daily lives. I am back on my express train again heading for home.

Five Decisions on a Parallel Track

We stop. The train is reversing into a parallel track. The attendant explains that this is necessary to let a faster train pass. It reminds me that I myself have travelled on many parallel tracks! Indeed, some of my experiences in public life between 1960 and 1980 need to be included on the tape. I had better use this quiet stop to mention events from my political life, my participation in the women’s peace movement and my community activities. Returning from Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1960, where I had done my postgraduate work and my husband did his research in industrial sociology, I had five important decisions to make. The first concerned my own research. As I wanted to start my research career, I applied to the National Research Council for funding for a study of ‘the female society’, and received a clear-cut answer that what I wanted to do was ‘women’s lib’ and not proper social science research. If, however, I would consider doing accident research, I was obviously qualified for that, and they were willing to provide me with financial support. I accepted and undertook my first comprehensive study on ‘Accidents and sex roles’ (Ås, 1962).

This was to have an important influence on my community work, as no traffic safety arrangements existed, in spite of a rapid growth in private car ownership and a frightening increase in the numbers of road accident victims. I decided to work with politicians, parents’ organizations, and planning authorities, which brought me into political activism and taught me that I had to become politically active in order to be able to plan and rebuild the road infrastructure in my community. Since three Norwegian political parties sought to recruit me, I accepted an invitation to join the most welfare-oriented of them, Labour, for which I entered the local Community Council in Asker in 1967.

My second decision involved working with other women. The male members of the forty-seven-strong Council wanted to give top priority to building new main roads and to promoting the use of private cars, while the women members, especially those who were mothers, were arguing strongly for better planned traffic safety. We came to see that, without a majority of women on the Community Council, no road safety measures would ever be introduced. In the election of new members in 1971 I took part in a national campaign which brought about a majority of women on our Council, and resulted in a majority of women in two city councils, Oslo and Trondheim. From this experience and from my new position as Deputy Mayor in Asker, I could clearly observe sex-stereotyped interests in political issues. That decided my fate in politics: I became convinced that women must be considered the new proletariat, to whose interests few mainstream politicians are willing to give priority within our conventional party systems. I became a feminist politician.

Thirdly, I returned from the US in 1960 deeply affected by a meeting there with the Norwegian-born Elise Boulding in Ann Arbor. She was a peace research person, a Quaker as well as a leader of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in her country. Having had the opportunity to observe how she worked in community activism as well as academically, I became and was for many years involved in the Norwegian Branch of WISP (Women’s International Strike for Peace), which I started. Her World History of Women fascinated me and inspired my long years as an activist and research worker on women’s peace organizations and women’s social and economic development (Ås, 1981).

Fourthly, my stipend to go to the US was funded by the International Federation of University Women (IFUW). I had been a student member of that organization. Now I wanted to pay my dues for the opportunity which this organization had given me. I became first the leader of its Oslo Branch, then later I was for many years its national leader. As such, I became well acquainted with women’s difficulties in academia, both as young student mothers and as competitors with men for stipends and academic positions. In 1951, when my first child was born, I initiated and was a member of the first student committee to build a nursery and day care institution on the Oslo University campus. Most important, however, was my awakened interest in how women in our society could be given opportunities to educate themselves in adult life. I felt it necessary to initiate a research project, which I have already mentioned, to establish the barriers met by women who want to educate themselves as adults. Three students graduated with research degrees on the basis of this project, writing their theses on different aspects of the data collected.

Finally, as the fifth challenge came the political work. In 1966 I decided to join a political party and chose the Labour Party of Norway. My main reason for doing so was to rebuild the community in which my family lived, so that I could implement the results of my research into accidents and my specialist knowledge of road safety measures. This brought me further into political activity until I ended up as Deputy Mayor in my own local community council. During the heated debate about Norway’s possible membership of the European Union in the early 1970s, I took a stand against membership and organized women from all parties into a united protest front. After the referendum, in which then, as now in the latest referendum, women’s votes had an important effect and resulted in Norway staying outside the European Union, the Labour Party leadership was very angry with me. To punish me they excluded me from the nomination process to our Parliament, the Storting. They invited me, however, to rejoin the party after the nomination process was over and they had successfully prevented me from being nominated as a parliamentary candidate by my own county. A very interesting and supportive book has been written about my suspension and this party struggle (Winther, 1973).

To cut a long story short: when I was offered the chance to rejoin the party after the nomination process was over, I left Labour to form a new socialist party called the Democratic Socialists (AIK). It was mostly older men from the strong steel union who encouraged me to become Norway’s first female party leader and to organize a party somewhat to the left of the Labour Party which has gradually changed, moving to the right as most Social Democratic parties do as they ‘mature’. During the spring of 1973 an Election Alliance was formed, in which my party participated. It won sixteen seats of a total of 155 seats in the Norwegian Parliament. I entered the Parliament as a party leader and was later elected leader of the Socialist Left Party in 1975, when the election alliance wanted to become a more coherent group. The quota rule was included in the party’s regulations from the beginning.

For some years my position as a politician necessarily led to a less central role as a researcher and university teacher. This period lasted from 1973 to 1981. During these years I worked as a parliamentarian, as a party leader, a UN representative, and a member of the government’s Committee for Foreign Affairs and Constitutional Questions, where I finally proposed a change in the Constitution to guarantee a fair representation for both sexes: a 50:50 per cent representation of men and women in our Parliament. I lost, of course, but the issue had been introduced and it has influenced most of the parties in Norway in favour of including a quota rule in their regulations.

Who am I? I am rewinding my tape. The inter-city train starts running again. I am on my way home and I recapitulate my journey: I am 68 and enjoy teaching and organizing as never before. I teach from what I have read and learned during my life as an academic, a feminist and a politician. At 63 and 60 years old I received my honorary degrees in Halifax and Copenhagen and an international prize in Amsterdam. In 1983, when I founded the Feminist University, I was 55-years-old, but I had thought about it a great deal from the end of the UN Women’s Year Congress in Mexico City in 1975. In 1973 when I was 45 and a Deputy Mayor in my community, I was suspended from my party and I organized a new party. At that time I directed a study (lasting from 1972 to 1979) on the barriers facing women who want to take up adult education and paid work. When I was 38 I entered party politics to rebuild the roads in my community and to participate in decision-making about road safety, consumer economics and single mothers. I was 33-years-old when I organized the Norwegian Branch of WISP, becoming involved with opposition to the Vietnam war, the protest against atomic weapons and theoretical work on military strategy, peace and conflict. At 32 I first held office in the International Federation of University Women. I have been working continuously from 1953, when I graduated from university. My fourth child was born when I was 29.

How funny! 29 years is the age I always have been. When I was a teenager, I felt so much older than my peers. As a serious young woman opposed to the German occupation of Norway during the Second World War, I felt sorrow and pity for the children of the Nazis. How could they understand what they were doing? In the dying days of the war I suffered as I observed the young boys of 15 and 16 years of age, called up to serve during Germany’s last days. I suffered when I learned about the way the Russian and Yugoslavian prisoners were treated in the German concentration camps. The Jewish tragedy made me weep for the dead and tortured. Today, as for the last twenty years, I have been crying for the Palestinians.

We have recently been through a war of the most horrible kind in Bosnia. All over the world so-called civilized countries have manufactured and profited from the sale of land mines. Today a million refugees from Ruanda are on the run. Without food or water, mothers are leaving their dying children behind. I have seen much, but at 29 I feel as helpless as a child. Nations and banks are building dams all over the world, from which we earn our money in Norway: we are the experts on hydroelectric power. In the northern part of Namibia we are damming again to put under water the fields and woods where 20,000 indigenous people live. As a 29-year-old woman I may be responsible and hard-working in my own neighbourhood, but without the slightest influence on the world events which are planned and implemented by grown-up politicians.

As the most natural thing we maim and sell children to be used by adult men for pleasure. Wives are abused and killed. Boys are taught how to become heroes, but end up as criminals. Give me a thousand years of wisdom. And let me, as a 29-year-old, cling to my hopes for a better world!

Childhood Experiences

I am rewinding the tape until I can start it from the beginning. My life is like a tape. How come all this happened to me? What factors account for my successes and failures? My upbringing? My sex category? My playmates—only boys, who mostly laughed at me and my ideas—and have, to a certain extent, continued to laugh as mighty grown-ups. My intelligent and supportive spouse? Parents who encouraged me to think for myself, although they sometimes forgot their own advice and tried to push me back towards a more conventional path? A mother who was a teacher and painter, poet and organizer. A father who had wanted to become an inventor, and who successfully invented the most useful and odd gadgets for home use, in addition to inventions which he could not afford to put into production. For instance, magnetizing steel under low temperature, as early as 1933. That my parents fitted into a sociological theory about upward mobility, and therefore motivated their children to aim for university degrees? And I am...