![]()

Part I

Gendered access and experience of ICTs and the Internet

![]()

Chapter 1

Women and the Internet

The natural history of a research project

Anne Scott, Lesley Semmens and Lynette Willoughby

Abstract

This chapter represents a narrative, ‘women and the Internet’, as a women and technology origin story with a fixed beginning, a contested centre and an open ending. This chapter analyses our engagement with this narrative as a pilot study was conducted to look at women’s perceptions of, and relationships to, the Internet. Although this story felt like a coherent and persuasive narrative, this was questioned as the outcomes of the pilot study were reflected upon. Women coming to the ‘Net’ led to a reconstruction of the questions that need to be addressed in researching gender and information technology. This chapter begins by describing and deconstructing the motivating story that was brought to this research project. Three genres are introduced – ‘the webbed Utopia’, ‘flamed out’ and ‘locked into locality’ – which are seen as forming the contested centre of this narrative. While each genre has its own narrative logic, all of them draw on a common tale of historical origins. From each of these perspectives ‘women and the Internet’ has an ending which is still open, but is rapidly closing.

Three questions are then identified which have been raised by analysis: what do we mean by ‘access’?, what do we mean by ‘the Internet’? and ‘which women’? The seeming simplicity of these questions disguises serious difficulties which research in this area must address.

Introduction

We are three academics – a software engineer, a social scientist, and a microprocessor engineer – in the early stages of a research project on women’s relationship to the Internet. We wish to explore means of increasing the access of ordinary women to some of the most powerful of the new communication and information technologies (ICTs). We also wish to discern why previous efforts to improve women’s ICT access have been less than successful. We are feminists, and all three members of our group have a history of involvement in projects to improve women’s access to technology, to education and to social power.

This chapter is a reflection on the pilot stage of our questionnaire-based study. It was expected that the pilot study would generate, primarily, methodological refinements and empirical data, but the results presented a rather unexpected set of outcomes. Rather than generating answers, it was found that the study was generating questions. In analysing the preliminary results, we began to reflect on the assumptions we had brought to this project, and on the way these assumptions are embedded in a story which is becoming established as the feminist account of women’s relationship to the Internet and other new ICTs. This narrative then became the primary focus of our attention.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that the ‘facts’ for which we were looking could not be disentangled from a narrative in which we were deeply, if rather unreflexively, embedded. Feminist epistemologists have established that all knowledge, including our own, must be contextualized (Lloyd 1984; Harding 1991; Alcoff and Potter 1993; Code 1995). As Haraway has noted:

the life and social sciences … are story-laden; these sciences are composed through complex, historically specific storytelling practices. Facts are theory-laden; theories are value-laden; values are storyladen. Therefore, facts are meaningful within stories.

(Haraway 1986: 79)

In this chapter, we would like to begin describing and deconstructing the political and academic story – a story we have entitled ‘women and the Internet’ – that we brought to this research project. We believe that this story has become familiar to feminists with an interest in gender and information technology; it is becoming – to borrow another of Haraway’s terms – an ‘origin story’ (Haraway 1986). We will be representing ‘women and the Internet’ as a story with a fixed beginning, a contested centre and an open ending. It was an engagement with this origin story that catalysed our research interests and that informed our questionnaire design in the study’s pilot phase. A lack of firm results then inaugurated a process of reflection that has highlighted the discursive construction of that story. It is these reflections, and the consequent rethinking of ‘women and the Internet’ as a narrative, that will be the subject of the rest of this chapter.

Women and the Internet – a women-and-technology origin story

A near-consensual beginning

‘Women and the Internet’ is a story that – notwithstanding a few feminist attempts to highlight the nineteenth century activities of Ada Lovelace (Toole 1996; Plant 1997a) – generally begins with the military–industrial complex. Numerous histories describe the development of the first computers during the Second World War to crack enemy codes and to calculate missile trajectories. Large mainframes later began to be used for scientific research and in business for payroll and databases. The linked network now known as the Internet is also described as having had its origins in the US military (Quarterman 1993; Panos 1995; Salus 1995). During the early days of the space race the US Department of Defense created the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Part of ARPA’s remit was to improve US military communications and, in 1969, four ARPANET computers were connected; these four nodes constituted the origin of the Internet.

Supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the US (Loader 1997: 6), academics and industrialists began connecting to the network. By the time NSF support ended in 1995, the commercial potential of the Internet in the form of the World Wide Web was beginning to be realized, and the Internet had emerged as a globalized communication system (Harasim 1993a; Castells 1996). It was catalysing new means of engaging in politics (Schuler 1996; Wittig and Schmitz 1996; Castells 1997; Tsagarousianou et al. 1998), of constructing identity (Stone 1995; Turkle 1995), of managing business, and of organizing criminal networks (Castells 1996, 1998; Rathmell 1998). Within the feminist tale of its origins, this world-changing technology has been said to have had its origins in a male world with four roots: the military, the academy, engineering and industry (Harvey 1997). Differing versions of this historical account have been used to underpin analyses of the exclusion of women and other minority groups from the Internet via, for example, search engine operation, Internet culture and the netiquette which governs acceptable online behaviour (Spender 1995; Wylie 1995; Harvey 1997; Holderness 1998; Morahan-Martin 1998).

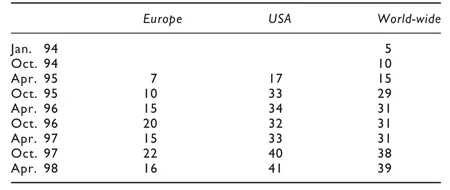

Table 1.1 Women as percentage of users (GVU 1994–8)

Empirical surveys have consistently suggested that women are underrepresented as users of the Internet. The numbers worldwide using the Internet have been regularly surveyed by the Graphics, Visualization and Usability Centre, Georgia Tech University (GVU) (GVU 1994–8). Table 1.1 shows the percentages of women participants over the period from January 1994 to April 1998. The early figures show a very low participation rate that rose, stabilized at about 30 per cent, and is now rising again. The US has the highest numbers of women on the Internet; European women, by contrast, represent only between 15 per cent and 25 per cent of Internet users while, according to Morahan-Martin (1998: 3), only 5 per cent of Japanese and Middle Eastern Internet users are female. Other surveys have tried to get a picture of the ‘average’ user. Which?, in its 1998 annual Internet survey, claimed that UK users have a distinct profile: ‘They tend to be male, under 35, living in the south, more affluent, employed, with no children living in the household’ (Which? 1998). This data has played a pivotal role in grounding this tale of women’s relative exclusion from the electronic networks.

While ‘women and the Internet’ has had a wide variety of retellings, the themes noted here tend to make repeated appearances. The resulting narrative has acted as a coherent and motivating origin story for feminists with an interest in the new information and communication technologies. In it, these technologies – with enormous potential to diffuse information more widely, to increase democracy, to overturn the modernist conception of the sovereign (male) individual, and to improve women’s everyday lives – seem to have been misused, misappropriated and squandered. The point that the ICTs are reinforcing the very inequalities they should be combating is hammered home. As Spender argues in her influential Nattering on the Net (1995), the ICTs represent the new literacy, therefore many women are being rendered as twenty-first century illiterates.

What should be done?

As noted in the introduction, we have been thoroughly immersed in this story. As feminists committed to democracy and to women’s full inclusion in the contemporary socio-technological revolution, we have been involved in practical efforts to change this situation. Two of the authors have done a series of conference presentations on women’s exclusion from the Internet, described as ‘a white male playground’ (Semmens and Willoughby 1996). We have written about the increasing privatization of the electronic networks (Scott 1998a), noting the fact that – as military funding has dried up – they have been increasingly orientated towards the interests of commerce and the private sector. We have all been involved in efforts to develop more women-friendly forms of ICT education.1 We have put our energies into these projects in the belief that, without positive action by interested feminists, the electronic networks will soon be, as Wylie put it, ‘no place for women’ (1995).

Like others working in this area, we have used actor network theory and social constructionist analyses of technology to argue that technological development is, in itself, a social process; it is an endogenous part of the wider development of society. The shape of technological artefacts is, in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways, influenced by cultural expectations, legal frameworks, institutional imperatives, global finance markets, implicit models of potential users, and social beliefs (Cockburn and Ormrod 1993; Akrich 1995; Franklin 1997; Pool 1997). Historically, if new technologies are to gain acceptance they must, in some way, have acted to construct a social and cultural context in which they ‘make sense’, and in which they are needed (Callon 1991; Cockburn and Ormrod 1993; Latour 1993).2 Thus, to be successful, new technologies must be produced in conjunction with new social practices, new social forms and new social networks which are able to receive and utilize them. We have been committed to the construction of new socio-technical practices which are as gender-sensitive as possible.

As interrelationships between the actors developing the ‘information society’ become denser and more complex, the shape of the new actor network developing around the ICTs (Callon 1991; Latour 1993) will become less malleable and less reversible; a new techno-social reality will have been created:

A fact is born in a laboratory, becomes stripped of its contingency and the process of its production to appear in its facticity as Truth. Some Truths and technologies, joined in networks of translation, become enormously stable features of our landscape, shaping action and inhibiting certain kinds of change.

(Star 1991: 40)

If women do not ‘fit’ well within the new technological standards now developing, they will find themselves being marginalized within developing social practices and social forms. As Haraway has noted, ‘not fitting a standard is not the same thing as existing in a world without that standard’ (1997: 37–8). The gender and ICT problem thus seems to be an urgent one; once this new socio-technical reality has become firmly established, people who fail to fit well within it must either adapt to it or accept marginalization.

‘Women and the Internet’, as a narrative, is thus a story suffused with anxiety. New technological standards, protocols, products and structures are being developed at an incredible speed. New legal frameworks, social practices, economic models, organizational structures, institutional forms, cultural traditions, educational practices and forms of discourse are emerging to provide a context for them (Castells 1996; Hills and Michalis 1997; Loader 1997; Agre 1998). The process of development currently underway will thus have direct and far-reaching material consequences. Like many other feminists working within this area, we have seen it as imperative that women are not excluded from full involvement in the design, use and adaptation of the ICTs during this formative phase of their development.

So this story forms a context in which we believe it important to learn why women seem to be relatively excluded from the electronic networks. It was decided that we needed to ask women themselves how they felt about the Internet, about their preconceptions and, after trying the net for themselves, their perceptions. This was the starting place for the pilot study ‘Women coming to the Net’, in which women attending short courses on the Internet or related subject areas were asked to complete a questionnaire. The shape of the pilot study drew heavily on a bid to the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) virtual society programme, which had been submitted earlier by two of the authors.

Story? Which story?

While ‘women and the Internet’ opens in a reasonably cohesive fashion, this feminist tale then splits into at least three, semi-competing, versions.3 At the risk of over-simplifying and caricaturing a very complex literature, we might designate these accounts as: ‘the webbed Utopia’; ‘flamed out’; and ‘locked into locality’.

These three versions of the ‘women and the Internet’ narrative differ sharply in the way they perceive women’s relationship with the Internet. They range from an optimistic celebration of women’s subversive activity via the electronic networks to tales of exclusion, harassment and violence. Indeed, these competing stories might be said to belong to different genres entirely.

Account one: ‘the webbed Utopia’

Drawing on examples such as the famous case of the PEN network in Santa Monica (Wittig and Schmitz 1996), Light argues that the electronic networks offer women new possibilities for networking and for participative democracy. She insists that this vision is not ‘a feminist Utopia like the science fiction worlds of scholars such as Sally Miller Gearhart (1983). Rather, it is realistic and practical; at its core is the concept of seizing control of a new communications technology’ (Light 1995: 133).

Whether or not Light’s assessment of practicality can carry the tale ‘Women and the Internet’ all the way to its conclusion, she has correctly identified her genre. ‘The webbed Utopia’ is heavily influenced by the recent flood of feminist science fiction and fantasy. Sadie Plant, for example, recently stated that the ‘doom’ of patriarchy is inevitable, and that it ‘manifests itself as an alien invasion, a program which is already running beyond the human’ (1997b: 503).

The optimism of the webbed Utopians has been reinforced by a number of contemporary examples in which activists have successfully employed the Internet for political ends. Systers, cyber-grrls and other feminist networks, for example, have worked to open up women-friendly spaces on the electronic networks (Camp 1996; Wakeford 1997). Political networking – primarily via email – was successful in influencing the outcome of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing; the campaign influenced both the conference’s primary agend...