![]()

1

THE BRIEF LIFE AND PROTRACTED DEATH OF ROCK & ROLL

They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.

—Pozzo, Waiting for Godot

The history of modern art, in whatever genre we might wish to examine, is (or imagines itself to be) a history of outrages: a chronicle of insults done to the reigning style in the name of “the new,” and the greater mimetic or expressive potential of the art form. In fiction, for instance, the genial omniscient Narrator of the Victorian novel is replaced with the limited, unreliable first-person narrator so prevalent in modernist fiction; we end up with psychic wrecks like Charlie Marlow (Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) and John Dowell (Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier), and narcissistic poseurs like Stephen Dedalus (James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)—and the “gentle reader” used to the guiding hand of a Charles Dickens or a George Eliot feels utterly alone: abandoned in the Congo mists rather than nimbly led through the London fog. Thus does modernist narrative experimentation “kill off” the well-made Victorian triple-decker. After the outrages of Henry James, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, and Gertrude Stein, the nineteenth-century novel is left for dead.

In the visual arts, the Salon des Refusés kills off the Paris Salon, just as surely as Duchamp puts an end to certain notions of the artist as godlike ab nihilo Creator; in Stravinsky and Diaghilev’s Le Sacré du printemps, it is the classical ballet tradition that is sacrificed, much as T.S. Eliot, in the words of an admiring James Joyce, “ended the idea of poetry for ladies” by publishing The Waste Land.1 In each of these instances—and many more like them—art history now records that something important was struggling to be born; but contemporary reaction more frequently believed that something irreplaceable was dying, was being killed. In the modern era, the birth of new art is always greeted by the cry that “art is dead.”

Nowhere is this more obviously the case than in popular music. In June 1929, the Paris-based bilingual arts magazine Tambour ran an album review under the title “MORT DU JAZZ?” because the slight fare issuing forth from American jazz labels suggested to the reviewer that jazz had run its course. When Bob Dylan, famously, plugged in his electric guitar at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, traditional music fans imagined him swinging his axe at the very root of what we would now call roots music.2 Muddy Waters similarly muddied the pristine waters of the blues when he moved up to Chicago and transformed his sound from acoustic to electric, from rural South to urban North. Even classical music is improbably believed by some traditionalists to have died, a topic pursued in Norman Lebrecht’s 1996 book, first published with the sensationalistic title When the Music Stops: Managers, Maestros, and the Corporate Murder of Classical Music and then issued in paperback under the more generic name Who Killed Classical Music?. More recently, New York Times music critic Joseph Horowitz published a new book with the symptomatic title Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall. Popular music, it seems, has always already been dying.

It’s amazing, when you stop to look at it, how many still vital, still evolving art forms have been declared dead over the years. The novel has a long history of being declared dead; the most famous modern manifesto on this seemingly ageless topic is American novelist John Barth’s “The Literature of Exhaustion” (1967). The death he announced, needless to say, hasn’t prevented Barth from publishing a whole string of novels in the wake of the novel’s wake. “If you were the author of this paper,” Barth playfully suggests, “you’d have written something like The Sot-Weed Factor or Giles Goat-Boy: novels which imitate the form of the novel, by an author who imitates the role of Author.”3 In a recent piece in the New Yorker, Louis Menand organized a review essay of three books on popular cinema around the “death of cinema” metaphor:

The cinema, like the novel, is always dying. The movies were killed by sequels; they were killed by conglomerates; they were killed by special effects. Heaven’s Gate was the end; Star Wars was the end; Jaws did it. It was the ratings system, profit participation, television, the blacklist, the collapse of the studio system, the Production Code. The movies should never have gone to color; they should never have gone to sound. The movies have been declared dead so many times that it is almost surprising that they were born, and, as every history of the cinema makes a point of noting, the first announcement of their demise practically coincided with the announcement of their birth.4

The things we love, it seems, are always dying; Gerald Marzorati even wrote a much-discussed article in the New York Times Magazine in 1998, arguing that the rock & roll album as a conceptual space was dead, “played out”: “Culturally speaking, the ambitious rock album is where it was in the early 1960’s of Top 40, the ‘Peppermint Twist’ and the Singing Nun: Nowhere.”5

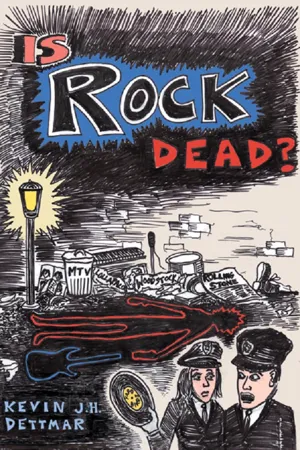

The titles of a handful of books for popular audiences may suggest the ongoing rhetorical power of the “death” trope; on my own music bookshelf alone, apart from my rock & roll titles, I see Henry Pleasants’s Death of a Music? The Decline of European Tradition and the Rise of Jazz; Donald Clarke’s The Rise and Fall of Popular Music; Nelson George’s The Death of Rhythm & Blues; and Mike Read’s Major to Minor: The Rise and Fall of the Songwriter. But if the death (or the ever-popular formula, derived from Edward Gibbon’s famous history of the Roman Empire, “rise and fall”) of various forms of popular music swirls like a rumor across the criticism, it seems almost an established fact within rock & roll writing. Books on the death of rock & roll nearly balance out those tracing its birth; again, on my own shelves, I find Steven Hamelman’s But Is It Garbage? On Rock and Trash; Bruce Pollock’s When the Music Mattered: Rock in the 1960s; Martha Bayles’s Hole in Our Soul: The Loss of Beauty and Meaning in American Popular Music; Joe S. Harrington’s Sonic Cool: The Life and Death of Rock ‘n’ Roll; Fred Goodman’s The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-On Collision of Rock and Commerce; James Miller’s Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977; Jeff Pike’s The Death of Rock ‘n’ Roll: Untimely Demises, Morbid Preoccupations, and Premature Forecasts of Doom in Pop Music; and John Strausbaugh’s Rock ‘Til You Drop: The Decline from Rebellion to Nostalgia. And again, this list doesn’t exhaust the books about the death of rock & roll: they are merely those that feature the trope (or a related one) in the book’s title, right there on the cover. (The most significant of these, as well as other writings exploiting the death trope, are the focus of chapters 3 and 4.) At the very least, we might begin to suspect that arguments for the death of rock & roll help to sell books.

A quick case study in the “death” of jazz—based largely on Gary Giddins’s suggestive essay, “How Come Jazz Isn’t Dead?”—may help to illustrate how very similar this rhetoric sounds across different musical genres. There’s enough resemblance, in fact, to suggest a nearly identical MO in the deaths of jazz and rock & roll—and enough to make us suspect foul play. “Jazz coroners have been hanging crepe since the 1930s,” Giddins points out; “Armstrong, they alleged, sounded the first death rattle when, in 1929, he adapted white pop from Tin Pan Alley.” But “at the dawn of its second century,” he suggests, jazz “affirms a template for the way music is born, embraced, perfected, and stretched to the limits of popular acceptance before being taken up by the professors and other establishmentarians who reviled it when it was brimming with a dangerous creativity.” Rock & roll, at the dawn of its second half-century, has already traced a very similar trajectory with fans and critics:

For half a century, each generation mourned anew the passing of jazz because each idealized the particular jazz of its youth. Countless fans loved jazz precisely because of the chronic, tricky, expeditious jolts in its development, but the emotional investments of the majority audience—which pays the bills—quickly metamorphosed from adoring into nostalgia.6

Although Giddins does not mention him in the essay, no better (or more articulate) example of this tendency can be found than the British poet Philip Larkin, who between 1961 and 1971 reviewed new jazz releases for the Daily Telegraph; his dismissive attitude toward nearly all post–World War II jazz is handily summed up in the title of one collection of his music writing, All What Jazz.7 More to our purposes here, Giddins realizes that the word jazz in the preceding quotation, and indeed throughout most of his essay, could easily be replaced with the phrase rock & roll, without the argument losing any of its validity.

According to the helpful model that Giddins develops, jazz has gone through four distinct “stations” in its first century; more than simply describing the stages of jazz history, however, Giddins sees himself as describing a structure that is nearly universal in the life cycle of popular music genres. Narratives of the life and death, or the equally popular “rise and fall,” of musical genres are thus to some degree what literary critics call “overdetermined”: the narrative has a logic and a momentum, we might even say a “mind,” of its own, and inconvenient facts are often trampled in its path; conclusions are quite predictable from the outset. As structuralist thinkers as far back as Claude Lévi-Strauss have emphasized, these large cultural narratives often tell us more about the societies that deploy and perpetuate them than they do about their ostensible objects of analysis. That the “rise and fall” of rock & roll so closely mirrors the “rise and fall” of jazz might conceivably tell us something about the great degree of similarity among the life cycles of all forms of popular music; but it might also tell us something about the compulsion to discover this pattern, about our need as a culture to kill off new musics “brimming,” as Giddins has it, “with a dangerous creativity.” When used to describe a form of high or popular art, “death” is of course always a metaphor and as such is hardly available to confirmation or rebuttal.

The first station in the life cycle of jazz and other popular musics Giddins dubs the “native”: “Every musical idiom begins in and reflects the life of a specific community where music is made for pleasure and to strengthen social bonds.”8 In rock & roll narratives, this community is usually the African American community, and its idiom the blues—although rock & roll is always acknowledged to be a mongrel of quite various pedigree. Hence the fetishization, in rock writing, of the concept of “authenticity”: rock & roll matters, justifies its existence (according to this model), to the degree that it can establish its solid connections to an organic community. So Bruce Springsteen, to pick a popular example, makes music that matters because his songs grow out of, and continue to speak to, the real concerns of real working Americans.9

Succeeding this first stage, according to Giddins, is the “second and most important,” the “sovereign,” which in jazz had taken over by 1940; “here,” Giddins writes, “music ceases to be the private reserve of any one place or people.”10 For rock & roll, as for jazz, this is the most significant, but also the most dangerous, of stages: for here, having at first wielded a myth of authenticity to argue for its primacy, rock & roll is challenged to tell the more complicated truth about its genealogy, to admit that mongrel pedigree. Rock & roll has no pure source but, having won a degree of legitimacy, it can now begin to come clean on the subject of its illegitimate birth.

However, as much as rock & roll embraces its ampersand, and celebrates the multicultural, interracial, generically hybrid condition of its existence, there have always been, and continue to be, audience members more distressed than pleased by this eclecticism. “When jazz became capacious enough to include Dixieland, boogie-woogie, swing, and modern jazz (or bop), the word jazz grew too large for the comfort of most listeners,” Giddins writes.11 Likewise, in the case of rock & roll, the tangled family tree from which rock arises, as well as the varied offspring to which it has given birth (sometimes bearing little or no family resemblance), push the imagined community “united” by rock & roll to the breaking point. The allmusic.com website, for instance, lists 175 “musical styles” under the heading “rock”; there is of course a good deal of overlap and hairsplitting involved here (one would be hard pressed, for instance, to explain the difference between “shoegaze” and “emo”), but the list, manic and obsessive though it may be, suggests something important about the variety that rock & roll comprehends. As the website says by way of prologue, “For most of its life, rock has been fragmented, spinning off new styles and variations every few years, from Brill Building Pop and heavy metal to dance-pop and grunge. And that’s only natural for a genre that began its life as a fusion of styles.”12 Interestingly, given questions we take up in chapter 6, this mother of all rock lists doesn’t include rap as a rock & roll style (listed separately, rap is further broken down into twenty-seven musical styles).

When the list gets too long—when jazz, or rock & roll, comprehends such a diversity that the centrifugal forces threaten to overpower the centripetal, and “the center cannot hold”—we arrive at the music’s third station. This is when rock & roll—or jazz, or alt-country, or disco, or shoegaze—is most in danger of being declared dead. Again, Giddins illuminates the situation with regard to jazz:

The widening gap between jazz and the public’s understanding of it … [suggests that] jazz was now sweeping inexorably toward the third station, which might be called “recessionary.” This occurs when a style of music is forced from center stage…. Yet it’s a mistake to think that the distancing of jazz from the commercial center resulted in a great decline in popularity. “Recessionary” means a retreat from marketplace power but not bankruptcy.13

Depending, again, on whether one considers rap a style of rock & roll, rock may have reached this recessionary station in 1991, when rap for the first time outsold more traditional rock & roll: the same year that saw the runaway success of Nirvana’s Nevermind also saw the first gangsta rap album reach number one in the Billboard charts, NWA’s Niggaz4life. Both signified, to some, the death of rock & roll.

Jazz has arrived at Giddins’s fourth station, and it seems just possible that rock & roll has, too. “The situation in which jazz is presently found,” Giddins writes of “the fourth and final station,”

might be called “classical,” not to denote an obeisance to orthodoxies and traditions (though, yes, there’s plenty of that), but because even the most adventurous young musicians are weighed down by the massive accomplishments of the past…. For the first time, a large percentage of the renewable jazz audience finds history more compelling than the present…. In a sense, the “classical” station is defined by the question: Who will inherit the music—the classicists or the renegades?14

The ubiquity of the term classic rock—an oxymoron that has become so naturalized that its oddness no longer even bothers us—perhaps suggests that rock & roll too has reached this station; fending off the challenge posed first by disco and later by rap, “classic rock” radio stations, proudly playing only “rock that really rocks,” represent the canonizing impulse within the rock & roll audience, who want rock & ro...