![]()

Chapter 1

Making mathematical errors

There are many reasons why people make mathematical errors. Sometimes mistakes are made through the slip of a pen or a moment of inattention never to be made again. Other times errors occur as a result of a slight misunderstanding or a lack of knowledge which is shortly to be attained and other times mistakes are the result of more fundamental misconceptions which are often difficult to unearth and which can take years to rectify. Some of these errors can be predicted; others cannot. Some are useful (see below); others are not.

Before I launch into my thoughts on the reasons for making errors I think it is important to stop and think:

| firstly of our successes—most of the time most of our pupils get most of their mathematics correct; |

| secondly we need to remember that mathematical errors are not inherently ‘bad’. On the contrary, as a mathematics teacher I would begin to worry if all of my pupils were getting everything right first time all of the time for it would suggest that I was not challenging them sufficiently. Of course it could mean that I was a brilliant teacher but even I would dispute that brilliant teachers should push their pupils to their limits and how do we know we have reached a child’s limits unless errors are beginning to creep in? |

| thirdly mathematical errors can prove an invaluable means of gaining insight into our pupils’ mathematical thinking; |

| and, finally, of course not all mathematics is about right and wrong answers… |

In this chapter we will explore some of the most common reasons for children making mathematical errors in school. The discussion will not be exhaustive but is intended more as an introduction to give an overview of the most likely roots of an error. For many, much of this chapter may be familiar but, hopefully, it will encourage you to reflect more on the particular source(s) of an error(s) than you might have done in the past.

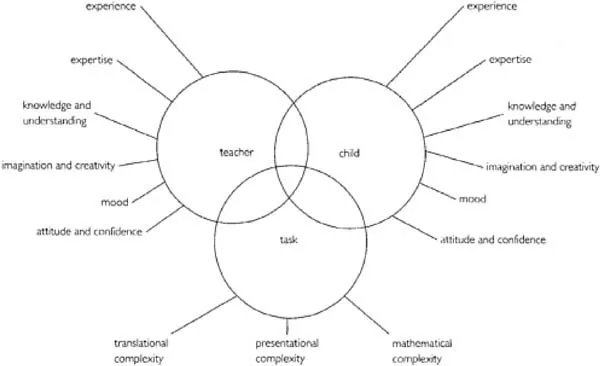

Figure 1.1 summarises some of the commonest sources of mathematical errors. Each will be discussed in turn but it is important to recognise that the causes are not necessarily mutually exclusive nor, indeed, that one can necessarily predict—or, at a later date, unravel—precisely how the various factors interact.

Child: Experience

Without wishing to state the obvious: it would be a little strange to assume that young children in a deprived area of London had a detailed knowledge of everyday life in provincial France (unless, I suspect, it was in a popular television soap!) And yet, taking a less striking example, it is surprising how many of us make assumptions about children’s experience of handling money and shopping. In the past, the vast majority of primary pupils gained experience of shopping by popping into the local corner shop and spending their pocket money. Nowadays this is far less common due to children’s more restricted lives on safety grounds, and due to the introduction of the plastic card. It is no longer wise to assume, therefore, that 6- and 7-year-olds are experienced money users: indeed, in the future, notes and coins may be a thing of the past.

FIG 1.1 Some of the commonest sources of mathematical errors

More generally mathematical errors and misconceptions may occur when teachers make unwarranted assumptions about their pupils’ experience. In the case of money, lack of experience may be one of the reasons that young children who have been used to counting cubes, consider all coins —regardless of denomination—as equal in value.

Child: Expertise

Although some may not like the concept, on entering school children have to learn to ‘play the game’. I have written about this in some detail elsewhere (Cockburn, 1995) but, to take an example from Dickson, Brown and Gibson (1984, p. 331), Percy was shown a picture of twelve children with the following problem written beneath them:

‘I have 24 lollies and I want each child to have the same number of lollies. How many lollies will I give each child?’ Percy’s response was,

‘I would give each child one lolly and keep 12 for myself.’

Percy it seems, was 12-years-old but, despite his age, I would suggest that either he did not possess, or chose not to use, experience in ‘playing the game’.

Child: Mathematical knowledge and understanding

When a child makes a mathematical error the most obvious possibilities to consider are,

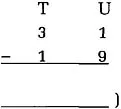

1 Does he or she know which procedure to apply? (e.g. does the child know that ‘+’ means ‘add’ rather than ‘subtract’ or ‘divide’?)

2 Does he or she know how to use the procedure correctly? (e.g. can the child do the necessary exchanging in the following sum requiring decomposition?

3 Does he/she understand the task both in terms of the language used and the mathematical implications?

Aspects of the above will be considered in more detail when I consider the translational complexity of tasks but here I wish to focus on language in particular.

Baroody (1993) considered, ‘For children, mathematics is essentially a second or foreign language’ (p. 2–99) sometimes, as teachers, we remember this but, I suspect, at other times we forget. For example words such as ‘plus’ and ‘subtract’ are obviously mathematical language but what about ‘check’ (more often a checked shirt than retry?), ‘face’ (what have people’s faces got to do with plain, old squares ?) or ‘take away’ (a delicious meal?). Clemson and Clemson (1994) provide a useful list of 22 everyday words with specific, technical meanings when used in early years mathematics and, I suspect, you would not find it hard to come up with a few of your own. Dickson et al. (1984) advise,

The acquisition of language and concepts is a dynamic process. It is not an all-or-nothing passive type of learning. The child’s understanding and use of language varies with the involvement of the child in the situation in which it is used, and with the relevance it holds for him. Since language development is dynamic in nature it is essential that the child and teacher should discuss various meanings and interpretations of words and phrases so each becomes aware of what the other means and understands by particular linguistic forms. The teacher is then in a position to help the child express himself more coherently. (p. 333)

Child: Imagination and creativity

When you stop to think about it, it is almost contradictory that in the early years classroom we may strive for a really creative and imaginative piece of work in one session, such as English, only to expect conformity and a decidedly unimaginative approach in the next. It may be a little hard to describe modern mathematics in such harsh terms as many teachers do encourage pupils to devise their own strategies to solve problems. Nonetheless, whether we like it or not, although mathematical processes are to be valued, mathematical products are often what it is all about: finding the right answer, by whatever means, is considered important. As busy teachers we may not always be tuned in to thinking about how a pupil’s imagination or creativity might have contributed to a wrong answer mathematically but a perfectly logical response in everyday terms.

Take the following. Desforges (1993) cites Jack Easley’s (1983) example of Japanese children who were asked to describe how many apples would be left if they started with a bowl of three and took two out. The children were also asked to justify their decision. The first two children responded correctly in mathematical terms but the third said that the matter could not be considered: his mother had told him that he must never take two apples at once! All three children had been using their imagination but only the third had taken it beyond the realms of the classroom and into the real world.

Most children quickly realise that finding the right answer is a major goal in mathematics sessions. Some do not find it easy as 12-year-old Benny illustrates, opposite.

E. | It [finding answers] seems to be like a game. |

B. | (Emotionally) Yes! It’s like a wild goose chase. |

E. | So you’re chasing answers the teacher wants! |

B. | Ya, ya. |

E. | Which answers would you like to put down? |

B. | (Shouting) Any! As long as I knew it could be the right answer. |

(Erlwanger, 1975, p. 10)

Such frustration can result in children creating a logic based on earlier successes which can be used to explain their subsequent errors. For example, Erlwanger’s Benny could add fractions—such as —and multiply decimals (.7×.5=.35) but he made errors when, in effect, he confused the two. Thus, on being asked to add ‘. 3’ to ‘.4’ he came up with ‘.07’ explaining ‘…there’s two points: at the front of the 4 and the front of the 3. So you have two numbers after the decimal.’ (Erlwanger, 1975, p. 6).

Child: Mood

As with everyone, mood can influence a child’s performance. An individual’s motivation to focus on the task at hand can easily be affected by whether his or her team won the previous night or whether he or she has just had an argument with a best friend. If you are not in the mood your performance may well not be a true reflection on your ability.

Similarly, carelessness—say if you are in a frantic rush to move on to the next activity—can lead to mistakes which might not otherwise have occurred had you been concentrating. Tiredness can also result in carelessness as I have discovered to my cost on occasion after an over-indulgent lunch!

Child: Attitude and confidence

Children’s attitudes to both their teachers and mathematics should not be underestimated when it comes to judging their ability. If a child has the potential to be a brilliant mathematician, ...