- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Just what is a picture worth? Qualitative research is dominated by language. However, researchers have recently shown a growing interest in adopting an image-based approach. This is the first volume dedicated to exploring this approach and will prove an invaluable sourcebook for researchers in the field. The book covers a broad scope, including theory and the research process; and provides practical examples of how image-based research is applied in the field. It discusses use of images in child abuse investigation; exploring children's drawings in health education; cartoons; the media and teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Image-based Research by Jon Prosser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralPart 1

A Theoretical Overview of Image-Based Research

Editor’s Note

The chapters in this section cover mostly historical, epistemological, theoretical and methodological overviews. They represent a cross-section of disciplines including anthropology, psychology and sociology and consequently a cross-section of perspectives on Image-based Research. However, they display a number of similarities in that each demonstrates an awareness of the limitations of visual research as well as its strengths. They also offer a framework for understanding how particular forms of Image-based Research are located in their respective disciplines.

Chapter 1

Visual Anthropology: Image, Object and Interpretation1

Abstract

Until recently, the subdiscipline known as visual anthropology was largely identified with ethnographic film production. In recent years, however, visual anthropology has come to be seen as the study of visual forms and visual systems in their cultural context. While the subject matter encompasses a wide range of visual forms—film, photography, ‘tribal’ or ‘primitive’ art, television and cinema, computer media—all are united by their material presence in the physical world. This chapter outlines a variety of issues in the study of visual forms and argues for rigorous anthropological approaches in their analysis.

Anthropology and Visual Systems

In recent years there has been an apparent shift in anthropology away from the study of abstract systems (kinship, economic systems and so forth) and towards a consideration of human experience. This has resulted in a focus on the body, the emotions, and the senses. Human beings live in sensory worlds as well as cognitive ones, and while constrained and bounded by the systems that anthropology previously made its focus, we not only think our way through these systems, we experience them. For anthropology, this has involved a shift away from formalist analytical positions—functionalism, structuralism and so forth— towards more phenomenological perspectives. Correspondingly, under the much misapplied banner of postmodernism, there has been an increased focus on ethnography and representation, on the modes by which the lives of others are represented. At worst, this has been manifest in a depoliticization of anthropology, an extreme cultural relativism that concentrates on minutiae or revels in exoticism, and a deintellectualization of anthropology where all representations are considered equally valid, where analysis is subordinate to (writing) style, and where injustice, inequality and suffering are overlooked. At best, the new ethnographic approaches are historically grounded and politically aware, recognizing the frequent colonial or neo-colonial underpinnings of the relationship between anthropologist and anthropological subject, recognizing the agency of the anthropological subject and their right as well as their ability to enter into a discourse about the construction of their lives (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Gabriel Reko Notan Discusses His Experience as a Telegrapher for the Dutch East India Government with Anthropologist R.H. Barnes, in Witihama, Adonara, Indonesia

Until recently, visual anthropology was understood by many anthropologists to have a near-exclusive concern with the production and use of ethnographic film. In the first half of the century it was film’s recording and documentary qualities that were chiefly (but not exclusively) valued by anthropologists. But while film could document concrete and small-scale areas of human activity that could subsequently be incorporated into formalist modes of analysis by anthropologists—the production and use of material culture, for example—it quickly became apparent that it could add little to our understanding of more abstract formal systems—in kinship analysis, for example. From the mid- to late-1960s onwards attention turned instead towards the pseudo-experiential representational quality of film, anticipating the appreciation of a phenomenological emphasis in written ethnography by a decade or two. Now film was to be valued for giving some insight into the experience of being a participant in another culture, permitting largely Euro-American audiences to see life through the eyes of non-European others.

While in some ways very different positions—film as science, film as experience —there is an underlying commonality between them. Both positions hold film to be a tool, something that allows ‘us’ to understand more about ‘them’. More specifically, film was something ‘we’ did to ‘them’. We can hypothesize that this is one of the reasons why ethnographic film came to dominate what became known as visual anthropology.2 Ethnographic film produced using 16mm film cameras renders the anthropologist/filmmaker entirely active, the film subject almost entirely passive. Beyond altering their behaviour in front of the camera (or indeed, refusing to ‘behave’ at all) the film subjects have little or no control over the process. Partly for technical reasons they rarely if ever get to see the product before it is complete and they typically have no access to 16mm equipment to effect their own representations. Ethnographic still photography, probably more commonly produced than ethnographic film for much of the century, has been very much a poor second cousin to film in the traditional understanding of visual anthropology, perhaps because the active-passive relationship between anthropologist and subject is less secure: ‘the natives’ can have and have had more access to the means of production and consumption.

What was missed until recently was that film was one representational strategy among many. A particular division lies between written and filmed ethnography (see Crawford and Turton, 1992), but within the realm of the visual alone there are clearly differences between forms. For example, ethnographic monographs are frequently illustrated with photographs, very often illustrated with diagrams, plans, maps and tables, far less frequently illustrated with sketches and line drawings. Yet even this range of representations— some full members of what is traditionally understood to be the category of visual anthropology, some far less so— consists largely of visual forms produced by the anthropologist. Traditionally, the study of visual forms produced by the anthropological subject had been conducted under the label of the anthropology of art. Only very recently have anthropologists begun to appreciate that indigenous art, Euro-American film and photography, local TV broadcast output and so forth are all ‘visual systems’—culturally embedded technologies and visual representational strategies that are amenable to anthropological analysis.3 Visual anthropology is coming to be understood as the study of visible cultural forms, regardless of who produced them or why. In one sense this throws open the floodgates —visual anthropologists are those who create film, photography, maps, drawings, diagrams, and those who study film, photography, cinema, television, the plastic arts—and could threaten to swamp the (sub) discipline.

But there are constraints; firstly, the study of visible cultural forms is only visual anthropology if it is informed by the concerns and understandings of anthropology more generally. If anthropology, defined very crudely, is an exercise in cross-cultural translation and interpretation that seeks to understand other cultural thought and action in its own terms before going on to render these in terms accessible to a (largely) Euro-American audience, if anthropology seeks to mediate the gap between the ‘big picture’ (global capitalism, say) and local forms (small-town market trading, say), if anthropology takes long-term participant observation and local language proficiency as axiomatic prerequisites for ethnographic investigation, then visual studies must engage with this if they wish to be taken seriously as visual anthropology.4 Not all image use in anthropology can or should be considered as visual anthropology simply because visual images are involved. It is perfectly possible for an anthropologist to take a set of photographs in the field, and to use some of these to illustrate her subsequent written monograph, without claiming to be a visual anthropologist. The photographs are ‘merely’ illustrations, showing the readers what her friends and neighbours looked like, or how they decorated their fishing canoes. The photographs are not subject to any particular analysis in the written text, nor does the author claim to have gained any particular insights as a result of taking or viewing the images. It is also possible for another anthropologist to come along later and subject the same images to analysis, either in relation to the first author’s work or in relation to some other project, and to claim quite legitimately that the exercise constitutes a visual anthropological project.5

A second constraint returns us to a point I made in the opening paragraph. One of the reasons for the decline of formal or systems analysis in anthropology—particularly any kind of analysis that took a natural sciences model6—was the realization that formal analytical categories devised by the anthropologist (the economy, the kinship system) were not always that easy to observe in the field, being largely abstract. To be sure, earlier generations of anthropologists were confident both of the existence of abstract, systematized knowledge in the heads of their informants, and of their ability to extract that knowledge and present it systematically, even if the informants were unconscious of the systematic structuring. However, as these essentially Durkheimian approaches lost ground in the discipline, and as anthropologists concentrated more on what people actually did and actually thought about what they were doing, so doubts began to set in about how far any systematicity in abstract bodies of knowledge was the product of the anthropologists’ own rationality and desire for order.7 This does not, however, invalidate the current trend in anthropology towards seeing visual and visible forms as visual systems. The crucial difference between the visual system (s) that underlie Australian Aboriginal dot paintings and a particular Aboriginal kinship system is that the former is/are concrete, made manifest, where the other is not and cannot be except in a second-order account by an anthropologist. It is the materiality of the visual that allows us to group together a diverse range of human activities and representational strategies under the banner of visual anthropology and to treat them as visual systems. With some important exceptions, the things that visual anthropologists study have a concrete, temporally and spatially limited existence and hence a specificity that a ‘kinship system’ or an ‘economic system’ does not and cannot.8

In what follows, I shall unpack some of the ideas above, relating them more specifically to the history of visual anthropology, and some specific examples.

The Visual in Anthropology

The history of the visual in anthropology cannot be properly told or understood outside of an account of the history of anthropology itself, for it is intimately related to changes in what is understood to be the proper subject matter of anthropology, what methodology should be used to investigate that subject matter, and what theories and analyses should be brought to bear on the findings. Clearly this is not the place to rehearse the entire history of the discipline and the reader with less familiarity with anthropology’s origins and subsequent development should turn to another account.9 There have been one or two pieces by anthropologists, however, that have explicitly linked the parallel histories of anthropology and either photography (for example, Pinney, 1992c) or cinema (for example, Grimshaw, 1997).

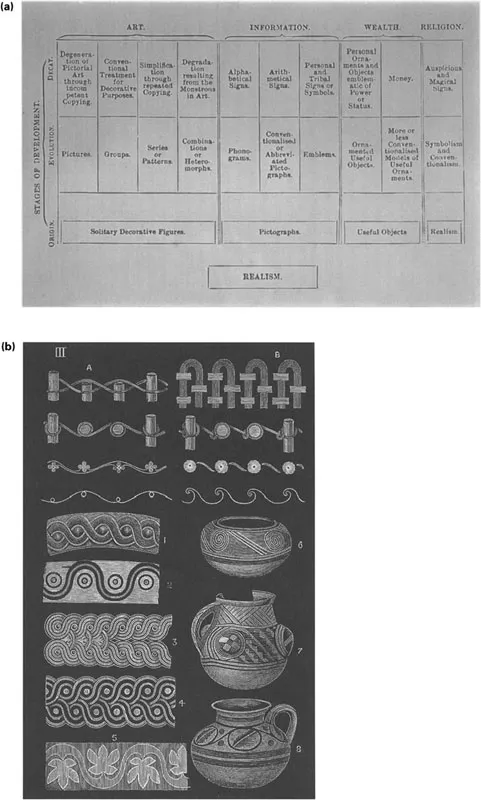

Nonetheless, for much of anthropology’s history the emphasis was on the study of indigenous visual systems (usually under the label of ‘primitive art’) and comments on the uses of film and photography by anthropologists were confined to methodological footnotes and the like until the last two decades or so. By and large, studies in the anthropology of art have mirrored wider theoretical concerns in the discipline as a whole, although, as Coote and Shelton note, the subdiscipline has ‘hardly—if ever—taken the [theoretical] lead…[and] it is yet to significantly influence the mainstream’ (1992, p. 3). Typically, from the early days of anthropology, we find works such as Haddon’s Evolution in Art (1895) which attempts to trace the ‘evolution’ of stylistic devices by applying then-standard but now discredited social evolutionary theory developed in the second half of the nineteenth century (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 (a) Synoptic Table of Stylistic Evolution and Decay from Haddon’s Evolution in Art (1895:8); (b) ‘Skeuomorphs of Basketry’ (Haddon 1895, Plate III) Showing Hypothetical Origins of Scroll Designs (Top) and Examples of Bronzework and Pottery Designs Supposedly Derived from These

Yet despite the influence of ‘Primitivism’ on artists such as Picasso and the Cubists earlier generations of anthropologists resolutely confined themselves to the study of ‘primitive art’ in its own cultural setting and failed to set an agenda that would concern itself with ‘art’ as a broad category. This has not only led to an absence of anthropological studies of European ‘fine art’ and artists (and those elsewhere working within a European-influenced tradition) until recently, it has also led to an absence of anthropological studies of art in societies where anthropologists have long worked (such as China, Japan and India) but where the high culture of those societies, including their art forms, has been the preserve of other scholars.10 Yet while these earlier studies insulated themselves from the traditions of art history and connoisseurship, they were nonetheless influenced (if unconsciously) by Euro-American categories of ‘art’ and the art object. It is only recently that the issue of aesthetics has been examined by anthropologists of art. Alfred Gell has urged the adoption of ‘...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I A Theoretical Overview of Image-Based Research

- Chapter 1 Visual Anthropology: Image, Object and Interpretation

- Chapter 2 An Argument for Visual Sociology

- Chapter 3 Film-Making and Ethnographic Research

- Chapter 4 ‘The Camera never Lies': The Partiality of Photographic Evidence

- Chapter 5 Psychology and Photographic Theory

- Chapter 6 Visual Sociology, Documentary Photography, and Photojournalism: It's (Almost) All a Matter of Context

- Chapter 7 The Status of Image-Based Research

- Part II Images in the Research Process

- Chapter 8 Photographs within the Sociological Research Process

- Chapter 9 Remarks on Visual Competence as an Integral Part of Ethnographic Fieldwork Practice: The Visual Availability of Culture

- Chapter 10 Photocontext

- Chapter 11 Media Convergence and Social Research: The Hathaway Project

- Chapter 12 The Application of Images in Child Abuse Investigations

- Part III Image-Based Research in Practice

- Chapter 13 Picture This! Class Line-Ups, Vernacular Portraits and Lasting Impressions of School

- Chapter 14 Interpreting Family Photography as Pictorial Communication

- Chapter 15 Pupils Using Photographs in School Self-Evaluation

- Chapter 16 Cartoons and Teachers: Mediated Visual Images as Data

- Chapter 17 Images and Curriculum Development in Health Education

- Chapter 18 Making Meanings in Art Worlds: A Sociological Account of the Career of John Constable and His Oeuvre, with Special Reference to ‘The Cornfield' (Homage to Howard Becker)

- Notes on Contributors

- Index