![]()

Chapter I

Evidence in psychotherapy

A delicate balance

Chris Mace and Stirling Moorey

‘Evidence in the Balance’ was the title of a conference organised by the Psychotherapy Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the University Psychotherapy Association and the Association of University Teachers of Psychiatry. The discussions that took place of why and how psychotherapeutic services might be more ‘evidence based’ deserve a wider audience. Since the meeting, ways in which ‘evidence’ is likely to impinge on everyday practice have been clarified within the National Health Service’s programme of ‘clinical governance’. This strategy, and the wholesale reform of the service’s institutions that it entails, has been a cornerstone of the drive to include quality assurance within the responsibilities of NHS providers (cf. Mace, 1999). Evidence-based practice is no longer a movement that any clinician can ignore.

The psychotherapies, given their respect for the uniqueness of the individual, the complexity of the questions with which they deal, and attitudes towards scientific method that range from willing borrowing to deep distrust, pose particular problems for this movement. The contents of this book should ensure that a psychotherapist, whatever his or her interests, is not only better informed about the clinical implications of evidence-based practice, but better able to recognise its strengths and weaknesses, and able to meet its requirements at the level of service organisation.

Science and psychotherapy

The relationship of systematic research to clinical practice has varied according to individual interests and the history of different psychotherapeutic schools. Cognitive-behavioural psychotherapies, with their past association with learning theories derived from animal experiment and laboratory studies of human cognition, have been seen as intrinsically more ‘scientific’ than psychoanalytic practices developed through engagement with patients in planned therapeutic environments. Hans Eysenck (1990) used to claim that a psychologist with no clinical experience, but properly versed in experimental method, required about six weeks to translate this scientific understanding into clinical practice. Despite the claims of both Freud and Jung to offer a scientific understanding of the unconscious mind, psychoanalysis has been regularly singled out by philosophers of science as a prime example of a ‘pseudoscience’ (e.g., Popper, 1962). These stereotypes may require some adjustment. While cognitive-behavioural approaches in clinical practice are increasingly based upon clinically rather than experimentally derived models, psychodynamic practice has been enriched by much closer reference to findings in developmental psychology (cf. Chapter 3 in this book).

In recent years, the efficacy rather than the validity of psychotherapy has been subjected to increasingly sophisticated scrutiny. Research into psychotherapy outcomes had been taken to support the view that psychotherapy was effective, but that there was little overall difference between different forms of psychotherapy. Following a suggestion of Lester Luborsky (Luborsky et al., 1975) this is often called the ‘Dodo bird verdict’ after Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In Carroll’s story, the Dodo proposes that a ‘Caucus-race’ is held and, after half an hour or so of running, announces that the race is over and ‘Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.’ One might question the rigour of the Dodo’s methodology—the race course is a ‘sort of circle’, the participants all start at different points along the course, and they can begin running when they like and leave off when they like: a set of rules that seemed to have been used in some of the early psychotherapy trials! There is an increasing sophistication in outcome research, with attempts to specify the goals of treatment more clearly, to define the treatment delivered and to ask questions such as ‘what therapy works for which condition’ (cf. Roth and Fonagy, 1996). Techniques such as meta-analysis for aggregating research findings, which had supported the Dodo bird verdict, have been refined with more discriminating results. Some researchers are now reasserting that among the psychotherapies (in the words of another modern fable) ‘some are more equal than others’.

Principles of evidence-based practice

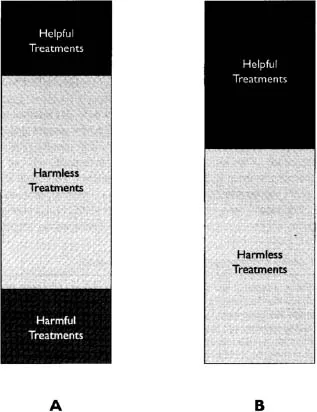

While some psychotherapy practitioners have always been motivated to translate clinical questions into ones that can be answered through systematic research, the directional shift that turns research into an activity that should normally guide practice is new and decisive. It has been justified by the existence of findings in many clinical fields that appear sufficiently robust to provide a rational basis for selection between treatments in the care of individual patients. The underlying philosophy of evidence-based care can be summed up diagrammatically as a transition between two states of affairs (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The aims of evidence-based practice.

In the first situation (column ‘A’) ignorance about the relative efficacy of treatments prevails; the majority of available interventions are taken to be harmless, with small but significant minorities being either distinctly beneficial or clearly harmful. The task of evidence-based practice is to increase the use of the former and to eliminate the latter, this being the desired state of affairs represented by column ‘B’. (Chapter 4 offers an exemplary discussion of the importance of both of these.) To do this, there not only need to be recognised standards of what kind of research findings will count as clinical evidence, but a mechanism for translating these into clear, widely disseminated recommendations that fulfil the needs of any clinicians and patients asking specific questions about ‘best practice’. This is the role of clinical guidelines, statements that reflect the balance of research evidence and clinical consensus as to the action that is ordinarily appropriate to a given problem. This guidance will indicate the treatments that should be adopted and any that may be considered but which are no longer recommended, in accordance with the shift from ‘A’ to ‘B’ in Figure 1.1.

Table 1.1 Levels of evidence of therapeutic effectiveness Source: After Ball et al. (1998)

Level 1 Either a systematic review of comparable randomised controlled trials, or an individual RCT with a narrow confidence interval, or introduction of the treatment has been associated with survival in a previously fatal condition

Level 2 Either a systematic review of comparable cohort studies, or an individual cohort study (which may be a RCT with a significant drop-out rate)

Level 3 A systematic review of comparable case-control studies, or an individual case-control study

Level 4 A reported case series (or poor quality cohort or case-control studies)

Level 5 Expert opinion based on consensus or inference from ‘first principles’ in the absence of formal critical appraisal

Source: After Ball et al. (1998)

Decisions as to what counts as the most valid kind of evidence are unlikely to be universal across all kinds of clinical knowledge, nor to be immutable. However, it is fair to report that hierarchical judgements do prevail, and the grading given in Table 1.1, discriminating between the quality of evidence for an intervention’s therapeutic effectiveness, is fairly typical.

The highest grade of evidence is identified with the Randomised Control Trial (RCT). Here, the impact of a treatment is studied following attempts to eliminate bias by randomly allocating alternative treatments to study patients according to a protocol over which an experimenter has no personal control. Assessments are conducted by people ignorant of (‘blind’ to) the nature of the treatment given, and ideally patients too remain ignorant of the kind of treatment they have received—an almost impossible requirement in psychological treatments. This ideal standard of objectivity can be diluted in a number of ways—whether evaluation was in fact comparative, the quality of matching between comparison groups, the extent to which those entering the study are followed up. These are all reflected in the gradings described in Table 1.1. It does not and cannot take into consideration additional questions—vital to the validity of individual research reports as a means of addressing clinical decisions— such as how far treatments evaluated under experimental conditions resemble those provided in routine care, or how far outcome measures used by researchers are clinically meaningful.

At most levels, evidence can be in the form either of a report of validated research (e.g., a RCT), or a systematic review of several reports which fulfil clear criteria for their inclusion in the review. This has generated a need for information concerning individual research studies to be indexed and archived in formats which guarantee their accessibility to clinicians seeking evidence of the comparative merits of interventions they may provide. It has also meant that systematic reviews, collating all work meeting a given quality standard that allows a question to be answered, have assumed great significance. The trend for their compilation and dissemination to be sponsored is likely to grow. At the same time, recognition that the quality of systematic reviews is restricted by the availability (and completeness) of published reports of the work they examine is likely to fuel demands that the results of all funded research, whether these fulfilled a study’s original objectives or not, are made publicly available for incorporation in systematic reviews (cf. Sturdee in Chapter 5).

Beyond the dissemination of evidence in pre-digested forms in these ways, evidence-based practice has been seen to depend upon the translation of evidence in practice guidelines. These distil the practical implications of research into clear advice concerning what kinds of action constitute ‘best practice’ in a given situation with the present state of knowledge. In this way, clinical guidelines, in defining objective standards of practice, provide a clear reference point by which actual practice might be audited and, in principle, improved. Whereas guidelines have been produced in the past by professional bodies, the introduction of such new structures as National Service Frameworks, and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) within the National Health Service, provides a mechanism by which guidelines can not only be approved and disseminated but adopted as standard clinical practice throughout the public health system.

Evidence and psychotherapy

‘Evidence’ has several facets which are treated in turn through the remainder of this book. The first concerns the nature of evidence itself. In an effort to dig behind the assumption that we all know what counts as evidence, the distinguished lawyer John Jackson was invited to explain the nature of evidence in law (Chapter 2). It is apparent that the legal concept of evidence—grounded in the need to resolve a case— differs significantly from the scientific one on which the evidence-based practice movement bases its proposals. In law, testimony is valued only for its contribution to resolution of a dispute—irrespective of how far it may also provide a truthful description.

The contrast with the view that equates evidence with that which is scientifically validated will be apparent from Chapter 4. In it, Simon Wessely justifies the importance that has been placed upon the randomised controlled trials among the kinds of research evidence that are available. As several other contributors highlight the special difficulties of conducting controlled trials for psychotherapeutic treatments (cf. Chapters 11 and 12) their necessity needs to be fully and widely accepted. The case Wessely presents is powerful, depending not only on the relative quality of RCTs as a form of evidence for the efficacy of a treatment, but also on their unique capacity to demonstrate in the face of received wisdom when treatments are positively harmful.

Wessely’s polemical tone is reciprocated by Paul Sturdee’s in Chapter 5—a discussion of the dangers of allowing an evidence-centred approach to dominate clinical practice when the ‘evidence’ in question is only partial. Sturdee looks at the impact this attitude can have on the balance between physical and psychotherapeutic treatments for people with mental health problems—not only on how they are perceived, but on their potential availability. Indeed, Sturdee’s objections to the selective use of evidence in the name of objectivity suggest that the courtroom model may not be such an inaccurate image of clinical debate. To correct things, Sturdee makes several suggestions. One, the idea that an approach is not properly evidence-based until all relevant evidence is actively sought and then taken into account, is slowly being accepted. However, some fundamental conflicts between the values of science and the individual that he also indicates seem more intractable.

A different evaluation of the evidential thinking in psychotherapy is offered by Michael Rustin (Chapter 3). While Wessely and Sturdee concentrate on the outcome or efficacy of psychotherapy, Rustin illustrates how research can be used to substantiate the theories which therapists use to guide their practice. Given that much therapeutic practice is founded on theories of human development and the impact of early experience on adult functioning, external evidence that supports these accounts of development will consolidate knowledge shared within the psychotherapeutic community. Evidence of this kind also exposes limitations of the drug metaphor. Psychotherapy sets out to explain as well as to treat, and gains a different kind of authority when its explanations are seen to have validity independent of their usefulness in treatment. However, this should not be confused with evidence that its treatments are effective, any more than evidence of a treatment’s efficacy is a valid argument for the truth of its theoretical basis. (A definitive discussion of the difference between these arguments will be found in Grünbaum, 1984).

The heterogeneous nature of evidence in psychotherapy underpins Digby Tantam’s essay on the relationship between reasons and causes (Chapter 6). Much confusion is attributed to assumptions either that the reasons people give for their actions are unrelated to their causes, or that they constitute the only causes for what people do. In a philosophically skilful argument, Tantam distinguishes between the two kinds of causes that these represent, illustrating the kind of evidence that is necessary to identify either kind with confidence.

If these opening chapters demonstrate that evidence takes many forms within such a psychologically complex field, they set the scene for the remaining chapters of the book. These deal with how evidence accrues, in research and in practice, and how it can be used by psychotherapists to enhance their practice.

The discussion of standards of evidence showed that, within scientific medicine at least, relatively little value was placed on the contribution that individual case studies could make (cf. Table 1.1). This view is likely to be reinforced as critical reviews of the evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapy organise themselves around these standards when deciding whether a given therapy is ‘empirically supported’ (cf. Roth and Fonagy, 1996). Although the formative history of the psychotherapies was dominated by individual case studies, the tendency to minimise their significance seems to be increasingly common. Graham Turpin illustrates the contribution that individual case studies can still make to the evidence base, providing a survey of the strengths and drawbacks of qualitative methods in doing so (Chapter 7).

Whether or not individua...