eBook - ePub

A Handbook of Techniques for Formative Evaluation

Mapping the Students' Learning Experience

- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Handbook of Techniques for Formative Evaluation

Mapping the Students' Learning Experience

About this book

This handbook provides all those teaching in higher and further education with a reference on how to develop and use a "toolkit" which is capable of exploring and assessing all the relevant aspects of their students' learning. It discusses how readers can assess their own teaching quality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Handbook of Techniques for Formative Evaluation by John Cowan,Judith George in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Approaching Curriculum Development Systematically

Where Does Formative Evaluation Fit in?

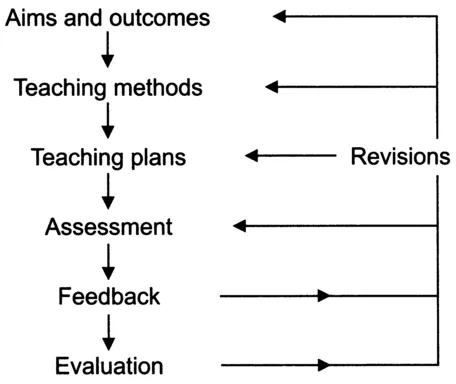

Most texts on curriculum development assume a linear model with a feedback loop (see Figure 1.1). Their linear process describes, in varying terms but with fairly constant features, the chronological sequence in which:

- aims and outcomes are determined;

- teaching methods and arrangements are chosen;

- teaching plans are prepared;

- teaching is delivered;

- students learn;

- teachers assess students;

- feedback is obtained from students (and perhaps others);

- the course is evaluated (usually by those who prepared and presented it);

- revisions are determined;

- the cycle begins again.

We have some difficulties with that sequence because:

- it assumes that aims and outcomes are only considered, and reviewed, once per cycle or iteration;

- it concentrates on teaching rather than learning;

- it presents learning as a consequence of teaching, rather than teaching as one, but not the only, input to learning;

- it obscures the relationships between the elements of process.

Figure 1.1 Traditional curriculum development

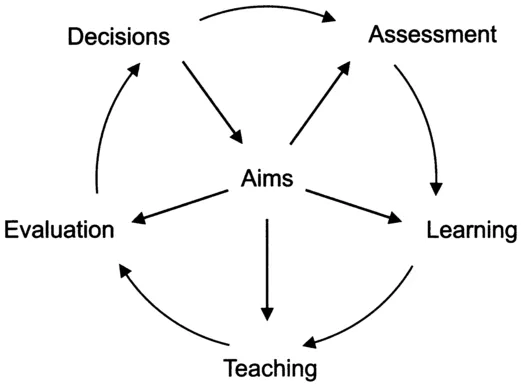

We, therefore, prefer to relate our thinking to the logical, rather than chronological, model advanced by Cowan and Harding.1 In this model, aims (which we are using as a portmanteau expression for 'aims, outcomes and/or objectives') are set at the centre (see Figure 1.2). The learning outcomes that we hope our learners will achieve are thus assumed, through the radial and mainly outward arrows, to influence and be influenced by all that occurs in the preparation and presentation of the curriculum.

Figure 1.2 A logical model for curriculum development

The first element on the perimeter is then assessment, which is known from research to be the most powerful influence on student learning, well ahead of the declared syllabus or the published learning outcomes.2 Hence this, logically, is the first circumferential arrow in Figure 1.2.

Learning will then be a response on the part of the student to the perceived messages from both the declared aims and outcomes, and the assessment - all of which, hopefully, will be giving the same messages.

Teaching, we believe, should then be designed to meet the needs of learners who are striving to meet the objectives inherent in the assessment, and critical to the aims. Learning styles, strategies and needs thus influence teaching, or should do so, through our next circumferential arrow.

We take evaluation, as we have explained, to be an objective process in which data about all that has gone before is collected, collated and analysed to produce information or judgements.

Subsequently decisions for action, including changes in aims, are made on the basis of the evaluation, and in terms of the course aims or goals. Such decisions will not usually be made by those who undertook the evaluation, and will preferably always involve the responsible teachers.

When the evaluation primarily leads, as we would hope it often does, from one iteration to the next, it is essentially formative. Hence it is formative evaluation which is the bridge between data collection and development. On the relatively rare occasions when purely summative evaluation is called for, a judgement of quality as an end product is desired, and there is no intention to move on to a further developmental iteration. Summative evaluation, therefore, is peripheral to the process of curriculum development.

Why is it an Iterative Process?

Iteration is at the heart of successful curriculum development; because, for each cycle to benefit from the experience of its predecessor, there must be a constructive link forward and into the next development. We need not apologize that this is so, for most good design - in any discipline - is iterative. When we teach something for the first time, even if it is only the first time for us, we prepare as thoughtfully as we can; but there will be some challenges that we underestimate, some factors that we do not anticipate, and some possibilities that we do not fully utilize. After our first presentation of this particular course or activity, we still expect to discover that improvement may be possible. And, if we care about our students and our teaching, we plan for such change - so that the second iteration will be an improvement on the first. We should, therefore, always be on the lookout for the information on which a well-grounded judgement for improvement will be based: for 'students are reluctant to condemn, and rate few teachers poorer than average'.3 And so we need to seek such information rigorously.

Sadly, there are many educational decisions even today which are made for reasons that are unsound. They may stem from a desire to teach in a certain way, from a memory of teaching that proved effective for the teacher many years ago, or from habit or educational folk wisdom, or even from ignorance. Such decisions are ill-founded, even if they happen to lead to improvement. They do not build systematically and purposefully on the experience of a previous iteration. That is why we criticize them as unsystematic, and argue for the need to build instead upon a well-informed and accurate perception of the experience of the previous iteration - in order to improve the next one. Such a process gives the teaching of a subject the same rigour and sound basis as its content. This plea applies both at the micro-level - to the shaping of the introductory tutorial which you always give for new students, for example, or even the approach you take to teaching a particular concept or formula; and also at the macro-level - in the design and implementation of an entirely new course or module.

Arranging for formative evaluation is the means by which you can build into your present plans the possibility of an eventual refinement of what you are doing at present. It entails building in the opportunity to find out, as you go along, how things are for your current learners. It should be the means by which you find out whether what you planned is matched by what is actually happening for your students. It is the source of the data on which you will base your judgements about improvements and fine-tuning to be made. It is also the means by which, on a regular basis and within a familiar context, you check on how well you are doing as a teacher; is your students' experience actually what you hoped and intended? The habit of evaluative enquiry, over time, will help you to build up a well-founded professional expertise, so that, because of the rigorous way in which you have tested out and checked what you do, you can be more accurately informed about what works and what doesn't. Hence you will be building up a repertoire of teaching approaches and techniques which, you can be confident, will work well for your students. Such a basis for practice moves good 'amateur' work, derived often from no more than the accumulated, but perhaps unverified, experience of enthusiastic but unsystematic teachers, into the realm of true professionalism.

In addition to the findings of your formative evaluations, there will be other items of information from the wider context of the student learning environment. These can helpfully inform your process of development, but are incidental to your direct contact with and support of students. It is worth being aware of them and considering their potential use, in order to build review of them into your processes, if relevant. This data perhaps calls for some time and trouble to dig it out and analyse it, and might cover:

- entry qualifications;

- patterns of take-up for options;

- pass, fail, transfer and drop-out rates;

- rates of progression towards merits and honours;

- patterns of distribution of marks;

- first degree destinations;

- attendance patterns, levels of attentiveness and readiness to commit;

- patterns of choice in essays, projects and exam questions;

- comparisons with other programmes and their evaluations.

We note here the value or such collections of data,4 especially since they are becoming increasingly easy to access and analyse, as institutional records are computerized. And we would put in a plea that, as institutional and information technology (IT) change is planned, it is important to consider making such data more easily available to teachers, as it is directly relevant to their understanding of their students.

What Approaches to Evaluation Are There?

Researchers have identified three main approaches to educational evaluation. Firstly, and commonly, it is possible to concentrate on producing quantitative records of such items as teachers' efficiency and effectiveness, and learners' progress. For example, testing learners before and after a lesson can be a means of measuring the learning that the test identifies as occurring, or not occurring, during the lesson. Drop-out rates and attendance records may say something about motivation, and students' perceptions of teachers. These behaviourist or quantitative approaches, which concentrate on behaviour that can be measured, and on outcomes that have or have not been achieved, feature useful information.5 But you should be aware that they do not cover interpersonal processes or any unintentional outcomes of the teaching and learning situation, which may or may not also prove valuable input to an evaluation.

An option is to attempt to identify all die effects of the course provision, and relate these to the rationally justifiable needs of the learners. Such an approach, usually termed 'goal-free', will obviously depend considerably on open-ended questionnaires, unstructured interviews, record keeping, and on the rationality and objectivity of teachers, learners and especially of evaluators.6 We suggest that this is more readily obtainable, and more feasibly resourced, in full (and summative) educational evaluation, than in the type of enquiry which you will have in mind, as a busy teacher.

Finally, there is a family of approaches variously termed 'illuminative' or 'transactional' or 'qualitative'.7 These attempt to identify a broad view of a range of expectations and processes, and of ways in which the programme is seen and judged, including its unexpected outcomes. This is the grouping to which we relate most of the approaches in this handbook, especially if you take our advice to combine several methods of enquiry to obtain a range of perspectives on your teaching and your students' learning. It will not concern you that the findings of such evaluations do not generalize well, for you only wish to focus on your own teaching and your students' learning. But you should be aware nonetheless that qualitative approaches run the risk, in unskilled hands, of subjectivity and relativism. And, in any case, you may wish to triangulate qualitative data of a significant nature with a larger sample of students to establish its quantitative validity.

We should declare here our own preference for a version of what is termed 'illuminative evaluation'. This follows a process of progressive focusing in which the evaluator on behalf of the teacher(s):

- does not set out with a predetermined purpose to verify or dispute a thesis;

- tries to observe without being influenced by preconceptions and assumptions;

- thus attempts to observe, consider and study all outcomes;

- nevertheless pays particular attention to any emerging features that appear to warrant such attention;

- reports objectively and descriptively, without judgement - implied or explicit.

Notice, however, that this approach demands a separate evaluator, and additional resources. We can on occasions transfer some of the open-endedness of illuminative evaluation into our own modest formative evaluations. However, on the whole, these must necessarily be focused by our immediate needs as teachers and as planners of development.

What Kind of Information Do You Need from Formative Evaluation?

We advise you to begin by working out the place of formative evaluation within the macro-level of what you do. That means thinking first of enquiries which will be made witnin the wide canvas of an enquiry about a particular course or module design, or a curriculum innovation. However, techniques of formative evaluation are equally relevant and indispensable at the micro-level for an enquiry into a particular tutorial or element of your teaching style. But we consider it of primary importance that you begin by building the time and opportunity for systematic evaluation into any and every curriculum development.

In that context, your focus as a teacher may be on any aspect of what is happening in the current iteration which can assist you to bring about improvement next time. Naturally, your first concerns will be the nature of the actual learning outcomes, and of the learning experience. You may want to know, for example, if your carefully designed computer-assisted learning (CAL) materials did lead to high post-test scores, or if the students do not manage to analyse as you have taught them, or if your examination does not test learning according to the learning outcomes you have set as your aims. Equally it will be helpful if an illuminative evaluation reveals the minor features of the CAL programme which have irritated or frustrated learners, and could be readily improved; or if it transpires tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- 1. APPROACHING CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT SYSTEMATICALLY

- 2. CHOOSING A METHOD OF FORMATIVE EVALUATION — AND USING IT

- 3. OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT THE IMMEDIATE LEARNING EXPERIENCE

- 4. OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT IMMEDIATE REACTIONS DURING THE LEARNING EXPERIENCE

- 5. OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT LEARNING OUTCOMES

- 6. OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT STUDENT REACTIONS AFTER THE EXPERIENCE

- 7. IDENTIFYING TOPICS THAT MERIT FURTHER EVALUATIVE ENQUIRY

- 8. FORMATIVE EVALUATION OF ASSESSMENT

- 9. ACTION RESEARCH AND ITS IMPACT ON STUDENT LEARNING

- Appendix Reminder sheets for colleagues who assist you

- References

- Further reading

- Index