- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Providing a framework to guide software professionals through the many aspects of development, Building Software: A Practitioner's Guide shows how to master systems development and manage many of the soft and technical skills that are crucial to the successful delivery of systems and software. It encourages tapping into a wealth of cross-domain and legacy solutions to overcome common problems, such as confusion about requirements and issues of quality, schedule, communication, and people management. The book offers insight into the inner workings of software reliability along with sound advice on ensuring that it meets customer and organizational needs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The awareness of the ambiguity of one’s highest achievements (as well as one’s deepest failures) is a definite symptom of maturity.—Paul Tillich (1886–1965)

Chapter 1

Failure

Fail better.—Samuel Beckett,

“Worstward Ho,” 1983

Civilizations perish, organisms die, planes crash, buildings crumble, bridges collapse, peaceful nuclear reactors explode, and cars stall. That is, systems fail. The reasons for failure and the impacts of the failure vary; but when systems fail, they bring forth images of incompetence. Should we expect perfection from systems we develop when we ourselves are not perfect?

All man-made systems are based on theories, laws, and hypotheses. Even core physical and biological laws contain implicit assumptions that reflect a current, often limited, understanding of the complex adaptive ecosystems in which these systems operate. Surely this affects the systems we develop.

Most people recognize the inevitability of some sort of failure although their reaction to it is based on the timing of the failure with respect to the life expectancy of the system. A 200-year-old monument that crumbles will not cause as much consternation as the collapse of a two-year-old bridge.

In software, failure has become an accepted phenomenon. Terms such as “the blue-screen-of-death” have evolved in common computer parlance. It is a sad reflection on the maturity of our industry that system failure studies, causes and investigations, even when they occur, are rarely shared and discussed within the profession. There exist copious amounts of readily available literature analyzing failures in other industries such as transportation, construction, and medicine. This lack of availability of information about actual failures prevents the introduction of improvements as engineers continue to learn the hard way by churning out fail-prone software. Before arguing that a software system is more complex than most mechanical or structural systems that we build, and that some leeway should be given, there is a need to look at the various aspects of failure in software.

A Formal Definition of Failure

Although the etymology of “failure” is not entirely clear, it likely derives from the Latin fallere, meaning “to deceive.” Webster’s dictionary defines failure as “omission of occurrence or performance; or a state of inability to perform a normal function.” It is important to note that it is not necessary that the entire system be non-operational for it to be considered a failure. Conversely, a single “critical” component failing to perform may result in the failure of the entire system. For example, one would not consider a car headlamp malfunction a failure of the car; however, one would consider a non-working fuel injection system as a failure. Why the distinction? Because the primary job of a car is conveyance. If it cannot do that, it has failed in its job. The distinction is not always so clear. In some cases, for example, while driving at night, a broken headlamp might be considered a failure. So how do we define software failures? Is a bug a failure? When does a bug become a failure? In software, failure is used to imply that:

■ The software has become inoperable. This can happen because of a critical bug that causes the application to terminate abnormally. This type of failure should never happen in an end-customer scenario. Most organizations have mandatory guidelines about QA (quality assurance) — that no software should ship to a customer until all critical and serious bugs have been fixed (see Chapter 12 on quality). All things being equal, such a failure usually signifies that there is a problem outside the software boundary — the hardware, external software interacting with your software, or some viruses.

■ The software is operable but is not delivering to its desired specifications. This may be due to a genuine oversight on the part of the development team, or a misunderstanding in the user requirements. Sometimes these requirements may be undocumented, such as user response times, screen navigations, or the number of mouse-clicks needed to fulfill a task. By our definition, a critical requirement must be skipped in development for the software to be considered a failure. Such a cause of failure points to a basic mismatch of the perceived criticality of needs between the customer and the project team.

■ The software was built to specifications but has become unreliable to a point that its use is being impacted. Such failures are typical when software is first released, or a new build hits the QA team (or the customer). There could be many small bugs that hinder the user from performing his or her task. Often, developers and the QA team tend to overlook inconsistencies in the GUI (graphical user interface) or in the presentation of data on screens. Instances of these inconsistencies include, but are not limited to the placement of “save” and “cancel” buttons, format of error messages, representation of entities across screens (e.g., “first name” followed by “last name” in one screen, and “last name, first name” in another). These cannot be considered bugs; rather, they are issues with a nuisance value in the minds of users, “putting them off” to a point that they no longer consider the software viable.

Failure Patterns

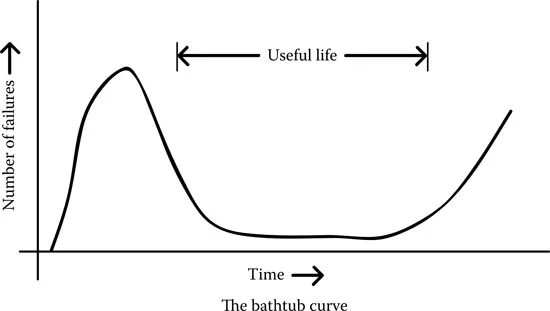

Failure as a field has been studied extensively ever since machines and mechanical devices were created. In the early days, most things were fixed when they were broken. It was evident that things would fail at some point in their lifetime, and there had to be people standing by who could repair them. In the 1930s, more studies were conducted, and many eminent scientists (including Waloddi Weibull) proposed probabilistic distribution curves for failure rates. The most commonly accepted is the “bathtub curve,” so called because its shape resembles a Victorian bathtub (Figure 1.1).

The first section of the curve is called the “infant mortality.” It covers the period just after the delivery of a new product and includes early bugs and defects. It is characterized by an increasing and then a declining failure rate. The second section, the flatbed of the bathtub, covers the usual failures that happen randomly in any product or its constituents. Its rate is almost constant. The third section is called “wear-out,” in which the failure rate increases as the product reaches the end of its useful life. In physical terms, parts of a mechanistic system start to fail with wear and tear.

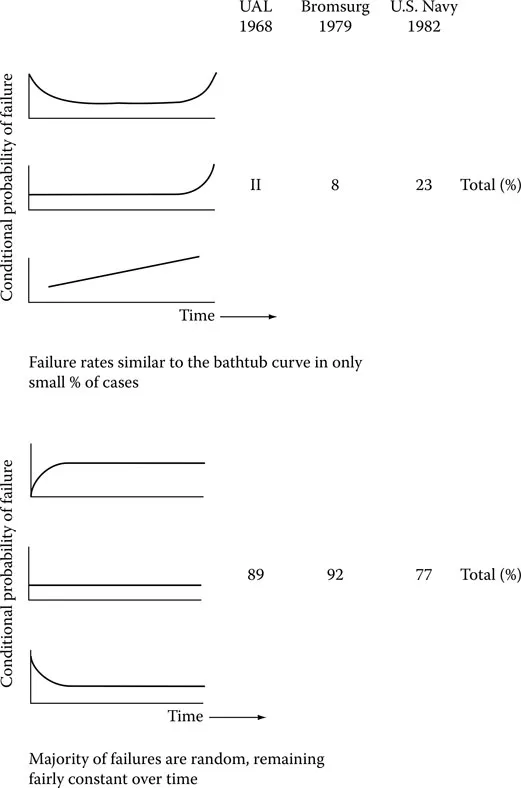

Until the 1970s, the bathtub curve remained the basis of scheduled maintenance for physical machines and production plants, where parts of such systems were regularly replaced regardless of their wear and tear. All this changed in 1978 due to the work of Nowlan and Heap. They worked with many years of data obtained from the airline industry and disproved the concept of a defined useful life in systems. Their studies revealed (Figure 1.2) that greater than 70 to 90 percent of all failures were random, leaving only a very small percentage of age-related failures. These failure patterns made it clear that scheduled maintenance could have the reverse effect on the life of a system. Any intrusion (part replacement) could potentially cause more damage because the system would reset to its infant mortality failure rate (which is higher) from its random failure rate. Nowlan and Heap created the concept of Reliability Centered Maintenance, a concept later extended to other systems by Moubray in 1997. His idea is that as more bugs and problems accumulate in a system, its reliability starts deteriorating. As experienced managers and engineers, we need to know when to schedule component replacements and perform system maintenance; and Chapter 12 (on quality) further discusses this.

The Dependability of a Software System

Dependability is a combination of reliability — the probability that a system operates through a given operation specification — and availability — the probability that the system will be available at any required instant. Most software adopts the findings of Nowlan and Heap with respect to failures. During the initial stages of the system, when it is being used fresh in production, the failure rates are high. “Burn-in” is a concept used in the electrical and mechanical industries, wherein machines run for short periods of time after assembly so that the obvious defects can be captured before being shipped to a customer. In the software industry, alpha and beta programs are the burn-in. In fact, most customers are wary of accepting the first commercial release (v 1.0) of a software product. The longer a system is used, the higher the probability that more problems have been unearthed and removed.

For most of its useful life, the usage of any software in the production environment is very repetitive in nature. Further, because there is no physical wear and tear, the rate at which problems occur does remain the same. The reality, however, is that during the course of its usage, there is a likelihood that the software system (and the ecosystem around it) has been tinkered with, through customizations, higher data volumes, newer interfaces to external systems, etc. Each time such changes occur, there is the chance that new points of failure will be introduced. As keen practitioners, one should be wary of such evolving systems. Make a call regarding the migration of the production environment (see Chapter 11 on migration). This call will be based on more abstract conditions than simply the rate at which bugs are showing up or their probability — it will depend on one’s experience in handling such systems.

Known but Not Followed: Preventing Failure

Software systems fail for many reasons, from the following of insufficient R&D processes during development to external entities introducing bugs through a hardware or software interface. Volumes have been written about the importance of and the critical need for:

■ A strict QA policy for all software development, customization, and implementation

■ Peer and buddy reviews of specifications, software code, and QA test plans to uncover any missed understanding and resource-specific flaw patterns

■ Adhering to documentation standards and following the documentation absolutely

■ Detailed end-user training about the system, usage, maintenance, and administration

■ Feedback from user group members who will interface with the system and use it on a day-to-day basis

■ Proper availability of hardware and software infrastructure for the application based on the criticality of its need

■ Frequent reviews, checks, and balances in place to gather early warning indicators about any untoward system behavior

There is little need to reiterate the importance of this list. The question one wants to tackle is: if these things are so clearly recognized, why do we continue to see increasing incidence of failure in software systems? Or do these policies come with inherent limitations because of which they cannot be followed in most software life cycles?

Engineering Failures: Oversimplification

Dörner, in his book entitled The Logic of Failure, attributes systems failure to the flawed human thinking process. Humans are inherently slow in processing various kinds of information. For example, while one can walk and climb stairs with ease (while scientists still struggle to remove the clumsiness in the walking styles of smart, artificial intelligence-based robots), one is not as swift in computing primitive mathematical operations such as the multiplication of two large real numbers. It is this apparent slowness that forces one to reduce analytical work by selecting one central or a few core objects. We then simplify, or often oversimplify, complex interrelationships among them in a system. This simplification gives one a sense that things are in one’s control and that one is sufficiently competent to handle them (Figure 1.3). On one hand, this illusion is critical for humans to maintain their profes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- About the Authors

- 1 Failure

- 2 Systems

- 3 Strategies

- 4 Requirements

- 5 Architecture and Design

- 6 Data and Information

- 7 Life Cycles

- 8 The Semantics of Processes

- 9 Off-the-Shelf Software

- 10 Customization

- 11 Migration

- 12 Quality and Testing

- 13 Communication

- 14 Reports

- 15 Documentation

- 16 Security

- 17 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix A Discussion of Terms

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Building Software by Nikhilesh Krishnamurthy,Amitabh Saran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Operations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.