1

ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE LABORATORY OF THE MIND

Thought experiments are performed in the laboratory of the mind. Beyond that bit of metaphor it’s hard to say just what they are. We recognize them when we see them: they are visualizable; they involve mental manipulations; they are not the mere consequence of a theory-based calculation; they are often (but not always) impossible to implement as real experiments either because we lack the relevant technology or because they are simply impossible in principle. If we are ever lucky enough to come up with a sharp definition of thought experiment, it is likely to be at the end of a long investigation. For now it is best to delimit our subject matter by simply giving examples; hence this chapter called ‘Illustrations’. And since the examples are so exquisitely wonderful, we should want to savour them anyway, whether we have a sharp definition of thought experiment or not.

GALILEO ON FALLING BODIES

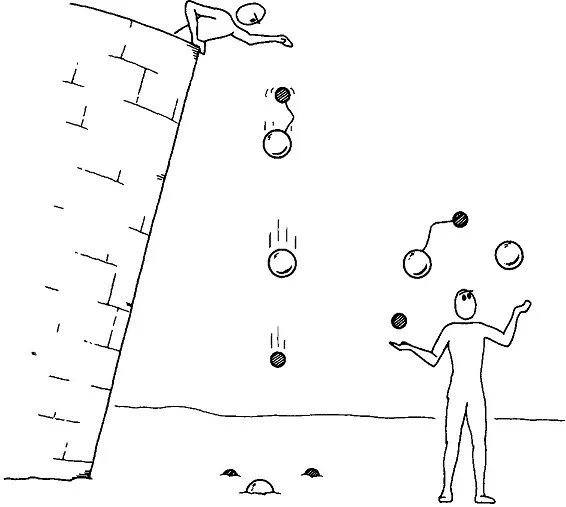

Let’s start with the best (i.e., my favourite). This is Galileo’s wonderful argument in the Discorsi to show that all bodies, regardless of their weight, fall at the same speed (Galileo, 1974, 66f.). It begins by noting Aristotle’s view that heavier bodies fall faster than light ones (H L). We are then asked to imagine that a heavy cannon ball is attached to a light musket ball. What would happen if they were released together?

Reasoning in the Aristotelian manner leads to an absurd conclusion. First, the light ball will slow up the heavy one (acting as a kind of drag), so the speed of the combined system would be slower than the speed of the heavy ball falling alone (H H+L). On the other hand, the combined system is heavier than the heavy ball alone, so it should fall faster (H+L H). We now have the absurd consequence that the heavy ball is both faster and slower than the even heavier combined system. Thus, the Aristotelian theory of falling bodies is destroyed.

Figure 1

But the question remains, ‘Which falls fastest?’ The right answer is now plain as day. The paradox is resolved by making them equal; they all fall at the same speed (H=L=H+L).

With the exception of Einstein, Galileo has no equal as a thought experimenter. The historian Alexandre Koyré once remarked ‘Good physics is made a priori’ (1968, 88), and he claimed for Galileo ‘the glory and the merit of having known how to dispense with [real] experiments’. (1968, 75) An exaggeration, no doubt, but hard to resist. Galileo, himself, couldn’t resist it. On a different occasion in the Dialogo, Simplicio, the mouthpiece for Aristotelian physics, curtly asks Salviati, Galileo’s stand-in, ‘So you have not made a hundred tests, or even one? And yet you so freely declare it to be certain?’ Salviati replies, ‘Without experiment, I am sure that the effect will happen as I tell you, because it must happen that way’.

Figure 2

What wonderful arrogance—and, as we shall see, so utterly justified.

STEVIN ON THE INCLINED PLANE

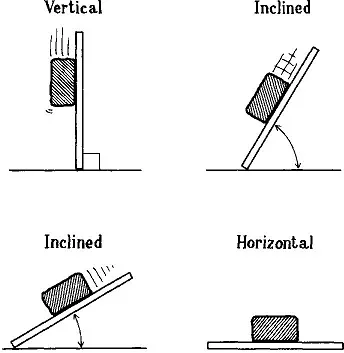

Suppose we have a weight resting on a plane. It is easy to tell what will happen if the plane is vertical (the weight will freely fall) or if the plane is horizontal (the weight will remain at rest). But what will happen in the intermediate cases?

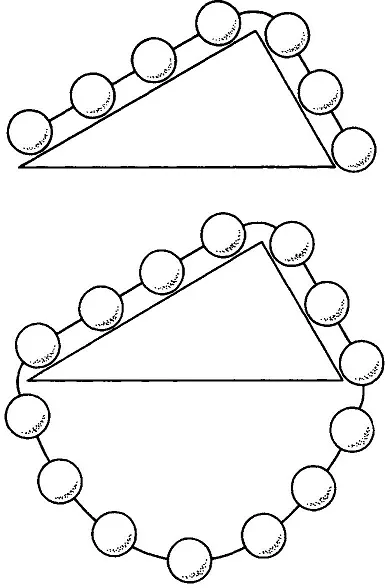

Simon Stevin (1548–1620) established a number of properties of the inclined plane; one of his greatest achievements was the result of an ingenious bit of reasoning. Consider a prism-like pair of inclined (frictionless) planes with linked weights such as a chain draped over it. How will the chain move?

There are three possibilities: It will remain at rest; it will move to the left, perhaps because there is more mass on that side; it will move to the right, perhaps because the slope is steeper on that side. Stevin’s answer is the first: it will remain in static equilibrium. The second diagram below clearly indicates why. By adding the links at the bottom we make a closed loop which would rotate if the force on the left were not balanced by the force on the right. Thus, we would have made a perpetual motion machine, which is presumably impossible. (The grand condusion for mechanics drawn from this thought experiment is that when we have inclined planes of equal height then equal weights will act inversely proportional to the lengths of the planes.) The assumption of no perpetual motion machines is central to the argument, not only from a logical point of view, but perhaps psychologically as well. Ernst Mach, whose beautiful account of Stevin I have followed, remarks:

Figure 3

Unquestionably in the assumption from which Stevin starts, that the endless chain does not move, there is contained

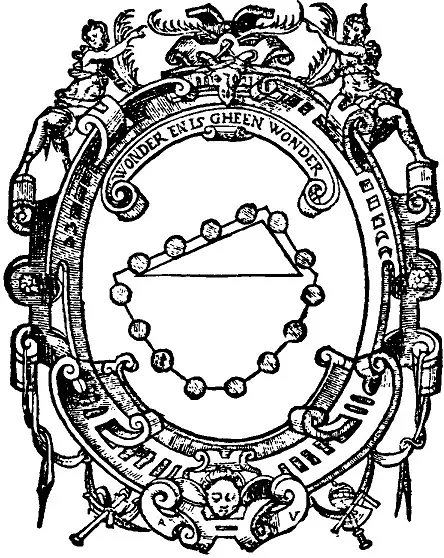

Figure 4 From the title page of Stevin’s Wisconstige Gedachenissen, more commonly known by its Latin translation Hypomnemata Mathematica, Leyden 1605.

primarily only a purely instinctive cognition. He feels at once, and we with him, that we have never observed anything like a motion of the kind referred to, that a thing of such a character does not exist…. That Stevin ascribes to instinctive knowledge of this sort a higher authority than to simple, manifest, direct observation might excite in us astonishment if we did not ourselves possess the same inclination…. [But,] the instinctive is just as fallible as the distinctly conscious. Its only value is in provinces with which we are very familiar.

Richard Feynman, in his Lectures on Physics, derives some results concerning static equilibrium using the principle of virtual work.

He remarks, ‘Cleverness, however, is relative. It can be done in a way which is even more brilliant, discovered by Stevin and inscribed on his tombstone…. If you get an epitaph like that on your gravestone, you are doing fine.’ (Feynman 1963, vol. I, ch. 4, 4f.)

NEWTON ON CENTRIPETAL FORCE AND PLANETARY MOTION

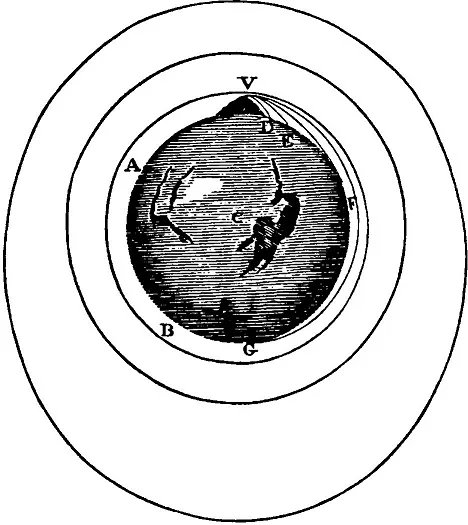

Part of the Newtonian synthesis was to link the fall of an apple with the motion of the moon. How these are really the same thing is brought out in the beautiful example discussed and illustrated with a diagram late in the Principia.

Newton begins by pointing out a few commonplaces we are happy to accept.

[A] stone that is projected is by the pressure of its own weight forced out of the rectilinear path, which by the initial projection alone it should have pursued, and made to describe a curved line in the air; and through that crooked way is at last brought down to the ground; and the greater the velocity is with which it is projected, the farther it goes before it falls to the earth. We may therefore suppose the velocity to be so increased, that it would describe an arc of 1, 2, 5, 10, 100, 1000 miles before it arrived at the earth, till at last, exceeding the limits of the earth, it should pass into space without touching it.

Newton then draws the moral for planets.

But if we now imagine bodies to be projected in the directions of lines parallel to the horizon from greater heights, as of 5, 10, 100, 1000, or more miles, or rather as many semidiameters of the earth, those bodies, according to their different velocity, and the different force of gravity in different heights, will describe arcs either concentric with the earth, or variously eccentric, and go on revolving through the heavens in those orbits just as the planets do in their orbits.

Figure 5

As thought experiments go, this one probably doesn’t do any work from a physics point of view; that is, Newton already had derived the motion of a body under a central force, a derivation which applied equally to apples and the moon. What the thought experiment does do, however, is give us that ‘aha’ feeling, that wonderful sense of understanding what is really going on. With such an intuitive understanding of the physics involved we can often tell what is going to happen in a new situation without making explicit calculations. The physicist John Wheeler once propounded ‘Wheeler’s first moral principle: Never make a calculation until you know the answer.’ (Taylor and Wheeler 1963, 60) Newton’s thought experiment makes this possible.

NEWTON’S BUCKET AND ABSOLUTE SPACE

Newton’s bucket experiment which is intended to show the existence of absolute space is one of the most celebrated and notorious examples in the history of thought experiments.

Absolute space is characterized by Newton as follows: ‘Absolute space, in its own nature, without relation to anything external, remains always similar and immovable. Relative space is some movable dimension or measure of the absolute spaces; which our senses determine by its position to bodies…’ (Principia, 6) Given this, the characterization of motion is straightforward. ‘Absolute motion is the translation of a body from one absolute place into another; and relative motion, the translation from one relative place into another’. (Principia, 7)

Newton’s view should be contrasted with, say, Leibniz’s, where space is a relation among bodies. If there were no material bodies then there would be no space, according to a Leibnizian relationalist; but for Newton there is nothing incoherent about the idea of empty space. Of course, we cannot perceive absolute space; we can only perceive relative space, by perceiving the relative positions of bodies. But we must not confuse the two; those who do ‘defile the purity of mathematical and philosophical truths’, says Newton, when they ‘confound real quantities with their relations and sensible measures’. (Principia, 11)

Newton’s actual discussion of the bucket is not as straightforward as his discussion of the globes which immediately follows in the Principia. So I’ll first quote him on the globes example, then give a reconstructed version of the bucket.

It is indeed a matter of great difficulty to discover…the true motions of particular bodies from the apparent; because the parts of that immovable space…by no means come under the observation of our senses. Yet the thing is not altogether desperate For instance, if two globes, kept at a distance one from the other by means of a cord that connects them, were revolved around their common centre of gravity, we might, from the tension of the cord, discover the endeavour of the globes to recede from the axis of their motion…. And thus we might find both the quantity and the determination of this circular motion, even in an immense vacuum, where there was nothing external or sensible with which the globes could be compared. But now, if in that space some remote bodies were placed that kept always position one to another, as the fixed stars do in our regions, we could not indeed determine from the relative translation of the globes among those bodies, whether the motion did belong to the globes or to the bodies. But if we observed the cord, and found that its tension was that very tension which the motions of the globes required, we might conclude the motion to be in the globes, and the bodies to be at rest.

Now to the (slightly reconstructed) bucket experiment. Imagine the rest of the physical universe gone, only a solitary bucket partly filled with water remaining. The bucket is suspended by a twisted rope—don’t ask what it’s tie...