- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Possible Worlds

About this book

Possible Worlds presents the first up-to-date and comprehensive examination of one of the most important topics in metaphysics. John Divers considers the prevalent philosophical positions, including realism, antirealism and the work of important writers on possible worlds such as David Lewis, evaluating them in detail.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Where possible-world talk is used

To show why philosophers find it congenial to talk in terms of possible worlds, I will begin by presenting in this chapter a picture of where such talk is used – this is a picture of what possible-world talk is supposed to elucidate or explain. The remaining chapters of the introductory section will be concerned with the fundamental philosophical issues that underlie possible-world talk. In Chapter 2, I will consider the different ways in which possible-world talk might be interpreted. There the central distinction is between realist interpretations that reflect acceptance of the existence of many possible worlds and antirealist interpretations that reflect resistance to that commitment. In Chapter 3, I distinguish the different kinds of elucidation or explanation – conceptual, ontological and semantic – that possible-world talk might be supposed to provide.

In seeking to cover the territory over which possible-world talk ranges in a fairly systematic and comprehensive way, I propose to divide it into three regions: the modalities (1.1), the intensions (1.2) and relations over intensions (1.3).1

(1.1) MODALITIES

The primary target of possible world discourse is modality. Philosophers typically recognize four central and interrelated cases of modality: possibility (can, might, may, could); impossibility (cannot, could not, must not); necessity (must, has to be, could not be otherwise); and contingency (maybe and maybe not, might have been and might not have been, could have been otherwise). The cases are standardly regarded as definitionally interrelated in the following ways. Possibility rules out impossibility and requires (exclusively) contingency or necessity. Impossibility rules out possibility, rules out necessity and rules out contingency. Necessity requires possibility, rules out impossibility and rules out contingency. Contingency requires possibility, rules out impossibility and rules out necessity.

Philosophers also recognize different kinds of modality. Charitable interpretation and appropriate context suggests that I might speak truly in making any of the following impossibility claims: ‘It is impossible that the number of chairs in the room is both even and not even’; ‘No one can both be married and be a bachelor’; ‘Michael could not have had any parents other than those he actually has’; ‘Nothing can travel faster than light’; ‘It can’t be the case that I don’t exist’; ‘A player cannot be in an offside position while in his or her half of the field of play’; ‘I won’t be able to keep our appointment this evening’; ‘You can’t pay people different rates for doing the same job just because one is male and the other female’. This intuitive variety of kinds of impossibility reflects that there are different kinds of consideration that exclude something from the realm of possibility. If the salient excluding considerations are logical (no proposition is such that both it and its negation are true) we might speak of logical impossibility. If the considerations are rooted in the meanings of words (nothing is both married and a bachelor) we might speak of analytic impossibility. Aside from the logical and analytic modality, contemporary philosophical interests also highlight metaphysical modality (fixed by the natures and identity conditions of things), nomological modality (fixed by the laws of nature), epistemic modality (fixed by what is known), doxastic modality (fixed by what is believed) and deontic modality (fixed by what satisfies a certain norm or rule). Yet, the picture seems naturally extendable so that we can recognize a kind of modality arising from any reasonably circumscribable set of considerations, no matter how trivial or parochial. Thus the truth of my saying that I won’t be able to keep our appointment this evening, may be grounded in the consideration that my keeping of the appointment fails to conform to or comply with my current set of actual social priorities and preferences. The salient kinds of modality are intuitively, but not uncontroversially, interrelated. It seems right to say that the laws of nature are in no position to permit what logic rules out. Thus, logical impossibility entails nomological impossibility. Yet even if the actual laws of nature rule out that a body should travel faster than light, logic appears to exert no such constraint. Thus, logical possibility does not entail nomological possibility.

Possible-world talk is invoked to elucidate these distinctions of both case and kind among the modalities.

We begin with the idea of the totality of the possible worlds across which all of the genuine possibilities (and no impossibilities) are represented. One of these possible worlds – the actual world – is special, closer to our hearts and distinguished somehow from the others that are ‘merely’ possible. Given this conception of a plurality of possible worlds, a modality of a given case and kind is characterized in terms of what is the case at a specified range of the possible worlds. In general, the M-possible worlds (logically possible worlds, analytically possible worlds, nomologically possible worlds, etc.) are those among the genuinely possible worlds that conform to or comply with the set of M-constraints (the laws of logic, the strictures of meaning, the laws of nature, etc.). Then, what is M-possible is true at some M-possible world; what is M-impossible is not true at any M-possible world; what is M-necessary is true at all M-possible worlds, and what is M-contingent is true at some but not all M-possible worlds. That basic characterization offers elucidation of the interdefinability of the cases of modality and their interrelations by way of principles governing the underlying quantifiers over possible worlds. For example, that necessity requires possibility is underpinned by the requirement that what is true of all (possible worlds) is true of some; that impossibility rules out necessity is underpinned by the requirement that what is true of none is not true of all. The basic characterization also promises elucidation of the interrelations between the kinds of modality. That nomological possibility entails logical possibility, for example, is reflected in a certain relation between the two sets of possible worlds. All of the nomologically possible worlds are logically possible worlds – the set of nomologically possible worlds is a subset of the logically possible worlds, the region of the logically possible worlds includes all the region of the nomologically possible worlds. That nomological necessity fails to entail logical necessity is reflected by there being a logically possible world that is not a nomologically possible world. It is not the case that all of the logically possible worlds are nomologically possible worlds (the set of logically possible worlds is not a subset of the nomologically possible worlds). It is a matter of controversy whether we can identify the collection of all the genuinely possible worlds with the collection that is circumscribed by any given M-specification. Thus it is controversial whether the collection of all (and only) the genuinely possible worlds can be identified with the logically possible worlds, or with the analytically possible worlds, or with the metaphysically possible worlds, etc.2 However, once we help ourselves to the idea of a collection of all and only the genuinely possible worlds which contains the actual world then, whether that collection is subject to more informative characterization or not, the modality that is captured by that collection of possible worlds is supposed to be both alethic and absolute. I now turn to these characterizations of the modalities and their possible-world elucidations.

As we have seen, various constraints that we take to hold over the actual world seem apt to be expressed in modal terms. But these constraints give rise to ‘musts’ that differ intuitively in various ways. Here is one such difference.

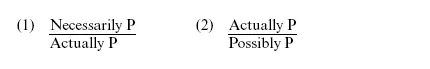

With the logical ‘must’ the relevant constraint holding over the actual world is a matter of non-modal truth (or falsehood) at the actual world. What logically must be true is actually true so that, for example, it is actually true that nothing is both green and not green. But with the moral ‘must’, for example, matters stand otherwise. Moral constraints that hold over the actual world do so in a way that is not directly reflected in non-modal truth (or falsehood) at the actual world. What morally must (or ought to) be true is (often) not actually true so that, for example, it is not true at the actual world that no one commits rape even though it ought not to be the case that anyone does so. In possible-world terms, we put the matter as follows. Corresponding to each world and to a set of constraints M, we have the set of M-possible worlds that conform to those constraints by having all of the relevant non-modal statements hold true at them. The alethic modalities are those kinds of modality for which the actual world is always one of the M-possible worlds that it generates: the constraints generated from the actual world are always satisfied by the actual world. All other kinds of modality are nonalethic. It follows from this brief characterization and from the earlier definitions of the various cases of modality that the following inferences are characteristically valid for the alethic modalities and invalid for the non-alethic modalities:

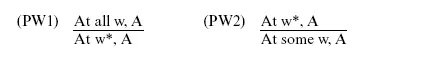

In possible-world terms, we infer in (1) what is true at the actual world from what is true at all M-possible worlds and we infer in (2) what is true at some M-possible world from what is true at the actual world:

The inferences will be valid, and so the relevant modality alethic, just in case the actual world, w*, is one of the M-possible worlds.

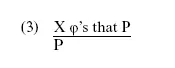

Among the kinds of modality that are usually reckoned to be alethic are the logical, the analytic, the metaphysical and the nomological. Prominent among the modalities that are usually reckoned to be non-alethic are the broadly deontic modalities – modalities that primarily guide action, prescribing what must, must not or may be done in order to satisfy certain precepts, norms or rules. Among the deontic subclass of non-alethic modalities are not only the moral modalities but legal modalities and other modalities of permission and obligation generated by various bodies of policy, codes of practice and sets of imperatives; drivers must not exceed 70 m.p.h., passengers may smoke on the upper deck and season tickets must be purchased in advance. Corresponding to these we have our classes of M-possible worlds from which the actual world may be absent in virtue of actual speeding drivers etc. The other major subclass of non-alethic modalities are those that correspond to the non-factive propositional attitudes – i.e. attitudes, φ, that do not sustain the validity of the inference:

Prominent among these is the attitude of belief and the associated doxastic modalities. The ‘might’ of a doxastic modality, to pick on one case by way of example, is what the belief system (of an individual, at a time) does not rule out. A doxastically possible world is one that conforms to my actual belief system by making it true. Similarly, a connatively possible world is one that conforms to my actual desires by making them come true. But since, no doubt, some of the things that I believe about the actual world are not true at the actual world, and since some of the things that I desire for the actual world will not come true at the actual world, the actual world will not number among my doxastically possible worlds or among my connatively possible worlds. However, for those special types of attitude that are factive, the related modalities are alethic. The factive status of knowing, reflected in the validity of the inference from my knowing that p to p, is reflected by the inclusion of the actual world in the class of all my epistemically possible worlds. For what I know to be true of the actual world is, invariably, true at the actual world. In the remainder of the book, I will be concerned almost exclusively with the alethic modalities.3,4

Within the range of the alethic modalities, I turn now to the possible-world elucidation of the distinction between absolute and relative modalities. Simply, a modality of kind M is absolute iff (i.e. if and only if) all and only the genuine possible worlds are M-possible worlds. Consequently, a modality of kind M is not absolute (it is restricted or merely relative) if there are some genuine possible worlds that are not M-possible worlds. What is necessary in only a relative or restricted sense is what holds throughout some proper subset of the genuinely possible worlds. Thus the genuine modality that is captured by the collection of all of the possible worlds is an absolute modality. The difficult questions, as indicated earlier, concern which kinds of modality should be accorded absolute status. In that matter opinion ranges from the austere position of identifying the unrestricted totality of possible worlds as those that are constrained only by the holding of the logical truths of some given logical system, through to the far more permissive position on which all logical, analytic, metaphysical and even some nomological modalities are absolute. For present purposes it does not matter which philosopher is right about where the line between absolute and relative modality should be drawn. What is important is that, due to the proliferation of modalities, all philosophers who take the modalities seriously will regard the distinction between absolute and relative modalities as non-trivial. The need to articulate the distinction is then served well by the distinction between unrestricted and restricted quantification over the genuine possible worlds. Finally on this point, the discussion of the distinction between absolute and relative modalities presents the best opportunity to mention one further aspect of possible-world talk that is congenial for certain purposes – talk of worlds being possible relative to others, or of worlds being accessible from others. To illustrate the point, let us think of the absolutely possible worlds as all and only those that respect first-order logic. What logic demands, then, does not change from possible world to possible world. There is no question of a claim being a logical truth at one possible world but a non-logical truth or even a falsehood at another. Because logical modality is absolute (we assume) in these ways, we may say that every possible world is logically accessible to and from every other possible world. Let us now take nomological modality as our example of a restricted or relative modality so that the absolutely possible worlds differ from one another with respect to the laws of nature that hold true at them. We may say then that a possible world w is nomologically accessible from a possible world v just in case all of the laws of nature at v are laws of nature at w as well.5 The relation of nomological accessibility is not an equivalence relation on the absolutely possible worlds. For example if all of the v-laws and some extra laws hold at w, then v is accessible from w but not vice versa, the accessibility relation is not symmetrical. It seems now that such definitions of accessibility relations, and such observations about the logical features of the relations promise some insight into questions about iterated modality that may otherwise seem doomed to intractability. Does it follow quite generally that something is possible from it being possibly possible? For a given univocal modality, M, the question may now be formulated as follows. If p is true at a world, w, which is accessible from a world, v, which is accessible from the actual world, is p thereby true at some world that is accessible from the actual world? If the accessibility relation is a transitive relation, as in logical accessibility, the answer is positive. If the accessibility relation is not transitive, the answer is negative. So thinking in terms of accessibility relations over possible worlds helps us to deal with questions of which principles of iteration are valid for various kinds of modality.6 In the remainder of the book I will be concerned almost exclusively with modality that is absolute as well as alethic, and all unqualified talk of modality is to be understood as such.7

(1.2) INTENSIONS

The wider modal territories include those of the intensions. The rough and ready idea is that entities of a kind are usually counted as intensional iff (a) they are associated with extensions in the actual world and (b) the associated extensions are not sufficient to distinguish what are intuitively distinct entities of that kind.8 Thus, it has been held, propositions are intensions (or intensional entities) since the extension of a proposition in the actual world is its truthvalue at the actual world and distinct propositions have the same truth-value at the actual world. The English sentences, ‘The Earth has several moons’ and ‘5 is the smallest odd prime number’ have the same truth-value, but (intuitively) do not express the same proposition. Equally it has been held that properties are intensional entities since the extension of a property at the actual world is the set of all and only the actually existing individuals that have the property, and one such set is the extension of distinct properties. The property of being human and the property of being a featherless biped have (we may presume) the same extension, yet they are distinct properties. It has also been held that states of affairs, events and other kinds of entity that we intuitively accept are intensional.

Talk of possible worlds promises philosophical illumination here through the proposal that intensional entities can be distinguished by appeal to divergence of extension across the totality of possible worlds. The basic and natural criteria of identity that are suggested by this strategy include the following: the same proposition is expressed by two sentences iff those sentences are true at exactly the same possible worlds; the property X = the property Y iff, at each possible world, all and only the individuals that have X also have Y. In that light, the thought goes, sentences such as those in our example – ‘The Earth has several moons’ and ‘5 is the smallest prime number’ – do turn out to express different propositions since there are possible worlds at which one is true and the other false. Equally, divergence in extension at some possible world – where there are featherless bipeds that are not human – ensures that being human is not the same property as being a fea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Genuine Realism

- Part III Actualist Realism

- Part IV Conclusion

- Notes

- Extended Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Possible Worlds by John Divers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.