- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is a work summarizing in one volume the pioneering approach of the author to public-interest decision-taking in the field of urban & regional planning. This book is aimed at students, researchers and professionals in planning. Nathaniel Lichfield first introduced in his "Economics of Planned Development" the concept that, in any use and development of land, the traditional "development balance sheet" of the developers needed to be accompanied by a "planning balance sheet" prepared by the planning officer or planning authority. Over the forty years since this work was published, the author has brought to the operational level the "planning balance sheet", with many case studies, primarily for consultancy purposes. The present title reflects the incorporation during the 1970s of the then emerging field of environmental impact assessment.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE: The nature of urban and regional planning

1.1 A concept of the urban and regional system1

No human settlement, except perhaps the remotest jungle-bound or desert village, is self-contained in that only residents use it. In contrast, the typical town is used in part by residents and in part by others who visit for various activities (work, education, recreation); and some of the town's residents will travel outside for some of their activities (work, recreation). Any town can thus be defined in relation to this functional crisscrossing of “urban activities”. This definition in itself must bring in the hinterland in which the town functions, i.e. its subregion. Together they make up the “urban and regional system”.

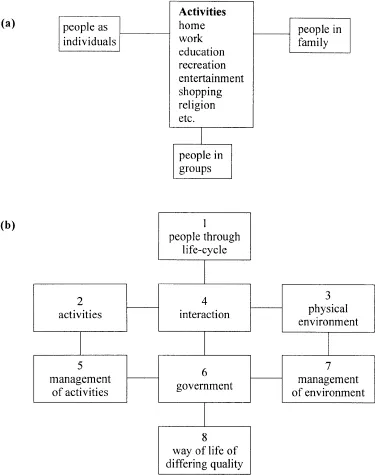

Any town or region thus comprises a diverse array of physical elements (buildings of all kinds and spaces between them, parks, roads) and of diverse human activities (shopping, production, recreation). In the diversity there is some order, for otherwise people would not get to work on time, would not have fresh milk available each morning, and would not meet in groups (religion, culture). Figure 1.1 a,b give one version of this order (see also Reif 1973, Wilson 1974, Batty 1976).

Within any community in the urban and regional system, from village to metropolis, each individual will participate in activities that will vary according to his/her stage in the life-cycle (Fig. 1.1a). Some of the activities will be purely individual, others as members of families, and others as members of wider-ranging groups (clubs, associations, youth organizations, etc.). In sum, the activities make up the way of life in the community, be it limited or full.

People, however, do not have full freedom in choosing their way of life; they are subject to external constraints over which they have little control, such as the economy or national policies. A concept of how a particular community achieves a particular way of life is shown in Figure 1.1b, to which the numbers in parentheses refer.

At the top of the Figure are the people (1), not at any one moment in time but as they change over their life-cycle. Their activities (2) require institutions (organizations and style of management) (5), ranging from highly centralized direction to considerable freedom for initiative, innovation or self-management.

People engaged in these activities have a physical environment, both natural and man-made (3), with institutions for their organization and management (7).

Figure 1.1 (a) Activity of people in a community through their life-cycle. (b) Way of life in community.

The physical environment (3) and activities (2) will interact (4). Correspondingly, the management of the activities (5) and environment (7) will interact with government (6). Good housing will help good family living. The absence of schools and community centres will stultify education and recreation.

All these influences will affect the way of life (8) and thereby people's perception of the quality of that life (Perloff 1969). They are concerned not simply with what they do but how they do it. In this a critical factor is the way in which that life is managed (5 and 7) and governed (6): the greater the degree of self-management, the greater the likelihood of people responding quickly to external changes and adopting solutions that suit their own perception of their needs and values. A high standard of life under a dictatorship is quite different in quality from a poor standard of life with freedom in law and self-management in an open democracy. A high standard of housing and landscaping can be coupled with a low level of personal fulfilment and poor-quality social relationships.

A high quality of life gives people, whether as individuals, families or groups, the opportunity to fulfil themselves as human beings. For this they need not only an appropriate material standard of life but also appropriate management of their environment in all spheres (social, economic, institutional, cultural, physical) and appropriate administration by government.

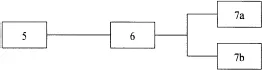

Figure 1.3 Change in the urban and regional system through a project

5. The urban project.

6. The system of activities and adapted spaces (Fig. 1.2, Box 3 and 4).

7. Post-project system of activities and adapted spaces:

(a) without government intervention;

(b) with government intervention.

1.2 Modelling the system

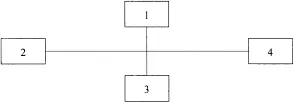

Of the many ways of modelling the urban and regional system, one that is well suited to our purpose is in Figure 1.2 showing Chadwick's framework “…within which the central relationship of Man and Nature can be seen clearly” (Chadwick 1978:19). The Figure shows how Man is part of the total ecosystem. Within this he differs from other animals in having a value system that influences the activities that make up individual and social life, and the capacity to adapt Nature and space to his needs, to both good and bad effect.

The systems in the Figure are “…a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes”, with the objects being parts or components of the system, the attributes being the properties of the objects, and the relationships tying the system together (Chadwick 1978:36).

But, while attempting to describe the real world, the system “…is not the real world, but a way of looking at it. Definitions of systems therefore depend in part on the purposes and objectives for which they are to be used” (McLoughlin 1969:79).

However, defining the system we wish to study is by no means easy since “…if we wish to consider the interactions affecting one simply entity, then we shall have to define that entity of the system. The system we choose to define is a system because it contains interrelated parts, and is in some sense the complete whole in itself. But the entity we are considering will certainly be part of a number of systems, each of which is a subsystem of a series of larger systems” (Beer 1966: ch. II).

Figure 1.2 Relationship of man and nature

1. The ecosystem: Nature, including Man and the natural landscape of the Earth and its flora and fauna.

2. Man's value system: values, goals, objectives.

3. Man's system of activities: activities, flows, abstract spaces.

4. Man's system of adapted spaces: adapted physical spaces, channels.

Source: Chadwick (1978).

Accordingly we need here to offer our own concept of the urban and regional system to suit our own purposes and objectives (McLoughlin 1969:79), bearing in mind that “…the recognition of a system does not necessitate or imply its complete description” (Chadwick 1978:9). In essence, our concept derives from our need in this book to explore the process summarized in Figure 1.3 to show how injections into the system (5) by projects (6) will bring changes into that system as it is evolving at any moment in time without planning intervention (7a); or how the changes can be shaped in accordance with such intervention (7b). It is the difference in the changes in the system represented by 7a and 7b whose impacts we are in effect aiming to evaluate.

1.3 A model of the urban and regional system2

Figure 1.1b shows the interaction between people's activity and their physical environment in a community. In this section we amplify that interaction.

Table 1.1 shows a representation of the urban and regional system that is suitable for our purpose. It is made up on the one hand of the supply of physical stock (col. 2) and, on the other, of the human population in their activities as producers and consumers in the socio-economic system (work, distribution, recreation, education) that exercise the demand on that stock (col. 3).

The physical stock can be divided into: natural resources and the man-made built environment, containing fabric and movables. The former comprise the human population inhabiting the land, water, minerals and so on, the product of the land (fauna and flora) and the life-giving air, sun, rain. The latter comprises both the infrastructure on which the utilization of the buildings and places depend: utility services (water, sewerage, gas, electricity); the means of transportation between buildings used for these various purposes (private automobiles, buses, trains); and also in substitute, the means of telecommunication between them (telephone, radio, television); and the buildings and open places used for residential purposes (homes, hotels, barracks) and for social activities (work, education, leisure, recreation).

The activities take place within the framework of Figure 1.1a,b. There is a flow of people to their activities, from within the town and surrounding area, who use the physical stock as producers and consumers: for part of the time they live in their dwellings (homes, hotels, etc.) and for part of the time occupy the buildings and places designed for social activities (work, recreation, leisure, education, etc.). As linkages between the activities there are the means of transportation and communication.

These activities take place within two physical frameworks which provide Man's total environment: Nature's ecosystem and Man's system of adapting spaces in the built environment (Fig. 1.2 above). His activities make their impacts upon this total environment, which in turn makes its impact on Man in an interacting impact chain (Ch. 7). It is the human impact on the natural environment which gives rise to human concern about the erosion of natural resources and environmental pollution, which in turn affect mankind in its daily life (smog, pollution of water for consumption and recreation).

Table 1.1 Stock in the urban and regional system, past, present and future.

Table 1.3 shows the situation at any moment in time past, present or future. Changes can be brought about by the interaction between the physical stock and human demands on that stock. Decline in the numbers of population and their requirements for work (Fig. 1.1b) will give rise to growth or decline in the numbers of dwellings, work places, etc. which are needed. These changes will come about not only from forces within an urban area but also from outside, in the particular region supporting a particular urban area, or in the wider system of urban areas of which the particular urban area is part (Rodwin 1970). Conversely, the availability or non-availability of a stock of man-made fabric of various kinds will attract to itself or deny human activities, as a stimulant or a constraint to socio-economic life.

It is through this interaction of the man-made fabric and human activities that cities, towns and villages change, grow and decline, through what is known as the development process. To this we now turn.

1.4 The adaptation of space through development process without government intervention3

The built environment typically comes into existence on open land which is used for some form of agriculture, or perhaps some transition between agricultural and urban use (for nursery gardens, storage of materials, etc.). The earlier use is displaced so that the vacant land becomes a development site. During construction, natural or man-made resources are destroyed, and environmental nuisance will arise (in noise, water, air). On completion of construction, the first life-cycle of the built fabric starts, with a use associated with the purpose for which it was designed (dwellings, manufacturing, retailing, etc.).

In the nature of the durable material typically used for human settlement, its life tends to be long, exceptions being the cane huts of an African village, tins and board of a Latin American squatter barrio, or the demountable tents of the nomadic Arab. This apart, the life will vary: relatively short (the ten years design life of “temporary housing”), or lasting over centuries (the monumental palazza of medieval Italy). By contrast, human activities which have to be accommodated within the fabric change much more rapidly (e.g. the size of families, modes of production, abandonment of cinemas for television, dislocation through war or earthquake). Thus, changes in human activities will tend in the first instance to be accommodated within the existing fabric, adapted as appropriate through refurbishment or other kinds of renewal, perhaps for a brief time and perhaps over a long period. At that time the physical stock reflects the then-current demands on it. But it may not do so later, following changes in location of activities or in means of accessibility of people to the physical stock.

Eventually the interaction cannot be quantitatively and/or qualitatively accommodated in the existing or adapted urban fabric, giving rise to the need for new physical stock on open land, either infill within the urban fabric or on its edge, which we call new urbanization. The adaptation of the current stock and the new development are in competition with each other in satisfying the common need for the matching of the fabric to contemporary requirements. The competition is not even, for the provision of new stock on open land is generally easier than renewal, in time, complexity and more profitable use of resources.

Over this life, the use and the conditions of the fabric, as a whole or in its separate parts, or within parts, do not remain constant. Maintenance and renovation lengthens physical life, but after a certain point, before it reaches exhaustion, the fabric becomes obsolescent. Then some form of renewal (in the form of rehabilitation or remodelling) is carried out, enabling the fabric to enter a new stage of life. This process will be repeated, once or more, before the degree of obsolescence is such that reconstruction, redevelopment or abandonment takes place. This is the beginning of a second life-cycle on the original site.

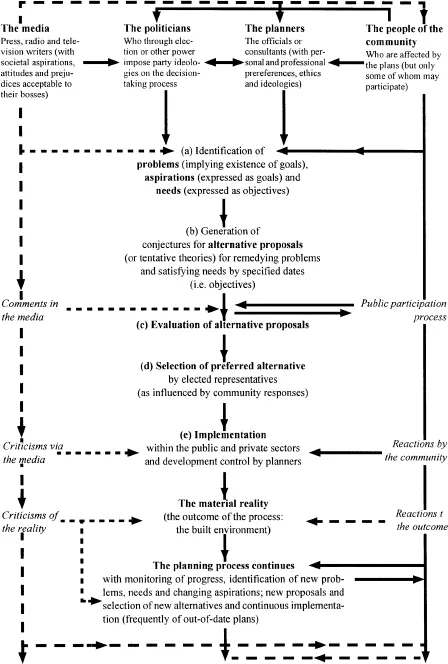

Figure 1.4 The planning process and those who may influence it (source: McConnell 1981).

But it could be that, instead of renewal taking place at the stage indicated, there is resistance because of the objectives of conservation of the fabric. In this case the process of renewal, and the uses that would flow from the works, would be different; conservation is a special kind of renewal.

All the adaptation of space over the life-cycle of the built environment, as just described, takes place within what is generally recognized as the urban development process (Lichfield 1956: ch. 1; Chadwick 1978:6– 11; Ratcliffe 1978: chs 5, 6; Baum 1982; Baum & Tolbert 1985; Cadman & Austin-Crowe 1993: chs 1–8). The process starts with the gleam in the eye of anyone who sees the potential for change and fin ishes when the completed construction is handed over for the occupation for which it was designed.

Such development can be seen as an economic process carried out by the Development industry, whereby an entrepreneur/undertaker/agency will bring together the various factors of production (land, labour and materials in the construction industry, finance) to produce the finished product to meet the economic demand which has been predicted. For this production/consumption process to be undertaken it is clearly necessary for the land itself to be appropriated (become property). As a result, there is a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Summaries

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- Chapter One: The nature of urban and regional planning

- Chapter Two: Choice, decision and action in everyday life

- Chapter Three: Evaluation for choice in land-use planning

- Chapter 4: The cost-benefit family in plan and project evaluation

- Chapter Five: Theory and principles of impact assessment

- Chapter Six: Theory and principles of cost-benefit analysis

- Chapter Seven: The generic method of community impact evaluation applied to projects

- Chapter Eight: Comprehending the conclusions of a CIE

- Chapter Nine: Simplification of the generic method

- Chapter Ten: Theory and principles of community impact evaluation

- Chapter Eleven: CIE in democratic planning

- Chapter Twelve: The planning process

- Chapter Thirteen: Roads: A case study comparing COBA, framework appraisal and CIE

- Chapter Fourteen: Development control

- Chapter Fifteen: Planning gain/obligation

- Chapter Sixteen: The cultural built heritage

- Chapter Seventeen: Integrating the environment into development planning

- Chapter Eighteen: Green belts

- Chapter Nineteen: Deregulation

- Chapter Twenty: CIE study management

- Appendix: Case studies in planning balance sheet and community impact analysis

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Community Impact Evaluation by Nathaniel Lichfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.