eBook - ePub

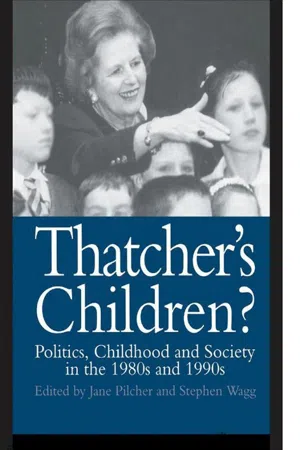

Thatcher's Children?

Politics, Childhood And Society In The 1980s And 1990s

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Thatcher's Children?

Politics, Childhood And Society In The 1980s And 1990s

About this book

That childhood is a social construction is understood both by social scientists and in society generally. The authors of this book examine the political issues surrounding childhood, including law making, social policy, government provisions and political activism.; This text examines current social and political issues involving childhood. It looks at the impact of the "New Right" who talk of family values, parent power in schools, irresponsible provision of contraception to young girls and the increase in child violence as a result of mass media. It also considers the response of the caring professions and the "Modern Left" who campaign, amongst other things, for the establishment of children's rights.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Thatcher's Children? by Dr Jane Pilcher,Jane Pilcher,Stephen Wagg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Thatcher’s Children?

Regarding Children

The French historian Philippe Aries first published his famous and important work Centuries of Childhood in 1959. Since then, sociologists around the world have, from time to time and with varying degrees of conviction, endorsed the book’s central tenet, namely that childhood is socially constructed and is, thus, specific to certain times and places in human history. On the whole, however, they have been reluctant to take the matter much further and, as recently as 1990, it was argued that the sociological study of children and childhood was in its ‘own infancy’ (Chisholm et al., 1990, p. 5). The criticism has been, not that there was a lack of research on children, but that the research which had been done was disproportionately concerned with the processes through which children became adults. It attended primarily to the development and socialization of children in families and schools. The notion that children were people —acting, reacting and helping to create their own social worlds—has taken longer to establish (see Alanen, 1992).

In recent years, however, new approaches to the social study of children and childhood have been emerging. In a seminal account, Prout and James (1990) have, in effect, set out a new paradigm for the sociology of childhood. This paradigm is more interpretative. It challenges notions of the natural or universal character of childhood and it assumes instead that childhood is processual and perpetually in flux, subject to the understandings and experiences of children in their specific social contexts (Prout and James, 1990, p. 15). Two features of this new approach are particularly important. Firstly, childhood is now seen as an institution which represents the ways, varying across time and cultural place, in which the biological immaturity of children is understood. Secondly, there is a concern to ‘give a voice’, albeit by adult mediation, to children as social actors who are themselves engaged in constructing and reconstructing this institution (Prout and James, 1990, p. 8).

Also central to the new view of childhood is the importance, following Foucault (Foucault, 1972), that is now attached to ‘discourse’—the concepts of children and childhood, the language through which these concepts are thought and expressed, and the social practices and institutions from which, ultimately, they are inseparable (Prout and James, 1990, p. 25). This concern with discourse defines the purpose of our book. Each writer has explored some dimension of the contemporary political discourses of childhood. While we accept fully the new view of children as active, reactive and creative beings, it would clearly be foolish to assume that they were active, reactive and creative in circumstances of their own choosing. Although, adapting Sartre, children will always make something of what is made of them, it is important, we feel, to look at the ways in which children have been framed, and their range of possibilities defined, in the dominant political language and practices of the late twentieth century.

During the 1980s and 1990s debates in Britain about social, political and economic affairs have been heavily circumscribed by the discourses of the New Right, which has made for a heightened public discussion of children and childhood. This discussion has taken place against a backdrop of important social and economic changes, which have been in train since the Second World War. For Alanen (1992, p. 6), these changes have brought a decreased significance of the traditional agencies of childhood (the nuclear family and the school) in relation to other agencies: child and youth services, the mass media and peer groups. It is the anxiety wrought by these changes that has found its most forcible and public expression in the discourses of the New Right. Indeed, children have often seemed to be at the heart of contemporary ideological wrangles. After all, in the most memorable political enunciation of the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher declared: ‘There is no such thing as “society”. There are men. And there are women. And there are families.’ The assumed children of these ‘families’ have often appeared in the rhetoric of the New Right to hover between Heaven and Hell. In Heaven, the male head of their nuclear family, doubtless an entrepreneur now liberated from state control and trade union interference, provides them with love, discipline and selective education. In Hell, children are menaced by a gallery of social demons: single mothers, absent fathers, muddleheaded social workers failing to detect abuse, drug pushers, paedophiles, ‘do-gooders’ reluctant to punish young offenders, ‘trendy’ teachers, doctors prescribing contraceptives for young girls, media executives purveying violent and sexually explicit material, and so on. Most of the chapters in this book are intended to go beyond these often lurid and melodramatic representations.

For, while commentators on the right have dominated political debates about childhood during the 1980s and 1990s, the left has nevertheless made its presence felt. Thus, while many among the New Right have foretold of a disintegration of childhood, many on the left have been exploring the possibility of extending the boundaries of childhood. Here long-established anarchist-humanist traditions seem to have combined with newer notions of empowerment to produce an active and influential children’s rights movement in several countries. In Britain, this manifested itself in successful campaigns on corporal punishment and bullying in schools, on child labour and on the rights of children both in local authority care and in hospital.

Thatcher s Children?

Although the book addresses other political discourses, Thatcher’s Children? acknowledges the key role played by the New Right in the mounting debate about children and childhood in the 1980s and 1990s. The political New Right was, as it remains, a broad and diverse grouping which cannot be reduced to a single party or government (Levitas, 1986); nevertheless, the Thatcherism of the 1980s can be seen as both heavily informed by, and an important variant of, New Right ideology (Smith, 1994; Hayes, 1994). Despite the departure of Margaret Thatcher in 1990, few would dispute the continued reverberation of Thatcherism as an identifiable cluster of arguments and assumptions in British political culture in the 1990s. Described by Kingdom (1992) as an ‘unstable amalgam’ of neo-liberalism—in relation to the economy—and authoritarian conservatism on moral questions, the discourse of the New Right has continued to characterize the Conservative administrations of John Major.

Both inside and outside parliament, debates about the family are one area where the morally conservative discourse of the New Right has been especially influential. For the New Right, the traditional, self-reliant, patriarchal nuclear family is the central social institution and the condition of the family serves, therefore, as an index of the moral well-being of the wider society (Moore, 1992). In New Right discourse, the liberal political consensus, which was forged in 1945 and which supported the interventionist state, is seen to have undermined the family, and with it the moral and economic health of the nation. Hence the stated determination of recent governments to re-establish the private sphere of the family—with patriarchal authority in regard to gender and generation—over the public sphere of the state. The apparent contradiction in New Right thinking between economic freedom, on the one hand, and social and moral authoritarianism on the other, can be resolved by seeing these two strands as aspects of a broader logic: ‘Individual freedom and choice were to be confined to the sphere of market relations, since in the social realm they had to rest upon a common cultural and moral foundation’ (Hayes, 1994, p. 89).

The central importance of ‘the family’ in New Right ideology, then, has been well established (Fitzgerald, 1983; David, 1986; Abbott and Wallace, 1989, 1992; Durham, 1991; Smith, 1994). However, the comparably important place in this ideology occupied by notions of children and childhood has come under considerably less scrutiny. So we hope in this book to add not only to the body of work done within the new paradigm of the sociology of childhood but also to the literature on the politics of the New Right. Each chapter of this book examines political discourse, practice and invocations of ‘the child’ in relation to an important social issue.

Stephen Wagg’s chapter looks at the post-war politics of British schooling, with particular reference to the period between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s. During this period, of which the Education Reform Act of 1988 is the major legislative landmark, children have been increasingly constructed in political discourse as passive. In this passivity, they have been seen principally as vulnerable (to ‘trendy’ or, latterly, merely ‘bad’ teachers) or as beneficiaries of their parents’ search for ‘good schools’ and ‘standards’. ‘Parent power’, the popular rallying cry of right-wing educational politics in Britain since the 1980s and the rhetorical seal set on the 1988 Act, is argued to have brought little genuine enfranchisement in the ‘new education market’. In the culture of this market, the term ‘child-centred education’ has become a straightforwardly pejorative one; nevertheless, as Wagg shows, efforts continue to be made to empower the British schoolchild.

As a number of contributors show in their respective chapters, children are mainly present in New Right discourse as instruments of wider political concerns about the condition of society—concerns which have included the relationship of the state to the private sphere, parental responsibility, support for ‘the family’, law and order and sexual morality. The chapter by Karen Winter and Paul Connolly addresses the apparent contradiction of the Children Act of 1989, in which a Thatcher administration, rhetorically steeped in patriarchal ‘family values’, legislated apparently to extend children’s rights. They show that, within the Act, these rights relate to their dealings with social service agencies, rather than with parents. Thus, the Act sits well with Thatcherite concern over the decline of ‘the family’ and the evils of state intervention.

Nigel Parton’s chapter also examines the 1989 Children Act, arguing that it represents a shift in the relations and hierarchies of authority between the different agencies involved in child protection. Child abuse, he suggests, is constituted not as a medico-social problem, as previously, but as a socio-legal problem. Parton’s central point is that, because of the extent to which child abuse is now perceived as a legal matter, too many cases are filtered out of the system, for lack of sufficient forensic evidence. Moreover, following media and public outcry at several killings of children by abusers (beginning with the death of Maria Colwell in 1973), child abuse has become an issue of publicity for the authorities. This, argues Parton, has strengthened official preoccupation with serious cases and left many other children in need of protection vulnerable. In short, the Children Act of 1989 has failed to solve the problem of balancing state intervention with the protection of privacy in these matters.

In the area of crime and young people, Tim Newburn notes that policy and practice during the ascendancy of the New Right has not been uniform. Here, despite militant declarations on ‘law and order’, early Thatcher administrations generally approved constructive, non-custodial work with young offenders. However, during the 1990s, in the face of proliferating moral panics about lawless youth and children out of control, there was a return to punitive custodial regimes for young offenders. This entails a new, or the return of an old, construction of the young offender—as someone who ‘knows what he’s doing’ and can only be deterred by tough discipline.

But, if young people know what they’re doing when they engage in crime, we cannot, according to New Right ideology, assume the same awareness on their

part if they choose to have sex. On this count, Jane Pilcher considers the moral eruptions over children and sex that have been a persistent feature of the 1980s and 1990s and studies in detail the implications of the so-called ‘Gillick Judgement’. She emphasizes the twofold paradoxical nature of the Gillick case: firstly, in that the Thatcher administration prevailed over the ‘moral lobby’; secondly, because the conceptions of childhood implicit in the final House of Lords judgment are at odds with New Right notions, both of the family and of the child. A review of the legacies of the Gillick case, however, reveals, as Pilcher concedes, that these paradoxes, especially in relation to children’s access to sexual knowledge and advice, are more apparent than real.

The fact that New Right campaigners such as Gillick have received less than full endorsement for their arguments from the courts must in part be due to the parallel strivings of the movement for children’s rights. A brief history of this movement, outlining its central ideas, debates, proposals and policies is provided by Annie Franklin and Bob Franklin. They, like Wagg in Chapter 2, note the largely unsympathetic response of leading politicians to initiatives on children’s rights. Successive Conservative governments in the 1980s and 1990s have disputed the need for a Commissioner for Children’s Rights, arguing that the Children Act of 1989 was sufficient to guarantee such rights. This means, as Franklin and Franklin point out, that, politically, the prevailing view is that children have rights of protection but not of participation.

Carey Oppenheim and Ruth Lister attend to a vital contradiction in New Right thinking on the family and childhood. They focus on policies to alleviate child poverty introduced by Conservative administrations in the 1980s and 1990s, with particular reference to the Child Support Act. Their analysis shows that during this period the self-styled ‘party of the family’ presided over policies that in many ways deepened the disadvantage of children and their families. Moreover, the Child Support Act, while purporting to reaffirm patriarchal family values and bind errant fathers to their parental responsibilities, in fact led to a channelling of money toward the Treasury and away from needy children.

Turning now to media discourses on childhood, Bob Franklin and Julian Petley assess newspaper reportage of the case of James Bulger. Press characterization of this killing of a small child by other children signals, they argue, a broader concern about children and contemporary childhood. Indeed, they find that, in a sense, British journalists used this occasion to reiterate the crude notions of ‘evil’ and individual culpability and to place in the dock the whole idea of extenuating social circumstance—a change of political mood discussed earlier by Tim Newburn. Franklin and Petley throw the distinctive nature of these dominant British attitudes toward child criminality into sharp relief by comparing them, firstly, to the treatment of similar cases in nineteenth-century Britain and, secondly, to the handling of a virtually identical incident in contemporary Norway.

In the following chapter, Pat Holland looks at the ways in which television now speaks to, and provides for, children and she discerns in these new modes of address a symbolic realignment in the relations between childhood and adulthood. This, she suggests, helps to make the relations between actual adults and actual children even more problematic. She also notes the incursion of the values of ‘childishness’ into adult media, arguing that this does not necessarily translate into a greater understanding of the needs of children. Indeed, we are still subject to intermittent moral panics about children’s relationship to the media, as new, often computer-related, forms develop children’s knowledge and skills in areas where many adults feel they cannot follow. Furthermore, this knowledge and these skills are being associated with dangerous pleasures, rather than learning or self-improvement, and are being honed in an increasingly deregulated commercial and media environment. Here, once again, we see vividly the clash between the values of the protective, patriarchal family and the free market ethos of economic liberalism.

A similarly stark reminder of this contradiction is provided by Michael Lavalette in his study of contemporary child labour. Lavalette contends that no meaningful distinction can be made between ‘children’s work’, a comparatively comforting phrase, and ‘child labour’, a term that suggests exploitation. At home and abroad there is clear evidence that the conditions dictated by neo-liberal economic policies have militated in favour of the oppression of child workers and against the preservation of ch...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Tables and Figures

- 1. Introduction: Thatcher’s Children?

- 2. ‘Don’t Try to Understand Them’: Politics, Childhood and the New Education Market

- 3. ‘Keeping It In the Family’: Thatcherism and the Children Act 1989

- 4. The New Politics of Child Protection

- 5. Back to the Future? Youth Crime, Youth Justice and the Rediscovery of ‘Authoritarian Populism’

- 6. Gillick and After: Children and Sex In the 1980s and 1990s

- 7. Growing Pains: The Developing Children’s Rights Movement In the UK

- 8. The Politics of Child Poverty 1979–1995

- 9. Killing the Age of Innocence: Newspaper Reporting of the Death of James Bulger

- 10. ‘I’ve Just Seen a Hole In the Reality Barrier!’: Children, Childishness and the Media In the Ruins of the Twentieth Century

- 11. Thatcher’s Working Children: Contemporary Issues of Child Labour

- 12. Child Prostitution and Tourism: Beyond the Stereotypes

- Notes On Contributors