Chapter I

A cautionary tale

Hello, I’m Clare—I’m just coming to the end of a three-year psychology degree, and I’ve been asked to write a few words about how I’ve coped with my dyslexia at college.

The first thing to say is that I’ve known ever since I can remember that I have dyslexic difficulties. I was assessed very early on at school and had some help and got extra time in examinations. By the time I reached the sixth form, I felt I was coping quite well with my difficulties and didn’t feel they hampered me too much. In fact, I tended to concentrate more on the positive sides of being dyslexic, like understanding things intuitively and being good at lateral thinking.

Anyway, when I got accepted at London University for a psychology degree, I just assumed I’d cope somehow. So I had a carefree gap year, travelling, working in the local wine bar and ignoring my parents’ advice to do some preliminary reading for my course.

When I arrived at college, I was pleased to find that my hall of residence was close to the main campus. So the first thing I did was to go out to explore—and the second thing I did was to get completely lost. I don’t have much sense of direction, and the buildings all seemed to look the same. I’d been given a map, but I had a problem understanding it. An annoying thing was that, even when I managed to find places, like the library, I would then lose them again.

After a week or so, I sort of got my bearings, and on the day that the first seminar was scheduled, I actually managed to find my way to the seminar room, at the right time, and to have the right books with me. It seemed like a good start.

There were about twelve of us at the seminar, and the subject was neuro-psychology, a word I didn’t really understand and could hardly pronounce. Anyway, it turned out to be about how the brain is wired up and which parts of it do things like speaking and listening.

As the tutor talked about this subject, I began to think that the listening bit in my brain couldn’t be working. The tutor kept explaining things, and other people were asking intelligent questions, but the whole thing seemed to be going right past me. I just wasn’t taking in what the tutor said. The upshot was that, at the end of the seminar, I had no more idea about neuro-psychology than I had at the beginning. I felt foolish and sort of inadequate, but I didn’t like to say that I hadn’t really followed anything.

Before leaving, the tutor gave us a list of journal articles to read for the following week’s seminar. She said the articles would make clear to us what brain processes were involved in the skill of reading. So the next day I went to the library and settled down to read the articles.

At this point it became clear to me that the bit in my brain that was ‘involved in the skill of reading’ had somehow also gone missing. As I read through the articles, I found I couldn’t really understand them. A lot of the words were long and unfamiliar, and it seemed to take an eternity just to read one article. The bit of my brain that did memory was obviously missing too, because I couldn’t remember anything about what I’d read. I sat in the library for hours that week trying to read the articles and getting more and more upset.

When the day of the next seminar came round, I felt a sense of dread. During the seminar, I was relieved that I wasn’t asked to say anything. Most of the other students had plenty to say or questions to ask, and there was a lot of general discussion. I just sat there not saying anything and not really following anything. All I could think about was: Why is all this so difficult for me? What has gone wrong?

But worse was to come. At the end of the seminar, the tutor set us an essay on reading mechanisms in the brain and suggested yet more articles we might want to look at. I won’t prolong the agony by trying to describe to you the torments I went through in trying to tackle this essay because ‘some of the events described might be too distressing to my readers’. All I will say is that, at the end of my first month at college, I was not having the marvellous carefree time I had anticipated. I was, as often as not, sitting depressed or crying in my room, feeling completely exhausted and wondering whether there were any parts of my brain that were actually functioning.

Perhaps I would have given up and just gone off the course, but, fortunately, in this darkest hour, rescue came to me in the form of Deborah, the dyslexia support tutor. I unexpectedly received an e-mail from her suggesting that we meet to discuss any difficulties I might be experiencing. Deborah hadn’t magically divined my despair; it’s simply that I’d ticked the dyslexia box on my application form without thinking much about it, and now she was following this up in a routine way by contacting me.

My meeting with Deborah marked the moment when things began to change for the better. At first I was quite emotional, sobbing and saying that I wouldn’t be able to cope. But Deborah calmed me down and assured me that lots of dyslexic students had major problems at the beginning of their course. She said she was sure I would cope once I got some help in place, and, meantime, she would let my tutors know I needed extra support. Basically, she said: just hold on, keep your nerve, things will get better.

She was right. I didn’t turn overnight into super-student, but I felt that I could see some way forward, some prospect of things improving, of not being alone with my problems.

Looking back, I’ve asked myself how it was that everything went so horribly wrong in those first few weeks. With hindsight, I think it was a combination of things. It would have been good if I’d followed my parents’ advice and had done a bit of preliminary reading during my gap year. I hadn’t done psychology for A-level, so all the vocabulary used was unfamiliar to me. I think a second problem was that when things did go wrong I didn’t ask anyone for help—I just went on trying to deal with the situation myself, perhaps thinking that, if I couldn’t, I was a failure. I think I also got quite frightened by the thought that I might actually not be able to continue the course. I didn’t have a Plan B.

Also, if I’m honest, I have to admit that it could have been partly the fact that I had been a little bit arrogant. I’d always prided myself on coping well at school, and I just assumed—wrongly as it turned out—that I’d easily be able to cope at university too. I just hadn’t anticipated how much more reading there would be, how much more pressure I would be under to do things quickly. Hindsight, as they say, is a great thing.

Anyway, I did cope in the end, thanks to all the support I received and, of course, through my own hard work. I did have to put in longer hours than most of my friends. The pay-off was that, by the second term, I had begun to actually enjoy my course, and now I feel it’s the best thing I’ve ever done. In fact, I’ve turned into an eternal student: I’m planning to go on to do a postgraduate course in neuro-psychology!

Chapter 2

Dyslexia and dyspraxia

In this chapter, I shall describe dyslexic difficulties and show how these overlap with a related set of difficulties, known as dyspraxia. I shall then explain how both dyslexic and dyspraxic difficulties cause particular problems with study skills. The chapter ends with a description of the talents and strengths which many dyslexic and dyspraxic people possess and which provide a valuable counterweight to their difficulties.

Dyslexia and dyspraxia explained

Most people feel that they cope well with some things but are hopeless at others. One person may struggle to write a letter but be easily able to build a house. Another person may be an academic high-flyer but socially inept. Yet another may be a gifted artist but unable to read a book.

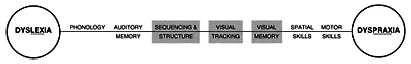

People who have dyslexic or dyspraxic difficulties tend to be inefficient in particular ways, and these areas of weakness can be shown on a continuum (see Figure 2.1). (All the terms used in the figure will be explained in detail below.)

Figure 2.1 The dyslexia–dyspraxia continuum.

A person described as dyslexic would certainly have weaknesses in phonology and auditory memory. They would probably also have difficulty with the middle three areas shown with shading, but not necessarily with spatial and motor skills.

A person described as dyspraxic would certainly have weaknesses in spatial and motor skills. They would probably also have difficulty with the middle three shaded areas, but not necessarily with auditory memory or phonology.

So, everyone has a different mix of difficulties, and the purpose of an assessment is to establish each person’s pattern of strengths and weaknesses.

Phonology

Phonology means the ability to recognise, pronounce, blend, separate and sequence the sounds of a language. So, people with poor phonological skills make mistakes in reading, spelling and pronouncing words (especially long words) and find it hard to read quickly or to read out loud.

Auditory memory

Auditory memory affects almost everything we do in life: thinking, speaking, writing, listening, remembering. In study, the following difficulties are common:

- following lectures, discussions and conversations;

- keeping track of your ideas when speaking to other people;

- remembering instructions and directions;

- concentrating for long periods;

- remembering names;

- remembering formulae;

- multitasking, e.g., listening and taking notes.

Sequencing and structure

Sequencing and structure help us to organise our lives in a logical and efficient way. We use them when we have a conversation, write a letter or an essay, listen to a lecture or plan our day. In fact, almost everything we do is structured in some way. Perhaps the only time we are not imprisoned within structures is when we are dreaming. So, difficulty with sequencing and structure affects the following:

- organising a work schedule;

- planning ahead;

- structuring ideas in oral presentations;

- structuring an essay;

- understanding written text;

- carrying out instructions in the correct order;

- filing documents and locating filed documents;

- looking up entries in directories and dictionaries;

- carrying out tasks in an efficient logical way.

Visual tracking

Visual tracking is a skill you use when you visually analyse a set of symbols. This could be a line of letters, or a line of numbers, or a more complicated visual image, such as a formula or equation, or a table of figures. So, poor visual tracking will cause problems in these areas:

- writing or copying numbers correctly;

- keeping numbers in columns;

- seeing the correct sequence of letters in a word;

- keeping your place on the page when reading;

- analysing maps, graphs, charts, tables of figures;

- reading complicated formulae or equations;

- setting out work neatly.

VISUAL STRESS

Some people report that they find it visually stressful to look at lines of print or dense patterns of any kind. They say that print seems to ‘jump about’ and that lines blur. They also find that white paper ‘glares’. Problems of this type are known as visual stress.

Visual stress is not part of a dyslexic syndrome but is often associated with dyslexia and adds an extra difficulty to reading.

For more information on this, (see page), and pages 64–5.

Visual memory

Poor visual memory causes problems with spelling irregular words; remembering material presented visually, e.g., mind maps; remembering where you have put things; and remembering where particular buildings are and which route you take to reach them.

Spatial skills

Spatial skills are required in any situation in which you have to judge distance, space or direction. Examples would be throwing a ball to someone, parking a car and telling left from right.

It may surprise you that spatial skills are also important in social situations. When you are with a friend, or at a social gathering, you need to judge the amount of ‘social space’ you need to leave between you and the person you’re speaking to. Dyspraxic people often report difficulty with this: they feel that they often talk too much or too loudly, that they tend to interrupt people and that generally they are not good team players.

Poor spatial skills are also often associated with poor judgement of time. This is not surprising given that we tend to see time as stretching out before us like space and, indeed, use phrases like ‘length of time’, ‘a long stretch’.

Motor skills

The term ‘motor skills’ means the skills we use when we plan and carry out physical movements. There are two types of motor skills: fine motor skills and gross motor skills.

We use fine motor skills for ‘small-scale’ tasks such as:

- handwriting;

- presenting written work neatly;

- using a word processor, calculator or telephone keypad;

- doing any task that requires good manual skill, e.g., woodwork, needlework;

- using laboratory equipment or scientific instruments.

We use gross motor skills for ‘large-scale’ tasks, such as playing sports or driving a car.

Poor motor control is the characteristic feature of dyspraxia. In addition to the problems mentioned above, dyspraxic people often have difficulties with balance: they tend to trip up or bump into things. They are also prone to spilling and dropping things.

Dyslexia and dyspraxia checklists can be found in

Appendix A.

These cover both study and everyday difficulties.

Positive aspects of dyslexia and dyspraxia

People vary in the way they feel abou...