- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design And Technology 5-12

About this book

Discusses how CDT fits into the primary curriculum and aims to assist teachers during the initial stages of introducing this type of thinking and making work. It explains basic concepts of DT, includes case studies covering work across the whole

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1: So Now It’s Design Technology

The activities of designing and making should be regarded as being, at the fundamental stage, every bit as

important as reading, writing andarithmetic, and at the more advanced stages, as important as literature,

science and history. Every child in every school, every year should be involved in designing and making

activity, on the grounds that, in its own right, it is a very valuable educational approach.

(Extract from the Stanley Lecture: A Coherent Set of Decisions—Sir Alex Smith, Royal Society of Arts,

London, 22 October 1980)

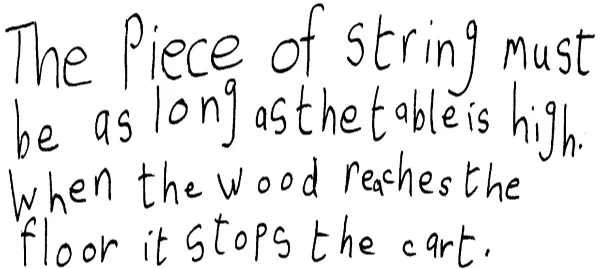

It seemed a very ordinary red car, the tissue box body with its wobbly wheels and the length of string tied to a piece of wood,

to be pulled along the ground no doubt. For the two six-year old boys who made it, it was a success. Success? Why? Was it

meant to do something in particular? Their two days work had been a journey of exploration and excitement, frustration and

achievement, because the ordinary red car represented the solution to a very precise design brief: to make an object which

would travel across a table top and stop at the edge. The red car now assumes a quite different significance, not just the

naively pleasing work of a young child, but a sophisticated, precise and appropriate response to a clearly identified problem.

So much is there: the shared experience of failure and reconsideration, because cardboard wheels not centred correctly won’t

travel and you do need an axle; the choice of an appropriate material—the tissue box was light and ready made; a genuine

understanding of the mathematical relationship between the length of the string and the height of the table, a basic

appreciation of the notion of force, the quick decision making and the wealth of linguistic opportunities. The children were in

no doubt as to the quality of the experience—It was good.

It would have been so easy to discount the value of what had taken place and yet it was so very real and relevant. It is this

reality and relevance which establish the place for design technology in the primary curriculum.

Primary education is constantly being challenged to achieve a further degree of ‘realism’ through the experiences it offers

children: the ‘feeling’ for mathematics identified by Cockcroft, writing for an identified audience, enjoyment as a respectable

criteria for learning to read. This realism is essential in a world which is rapidly changing as it identifies a kind of learning which

will have a lasting relevance. If this ‘realism’ is essential it must also be appropriate—and it is the appropriate design

technology experience which has so much to offer the individual and society.

Design Technology is about designing and communicating, making, testing and evaluating, encouraging children to go

beyond their first ideas and seek alternatives so that they may more effectively influence and control the environment in

which they live. In the primary school children will naturally tend to an investigative style of learning; their inventive urge is

not inhibited by pre-conceived notions of what is acceptable and the desire to communicate is very strong and urgent. They

are anxious to handle materials and to question processes. They are, in fact, beginning to develop a technological awareness.

Yet our attention is repeatedly drawn to the very limited opportunities which exist.

Experimenting with the little red car.

In the 1978 Primary Survey, attention was focussed on the limited materials in use in the primary schools and the lack of

development of skills in handling them. This concern was echoed in the 5–9 Survey (1982). Similarly, both surveys identified

little three-dimensional work.

The comparative neglect of three dimensional construction is disappointing: opportunities should be provided

for the older children, both boys and girls, to undertake some work with wood and other resistant materials and

to learn to handle the tools and techniques associated with them.

5.95 Primary Education in England (1978)

The number of classes involved in three-dimensional work was comparatively small and a limited range of

materials was used.

2.143 Education 5–9 (1982)

Both surveys urged the need for children to learn skills in context and they gave high priority to the development of problem

solving and thinking skills. Even within the opportunities which do exist, it is often possible for the activity to be presented in

such a way that its appeal is more immediately to boys than girls and play activities all too frequently reinforce sexstereotypes.

At the national level concerns of a similar nature exist. This country, which gave birth to the Industrial Revolution and led

the world of manufacturing industry, is now a net importer of manufactured goods. The ideas are there but the Department of

Industry recently found it necessary to mount an exhibition, ‘Designed in Britain, Made Abroad’; what is lacking is the

commitment to making. Applications to study applied sciences fail to show any significant increase. At the present time the

proportion of women engineers is something under 1 per cent, far less than other European countries. Attitudes are formed

early but change slowly and with difficulty. It is too late at secondary level to try to counter the vagaries of the educational

system and to reverse social pressures, but perhaps it is possible at primary level to change the emphasis so that ‘making’ is

accorded some status and the teaching opportunities provided by practical problem solving fully appreciated. This is not to

suggest that the role of Design Technology is simply to promote ‘education for capability’, of equal concern is the social and

cultural dimension it brings to the whole curriculum.

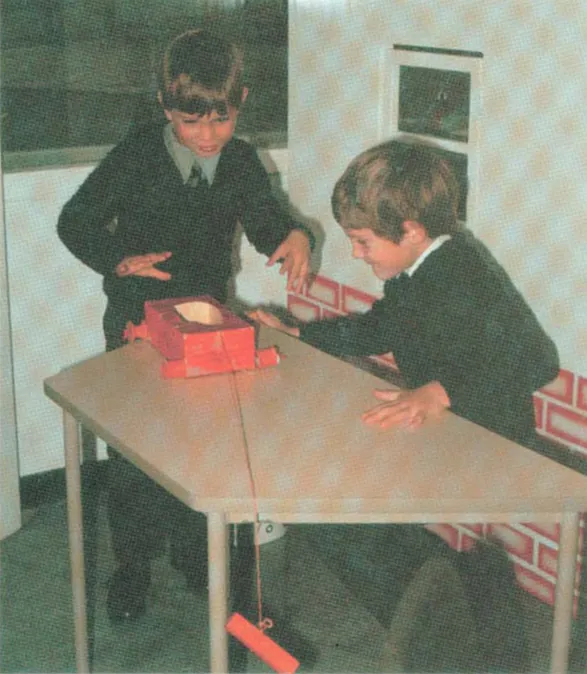

The Littlewick Licker—put a stamp on the tongue, turn the ears to wind on the tongue. Pour water in the top—it traves down a tube to the

back of the tongue. Wind out the tongue.

CDT helps to develop in people such qualities as imagination, inventiveness, resourcefulness and flexibility.

Industry and commerce need people with such qualities, but people as individuals also need these qualities in

order that they may be able to challenge and change their own roles in life if they so wish. —Equal Opportunities

in CDT.

If Design Technology is to develop within the primary curriculum then it undoubtedly presents a challenge, but it is a

challenge and not a revolution. It involves looking at what is already happening and putting it together rather differently. A

different emphasis will be necessary, particularly an acceptance that even the most basic of basic skills are best and most

readily learned within a relevant context. As David and Steven tried to find a piece of wood to pull their car across the table,

appropriate vocabulary developed: too big and too small were rapidly discarded in favour of heavier and lighter as the

distinction between size and weight was clarified. As leadership changed sides, styles of language altered. The teacher was

aware of the opportunities offered by the-design brief but, in one sense, could not control them since she could not predict the

children’s response. Her skill lay in appreciating the children’s need to handle and collect apparently rather aimlessly—until

the right piece of wood emerged; their need to find a book which showed how wheels went on a car, and when physical skills

were not adequate, their need for assistance in fixing the wheels. In all this activity the use of time is critical. Once

challenged, the child needs to complete his task. To break for a ‘phonic group’ or to read to Mrs. Jones perhaps says

something about the teacher’s perception of the value of the task.

A similar point was made in the 5–9 Survey:

While the children were drawing, painting or modelling, the teacher was busy helping children with work in the

base skills. Thus the educational value of art and craft was often not realised.

The challenge exists too in terms of classroom organization and the availability of resources. But the challenge is in essence

no different to that of organizing for practical experience in mathematics or science or working in groups for other activities.

What is essential is that the child has access to a variety of materials— wood, plastic, metal—and also the appropriate tools.

The appropriate plastic for the seven-year old may be the washing-up liquid bottle, but is he encouraged to identify and

appreciate its particular qualities and so learn to discriminate and choose the most appropriate material?

Outside the classroom an even greater challenge exists in developing the role design technology has to play in the primary

curriculum. It can clearly link and give meaning and relevance to many subject disciplines. Perhaps more important is the shift

in values and attitudes it can encourage away from only the academic to an appreciation of social and problem solving skills.

Design Technology offers a natural group activity—not the maths group busily occupied, each on the same page, but working

individually—an opportunity to ask other people for help in a most acceptable way and to respond to and modify their

suggestions in an attempt to provide an acceptable solution. In classrooms where so many ‘open-ended’ activities are in fact

so tightly fenced, Design Technology offers the child a real opportu nity to make decisions and to quickly appreciate feedback

both in terms of the solution and of its effect on the group.

And what of the teacher as the child delightedly explores the real world that he can actually influence? Uncertainty?

Hesitation? Perhaps inevitably this is so. Most teachers would very confidently rank pieces of written work according to the

chronological age of the child. How? By a series of professional judgements built up not just by themselves but by all the

teachers who have gone before. If pressed to explain the ranking they will refer, for example, to presentation, content,

sentence construction, and yet none of these criteria were expressed before the selection. In Design Technology no such body

of professional judgements exists. It will take time to develop a register of what is appropriate and perhaps we shall be

surprised by the ability we encounter—like the seven-year-old boy who had constructed a series of interlocking wheels and

could quite confidently predict the direction the speed in relative terms of any further wheel to be added—an understanding of

the concepts of gearing, ratio, drive—perhaps not quantified but quite clearly there. Technological development is taking

place in the normal curriculum but how well do we appreciate the level of understanding that primary children really have?

How many more red cars could we see?

DISCUSSION POINTS

- What ‘making’ activities exist within your school?

- Do these activities show a development as the children progress through the school in terms of materials; and skills?

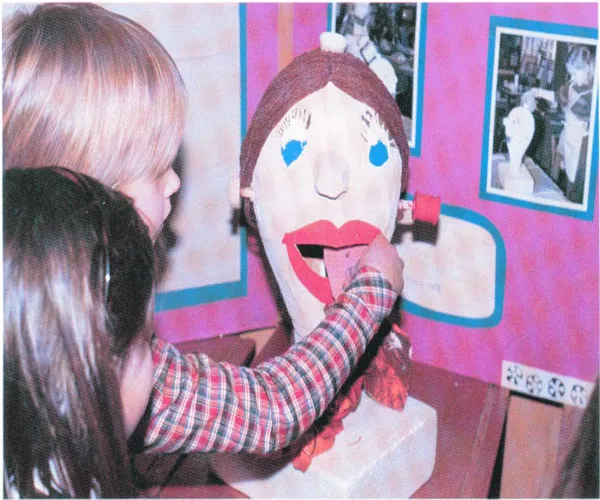

A roundabout made by infant children

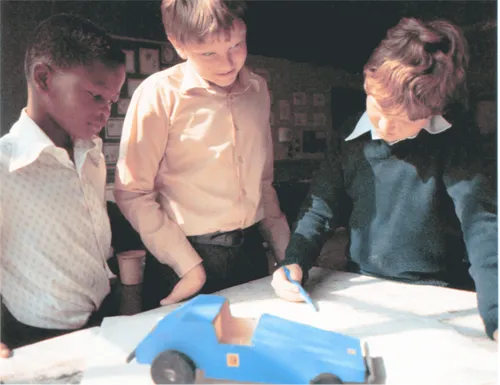

Looking for improvements—the decision must be made together.

2: Design Technology— Is it Appropriate at Primary Level?

What does a lessin look like? Sounds small and slimy. They keep them in glassrooms. Whole rooms made out of glass. Imagine.

Roger McGough

Craft Design Technology is developing in the secondary schools from the traditional practices of handicraft. It has a very distinctive philosophy—developing intellectual capacity and practical skills through designing and making. Craft Design Technology—a rather trendy title—and at first perhaps not appropriate for primary school, and yet it is through Design Technology which is very much in tune with the primary school ethos, that primary education can make a very relevant curriculum response to the 1980s.

If Design Technology is to develop in the primary school it must be seen to have a primary identity, one which will arise from the strengths and needs of the primary phase. Design Technology shares with the philosophy of primary education a commitment to three concepts: first hand experience, integration and process. Children of primary age are still in the business of collecting experiences which they are gradually learning to sift and order and between which to discriminate. The primary classroom strives to provide concrete first hand experiences and yet in a way these may be said to be contrived, at one step from reality. Design Technology cannot take place without an involvement with materials and this involvement is necessary and real. For the primary child knowledge is still largely a whole, subject disciplines are only gradually beginning to emerge, and discreet concepts still being formed. To solve a design problem work will stretch across the curriculum from planning skills, precise measurement, research skills to formal descriptive writing on craft work, each being brought into play as it becomes necessary. The need is identified by the child who quite clearly understands the purpose of the task he is engag...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Glossary of Terms

- 1: So now it’s Design Technology

- 2: Design Technology— is it Appropriate at Primary Level?

- 3: Where do You Put Design Technology in the Primary Curriculum?

- 4: Design Technology— What is it?

- 5: Design Technology—What Materials are Needed?

- 6: What do we Mean by Technology?

- 7: Design Technology: Successful Construction

- 8: Communication

- 9: Case Studies

- 10: Kits

- 11: Planning a Curriculum for Design Technology

- 12: Starting Points

- 13: Useful Addresses

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Design And Technology 5-12 by Patricia Williams,David Jinks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.