![]()

“It seems inevitable to me that some day, in an elegant new hi-tech museum, someone will holler out in recognition and affection: ‘Hey look, a whole room of Fischingers!’—or Len Lyes—or any of the great artist-animators of our century. They are the undiscovered treasures of our time.”

—Cecile Starr

The moving image in cinema occupies a unique niche in the history of twentieth-century art. Experimental film pioneers of the 1920s exerted a tremendous influence on succeeding generations of animators and graphic designers. In the motion picture industry, the development of animated film titles in the 1950s established a new form of graphic design called motion graphics.

| Precursors of Animation Early Cinematic Inventions Experimental Animation

Chapter Summary |

Precursors of Animation

1.1

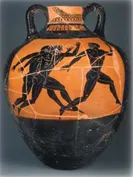

Panathenaic amphora, c.500 BC. Photo by H. Lewandowski, Louvre, Paris, France. Réunion des Musées Nationaux. © Art Resource, NY.

Since the beginning of our existence, we have endeavored to achieve a sense of motion in art. Our quest for telling stories through the use of moving images can be traced back to cave paintings found in Lascaux, France and Altamira, Spain, that depict animals with multiple legs to suggest movement. Attempts to imply motion were also evident in early Egyptian wall decoration and Greek vessel painting.

persistence of vision

Animation cannot be achieved without understanding a fundamental principle of the human eye: persistence of vision. This phenomenon involves our eye's ability to retain an image for a fraction of a second after it disappears. Our brain is tricked into perceiving a rapid succession of different still images as a continuous picture.

early optical inventions

Several individuals have been credited with the discovery of persistence of vision. They include Greek mathematician Euclid, Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, Roman poet Titus Lucretius Carus, British physicist Isaac Newton, Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau, and Swiss physician Peter Roget.

Although the concept of persistence of vision had been firmly established by the nineteenth century, the illusion of motion was not achieved until optical devices emerged. They appeared throughout Europe to provide animated entertainment. Illusionistic theatre boxes, for example, became a popular parlor game in France. They contained a variety of effects that allowed elements to be moved across the stage or lit from behind to create the illusion of depth. Another early form of popular entertainment was the magic lantern, a device that scientists began experimenting with in the 1600s (1.2). Magic lantern slide shows involved the projection of hand-painted or photographic glass slides. Using fire (and later gas light), magic lanterns often contained built-in mechanical levers, gears, belts, and pulleys that allowed the slides (sometimes measuring over a foot long) to be moved within the projector. Slides containing images that showed progressive motion could be projected in rapid sequence to create animation.

One of the first successful devices for creating the illusion of motion was the thaumatrope, made popular in Europe during the 1820s by London physicist Dr. John A. Paris. (Its actual invention has often been credited to the astronomer Sir John Herschel.) This simple apparatus was a small paper disc that was attached to two pieces of string and held on opposite sides (1.3). Each side of the disc showed an image, and the two images appeared to become merged together when the

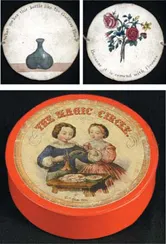

1.2

Magic lantern slide and projectors. Photos by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

disc was spun rapidly. This was accomplished by twirling the disc to wind the string and gently stretching the strings in opposite directions. As a result, the disc would rotate in one direction and then in the other. The faster the rotation, the more believable the illusion.

In 1832, a Belgian physicist named Joseph Plateau introduced the phenakistoscope to Europe. (During the same year, Simon von Stampfer of Vienna, Austria invented a similar device called the stroboscope.) This mechanism consisted of two circular discs mounted on the same axis of a spindle. The outer disc contained vertical slots around the circumference, and the inner disc contained drawings that depicted successive stages of movement. Both discs spun together in the same direction, and when held up to a mirror and peered at through the slots, the progression of images on the second disc appeared to move. Plateau derived his inspiration from Michael Faraday, who invented a device called Michael Faraday's Wheel, and Peter Mark Roget, the compiler of Roget's Thesaurus. The phenakistoscope was in wide circulation in Europe and America during the nineteenth century until William George Horner invented the zoetrope, which did not require a viewing mirror. Referred to as the “wheel of life,” the zoetrope was a short cylinder with an open top that rotated on a central axis. Long slots were cut at equal distances into the outer sides of the drum, and a sequence of drawings on strips of paper were placed around the inside, directly below the slots. When the cylinder was spun, viewers gazed through the slots at the images on the opposite wall of the cylinder, which appeared to spring to life in an endless loop (1.4).

The popularity of the zoetrope declined when Parisian engineer Emile Reynaud invented the praxinoscope. A precursor of the film projector, it offered a clearer image, overcoming picture distortion by placing images around the inner walls of an exterior cylinder. Each image was reflected by a set of mirrors attached to the outer walls of an interior

1.3

Thaumatrope discs and case. Photo by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of the Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

1.4

Zoetrope, top view. Photo by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of the Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

1.5

Praxinoscope views. Photos by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of the Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

cylinder (1.5). When the outer cylinder was rotated, the illusion of movement was seen on any one of the mirrored surfaces. Two years later, Reynaud developed the praxinoscope theatre, a large wooden box containing the praxinoscope. The viewer peered through a small hole in the box's lid at a theatrical background scene that created a narrative context for the moving imagery.

Early Cinematic Inventions

During the late 1860s, former California governor Leland Stanford became interested in the research of Etienne Marey, a French physiologist who suggested that the movements of horses were different from what most people believed. Determined to investigate Marey's claim, Stanford hired Eadward Muybridge, who had earned a reputation for his photographs of the American West, to record the moving gait of his racehorse with a sequence of still cameras (1.6). Muybridge continued to conduct motion experiments, some of which were published in an 1878 article in Scientific American. This article suggested that its readers cut the pictures out and place them in a zoetrope to recreate the illusion of motion. This fueled Muybridge to invent the zoopraxiscope, an instrument that allowed him to project up to 200 single images on a screen. This forerunner of the motion picture was received with great enthusiasm in America and England. In 1884, Muybridge was commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania to further his study of animal and human locomotion and produced an enormous compilation of over 100,000 detailed studies of animals and humans engaging in various physical activities. These volumes were a great aid to visual artists, helping them understand movement.

Muybridge's books, Animals in Motion (1899) and The Human Figure in Motion (1901), are available from Dover Publishers. Many of his plates are exhibited at the Kingston upon Thames Museum as well as in the collection of the Royal Photographic Society.

In 1889, Hannibal W. Goodwin, an American clergyman, developed a transparent, celluloid film base that George Eastman began to manufacture. For the first time in history, long sequences of images could be contained on a single reel. (Zoetrope and praxinoscope strips were limited to approxim...