![]()

1

THE RISE OF THE EAST ASIAN NEWLY INDUSTRIALISING ECONOMIES

An overview

The spectacular economic performance of the four East Asian economies – Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan – since the 1960s is by now well known. Success always attracts attention. As Krause (1985: 3) notes, ‘[t]here would clearly be much less interest in the four Asian Newly Industrializing Countries (NICs) if they had not been so remarkably successful. They led the world and in recent years they have grown twice as fast as Japan, the most successful industrial country in the post-war era.’ Several epithets have been used to dramatise this success. Woronoff (1986), for example, uses the term ‘miracle economies’. Other popular labels include ‘gang of four’ or ‘four little tigers’. A more neutral or generic term is ‘newly industrialising economies’ (NIEs) or ‘newly industrialising countries (NICs).

Ironically, it took nearly a decade for the development economics profession to become aware of the East Asian ascendency. The pioneers of the profession, such as Chenery, Higgins and Rosenstein-Rodan, writing in the 1960s, did not include the four little tigers as part of their list of economies most likely to succeed (Hicks, 1989). Perhaps Hughes (1971) and Myint (1969) were among the first few economists who took note of the phenomenon of East Asian success and drew attention to Singapore and Hong Kong. One could argue that a paradigm shift took place around the late 1960s and 1970 with such publications as Balassa (1968), Keesing (1967) and Little et al. (1970) – see Arndt (1987b). This framework was subsequently applied to explain the economic performance of East Asian NIEs in the latter part of 1970s (e.g. Little, 1979; Chen, 1979; Balassa, 1980, 1981).

It would be fair to maintain that since the late 1970s the success stories of Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan have become entrenched as part of the folklore of development economics. This book takes a fresh look at the voluminous literature on the East Asian NIEs and attempts to sift rhetoric from reality. A consistent effort is made to blend the country-specific experiences with broader themes in development economics. Within this broad objective, the specific purpose of this chapter is to provide an empirical overview of the rise of the East Asian NIEs. A useful way to start is to focus on the definition of the term NIE.

WHAT IS AN NIE?

There is no official definition or list of newly industrialising economies (Grimwade, 1989: 312). However, one can identify two broad aspects in the way the term is being used. The first, a comparative–static view, sees such economies occurring as an event in historical time and demarcates the phenomenon of industrialisation between pre and post Second World War. In that sense, countries which have been able to transform themselves in the post-war era into industrial economies where manufacturing plays an important role qualify as NIEs. Thus, Japan can be regarded as being the first of the post-war NIEs. They are ‘new’ in comparison with the ‘old’ industrialised countries of pre-war era. According to this view, industrialisation is a phenomenon, unique to specific conditions obtaining in particular countries at a particular point in time.

The second is a more dynamic and global definition and sees the emergence of the NIEs as an outcome of a changing world production structure corresponding to shifts in the international division of labour. To quote a leading author on the subject,

These changes occur as a result of a generalized historical movement in which industrialized countries vacate intermediate sectors in industrial production in which advanced developing countries are currently more competitive and advanced developing countries, in turn, vacate more basic industrial sectors in which the next tier of developing countries have a relative advantage. This view, then, sees the process of industrialization as one of historical spread in which the number of NICs will continue to increase.

(Bradford, 1982: 11)

How does one operationalise the definition of NIEs? Are there any quantitative criteria by which to classify economies at a particular point in time as NIEs? While there is some element of arbitrariness, the choice of criteria depends very much on the views one takes on development. For example, Turner (1982), working for the Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) has used the sole criterion of shares in world trade in manufacturing and reduced the list of NIEs to eight core countries: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and India. Although trade may unleash forces of dynamism, this view is a static one as is evident from the following quote:

To call such nations (Hong Kong’s status is still colonial) ‘NICs’ is to pass no judgement about how dynamic their economies currently are. Instead, we reflect the fact that these are the eight largest exporters of manufactures in the non-European developing world.

(Turner, 1982: 6)

Balassa (1980), working under the auspices of the World Bank, defines the newly industrialising countries (NICs) as developing countries that had per capita incomes in excess of $1,100 in 1978 and where the share of the manufacturing sector in the gross domestic product (GDP) was 20 per cent or higher in 1977. According to these criteria the NICs overlap with the upper ranges of the group of middle-income countries as defined in the World Development Report.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 1979) adopted a three-fold criterion to define a developing country as an NIE. Namely:

1 Fast growth in both the absolute level of industrial employment and the share of industrial employment in total employment.

2 A rising share of world exports of manufactures.

3 Fast growth in real per capita GDP such that the country was successful in narrowing the gap with the advanced industrialised countries.

Thus, the OECD (op. cit.) listed Spain, Portugal, Greece, Yugoslavia, Brazil, Mexico, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan as NICs. Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) works with a wider definition and also includes Israel, Malta, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand in the list of NIEs. The FCO also suggests to include Poland, Rumania and Hungary in the list of NIEs. Others even include India and Argentina.

While Balassa, the OECD and the FCO see the emergence of NIEs as a dynamic phenomenon, none emphasises the quality of their development. This stems from a narrow view of development, taken to be largely synonymous with economic growth. In contrast, a wider view of development is taken here and the emphasis is on qualitative aspects of growth. In other words, an NIE is defined by asking the question, ‘has the economic growth been associated with an enlargement of people’s choices?’ Thus, those developing countries are regarded as NIEs which have been able to break loose from the ‘vicious circle of poverty’ and ‘take-off from a ‘low level equilibrium’ to a path of continuous growth in living standard of their people. Therefore, a country must satisfy at least two conditions in order to be considered an NIE. First, it must take-off to a self-sustaining growth path. Second, there must be a sustained reduction in poverty and inequality and a continuing improvement in the standard of living. In short, these economies must achieve a certain level of ‘human development’ in the sense of ‘enlarged choices’ for their people.

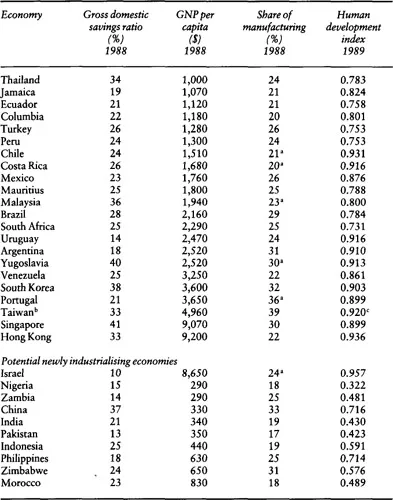

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (1990) has developed an index, known as the Human Development Index (HDI), to measure relative deprivation. It combines purchasing power, life expectancy and literacy for each of 130 countries and measures the relative position of each country with respect to the minimum and desirable values for the three. The index varies from zero to one in ascending order. Therefore, an HDI of 0.75 implies an above average human development in the sense of enlarged choices for the people.

According to the Nobel Laureate development economist W.A. Lewis (Lewis, 1965), a country reaches the take-off point once it converts itself from being a 4 or 5 per cent to a 12 or 15 per cent saver (investor). Tsiang and Wu (1985) have provided a theoretical basis for Lewis’ claim and, according to them, for a country to take-off, the savings ratio must exceed the capital/output ratio times the rate of population growth. Therefore, assuming an average capital/output ratio of 5 and a 3 per cent rate of population growth for developing countries, a country must achieve a savings/output ratio of 15 per cent or more to be able to graduate to an NIE.

There is a strong positive relationship between rate of savings and income per capita. A high domestic savings ratio can only be maintained if income per capita continues to rise. On the other hand, high savings and investment are essential for sustained income growth. Thus, once a country takes-off, the ‘law of cumulative causation’ implies that it should be able to transform the ‘vicious circle of poverty’ into a ‘virtuous circle of prosperity’.

Of course to be termed an industrialising country, manufacturing must play an important role. As a matter of fact, industrialisation has been vital for economic growth in most countries, except for those with small population and high concentration of natural resources. The patterns of structural change observed in developed and developing countries suggest that changes in the composition of GDP are extensive once the country has reached an intermediate income range ($300–$1,000 per capita). The expansion of manufacturing becomes very rapid in this phase and provides the impetus for structural change. In the emergent structure, the share of manufacturing in both GDP and employment will continue to grow, albeit at a slower pace once the country reaches an advanced stage (Ballance and Sinclair, 1983: 60). The share of manufacturing sector is found to rise rapidly once it reaches a critical level of 18–20 per cent (United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), 1979a).

While the borderline between categories is bound to be arbitrary, the above discussion enables us to lay down a four-fold criterion to statistically define an NIE. To be regarded as an NIE, an economy must have at least the following:

1 a savings ratio equal to 15 per cent;

2 a real GDP per capita equal to US$1,000;

3 a share of manufacturing in GDP and employment equal to 20 per cent;

4 an HDI equal to 0.75.

Using the above four-fold criterion, one can list twenty-two countries as NIEs (Table 1.1). The list is a snap shot at a particular point in time. In a dynamic context, the savings ratio, income per capita and the share of manufacturing in GDP must continue to rise and there must be a sustained improvement in human condition, measured by HDI. Failing to do so, a country will slip down the ladder and, at the same time, other developing countries may succeed in taking-off and join the group of NIEs. Over time, the successful NIEs will graduate to becoming fully fledged industrialised countries in their own right. Thus, ‘countries form a dynamic continuum in the development process. … [T]he borderline between advanced industrial countries and the NICs on one hand, and between the NICs and other developing countries on the other, is moving all the time and will always be a matter on which views may differ’ (OECD, op. cit.: 6).

Table 1.1 Newly industrialising economies

Sources: World Bank, World Development Report (various issues); UNDP (1990).

Notes: a 1980 figures.

b Asian Development Bank, Key Indicators.

c Own calculations, using the UNDP methodology.

There is considerable debate regarding the role of manufactured exports in industrialisation. This is because the nature of the relationship between the em...