- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by best-selling author Edward C. Luck, this new text is broad and engaging enough for undergraduates, sophisticated enough for graduates and lively enough for a wider audience interested in the key institutions of international public policy.

Looking at the antecedents of the UN Security Council, as well as the current issues and future challenges that it faces, this new book includes:

- historical perspectives

- the founding vision

- procedures and practices

- economic enforcement

- peace operations and military enforcement

- human security

- proliferation and WMD

- terrorism

- reform, adaptation and change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access UN Security Council by Edward C. Luck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Diplomacy & Treaties. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Context

1 Grading the great experiment

The Security Council is a special place. Over several centuries of institutional evolution, it is the closest approximation to global governance in the peace and security realm yet achieved. Its enforcement authority is unique in the history of inter-governmental cooperation. The UN’s 192 sovereign member states have agreed, under its Charter, to accept the decisions of the Council’s fifteen members as binding, despite ceaseless complaints about its undemocratic and unrepresentative character. Having survived more than six decades of hot and cold wars, its durability has proven unprecedented. As the centerpiece of the UN system, it is the depository of ageless dreams and recurring disappointments about the prospects for a more peaceful and cooperative global order.

Yet even the Council’s most ardent admirers have to admit that its track record in maintaining international peace and security – its mandate under the Charter – has been spotty at best. Surely nothing close to the dependable system of collective security sought by the UN’s far-sighted founders has been achieved. Clearly the Council has been more willing and able to grapple with some kinds of conflicts and with some regions than others. And the degree of consensus among its more influential members has ebbed and flowed, with the divisive debate in 2002–3 over the use of force in Iraq among its more public low points. So the Council appears to be caught in a historical limbo. Far more ambitious and accomplished than its predecessors, the Council’s performance nevertheless offers compelling testimony to the limits of global governance in an era of sovereign nation states.

All of this argues against sweeping endorsements or indictments of the Council’s place in the current and evolving world order. It also helps explain why the Council has proven to be such a lightning rod for commentary of all persuasions, as well as symbolic of so much that is right and wrong with the international system. Both sides in the debate over Iraq, for example, were quick to assert that they had the Council’s core purposes in mind, though they held starkly divergent images of what the Council’s role, place, and priorities ought to be. To those who believe that the Council’s first task is to decide when force can legitimately and legally be employed, it acted properly in denying the coalition seeking to oust Saddam Hussein’s regime its blessing. But for those who stress the Council’s responsibility for organizing collective action to enforce institutional law and norms, the episode capped a dozen years of equivocation and division in the face of Iraqi non-compliance.

This slim volume does not seek to decide such weighty debates or to pass judgment on the Council. Rather it aims to provide the reader with a sufficiently wide range of information, analysis, and historical background to understand and assess the Council’s place in past and contemporary efforts to bolster international peace and security. For those intent on weighing the merits of the Council’s work, it would be useful to begin by identifying some possible criteria for gauging the Council’s performance and potential. What standards are appropriate for weighing the value of a body that is historically unique both in its ambitions and in its legal and political authority?

At the basest level, it could be asked whether states are interested in participating in the Council’s deliberations and in influencing its decisions. The annual competition to be elected a non-permanent member, the lines of member states seeking to speak at open sessions, and the fierce, and seemingly endless, debate over ways to recast and broaden its composition suggest an affirmative response. Not only do states send their top diplomatic talent to represent them in Council deliberations, but, over the past dozen years, the Council has convened a number of times at the foreign minister or summit level, the latter most recently in September 2005 on aspects of terrorism.

Do states care, as well, about the content of the Council’s resolutions and presidential statements? In other words, do national political leaders look to the Council for more than photo-ops and political grandstanding on a global stage? Again, the protracted negotiations over the wording of sensitive resolutions – whether on Iran, Iraq, Palestine, the Balkans, or the mandate for a new peacekeeping force – suggest that this content matters for reasons of law, politics, and policy. The very act of bringing a matter to the Council, such as efforts by Iran and North Korea to acquire nuclear weapons, or Syrian involvement in Lebanon, is considered by the parties involved to be a serious and consequential step. Once a contentious case is before the Council, the major powers are rarely shy about bringing pressure to bear in the capitals of undecided non-permanent members. Words often matter. Despite all of the ups and (mostly) downs of the Middle East peace process, for example, the wording of resolution 242 of 1967 – and differing interpretations of it – still is cited by the parties as a critical plank in any formula for a durable peace in the troubled region.

On the other hand, even if the Council is central to the life of international diplomacy, what evidence is there that its words and actions matter to ordinary people, to the work of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and to the media? Realists, after all, have long dismissed the work of the Council as marginal, at best, to the course of power-based politics in a largely anarchical world.1 Indeed, for much of its life, constrained by the tensions of the Cold War, the Council had relatively few opportunities to make a difference. So publics and journalists looked elsewhere for the seminal events of the day. Many news outlets closed or severely trimmed their UN bureaus. Now some of the action is returning to Turtle Bay. The Council’s growing activism since the end of the Cold War has spurred renewed interest among the public, press, and pundits, if not always their approval.

The political fallout from the Council’s bitter and ultimately indecisive debate over the use of force in Iraq included declining public confidence in the UN, according to various opinion surveys, in a broad range of developed and developing countries.2 While not encouraging for the world body, the results confirmed that publics were neither disinterested nor uninformed about the Council’s struggles to find common ground on how to deal with the crisis. What was most striking was the degree to which people throughout much of the world had come to accept the premise that the Council’s authorization was either mandatory or highly preferable prior to the use of force. Even for a Bush administration once dismissive of the UN’s relevance, the goal of getting the Council on board, both before and after the use of force in Iraq, appeared to be a high priority. Hardheaded realists should take note, for something is changing in terms of international norms and public perceptions regarding the rules of warfare, the use of force, and sources of legitimacy. The Council’s boosters, on the other hand, should beware that public expectations concerning the Council’s performance may well be rising with its increasing activism.

While this quick review argues that the Council does matter at the level of political relevance, steeper tests would ask whether it has succeeded (1) in eliciting substantial and sustainable commitments from member states to support its decisions; (2) in carrying out its operational activities and missions competently and efficiently; and, ultimately, (3) in making a real difference to the maintenance of international peace and security. Should the Council be deemed to have surmounted all of these hurdles, a final question of comparative advantage would remain. Has the Council been the best placed vehicle for pursuing some set of core international security goals?; if so, which ones?; and which should be left to others or be addressed in partnership with other groups and institutions?

There are any number of ways to measure member state commitment to carrying out Security Council resolutions. One would be whether they have altered their policies in substantial ways to conform with Council edicts on important matters. Have they faithfully and fully implemented, for instance, sanctions regimes approved by the Council, whether related to diplomatic, political, economic, social, or arms control activities? Another set of measures would consider the material, political, and human assistance states have provided for Council-mandated missions, whether of a humanitarian, peacekeeping, or enforcement nature. While most peacekeeping operations are funded through assessed contributions, humanitarian, nation-building, and enforcement actions generally need voluntary contributions, human as well as financial. Since member states retain their sovereignty under the UN Charter, compliance, cooperation, and participation are not automatic (even if expected under Article 25). They require action within national capitals, and the response rate obviously varies greatly by country and issue. Whether the commitment glass should be considered to be half full – filling or ebbing – would no doubt depend on where and when one looks. The glass, moreover, is itself expanding as the Council takes on new issues and asks more of the member states (see Part III, on challenges, below). The pull of Security Council decisions, especially binding ones under Chapter VII of the Charter, on national capitals has surely been more than negligible given the vast quantity of money, soldiers, and effort – now including reporting – that has been devoted to Council-sponsored activities and operations over the years. But, as the chapters that follow attest, the unevenness and selectivity of member state responses to Council appeals have been equally impressive.

Has the Council gone about its ambitious work in an efficient and productive fashion? The UN’s management reforms of the last decade have put considerable emphasis on instituting modern management techniques, such as results-based budgeting, a more flexible human resources system, an inspector general’s office, lessons-learned and best practices units, and cross-sectoral integration of planning and operations. Much has been achieved, yet the oil-for-food scandal underlines how very far there still is to go. The Council itself has undertaken a series of reforms of its working methods in the name of greater transparency and accountability, even as deeper reforms in decisionmaking and composition have been resisted.

How can the competency and efficiency of efforts to advance peace and security be measured, given the moving targets, the raft of unknowns and hypotheticals, the indefinite timeframes, the vagaries of politics, and the preference for prevention over cure? How does one account for tragedies avoided? Is it a sensible expenditure of resources, for example, to maintain a peacekeeping force in Cyprus for over forty years, or of political capital to devote so much of the Council’s time and attention to the more intransigent aspects of the Middle East crisis? Should the Council devote more resources to those crises most ripe for solution or to those with the most troubling implications? Are there times when conflict can produce constructive change and the Council should step aside and let history follow its own course? How does one introduce factors of efficiency and productivity into the deliberations of such an intrinsically political body? Where one stands on such questions depends largely, of course, on where one sits. And yet how can such considerations not be taken into account when political, financial, and military resources are in limited supply?

Surely the first rule for the Council, as for the medical profession, should be to do no harm. Sometimes, as in Srebrenica and Rwanda, its unprincipled neglect had tragic consequences. The Council is unhelpful, at best, when it raises false expectations with rhetorical flourishes or paper-thin deployments, or adds layers of polarizing global politics to local ones. In East Timor, Central America, West Africa, Southern Africa, and Southeast Asia, on the other hand, most would agree that it has made a positive, and often pivotal, difference. In reviewing the issues raised in the following chapters, one would do well to keep asking where, when, and why the Council has – or has not – been able to achieve positive results. In particular, to what extent might lessons learned from past experience help or hinder the UN’s understanding of how to address the emerging challenges of human security, failing states, terrorism, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction? Likewise, what do such lessons tell us about which reform steps might boost or hinder the Council’s capacity to make a difference in the future?

Finally, it should be asked, relative to each of the policy tasks addressed in this volume, whether the Security Council is the best placed and equipped organ for dealing with the problem at hand. Under Chapter VIII of the Charter, it is envisioned that the parties to a conflict themselves should endeavor to resolve their differences peacefully, that the involvement of regional arrangements would be a second recourse, and that referral to the Council would be undertaken when a resolution of a crisis could not be managed at these lower levels. While the employment of enforcement measures could only be authorized by the Council, it was contemplated that regional cooperation would ease much of the burden on the Council for maintaining international peace and security. The founders, in this regard, seemed to be early proponents of the principle of subsidiarity, in which policy issues are to be resolved at the lowest responsible level. Successive secretariesgeneral, moreover, have asserted that the UN is not capable of organizing or overseeing military enforcement measures, which must be left to coalitions of the willing. In operational terms, the doctrines of subsidiarity and of coalitions of the willing may be eminently sensible, but they fit awkwardly with the assertion elsewhere in the Charter that the ultimate legal authority for the use of force resides in the Council.

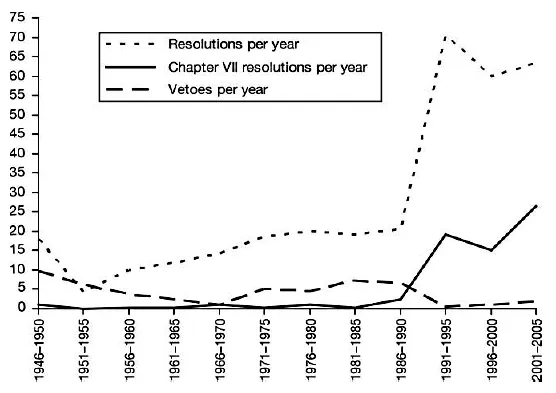

Before turning to the founders’ hopes, dreams, and expectations, much less to an assessment of the Council’s performance to date, two further caveats should be borne in mind. One is that there are problems without solutions, or at least without any feasible or cost-effective answers in a reasonable time-frame. Member states habitually bring just such problems to the Council. As noted above, the Charter stipulates that the Council is not expected to handle every crisis, only those that no-one else can resolve. The second is that the world changes, and with it the prospects for successful Council action. It is not coincidental that the Council moved in slow motion for four decades of Cold War and has been hyperactive since its end. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the rate at which it managed to pass resolutions and, importantly, Chapter VII enforcement resolutions, accelerated exponentially following the Cold War, even as the number of vetoes cast precipitously declined.

Clearly, the Council is not above the vagaries of international politics. Indeed, it is all about politics: local, national, regional, and global. The story of the Council, in other words, is a narrative on the evolution of global geopolitics. But the Council is more than just a barometer, it is also an actor that seeks to change the course of human events, even if incrementally and imperceptibly.

Figure 1.1 Average number of Security Council resolutions, Chapter VII resolutions, and vetoes per year for each five-year period 1946–2005

Sources: www.un.org/documents/scres.htm.; Sydney D. Bailey and Sam Daws, Procedure of the Security Council (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

2 The founding vision

Old council, new council

Of one thing, the proponents of the infant United Nations were absolutely certain: the new world body would be a very different animal than its predecessor, the League of Nations. It would have to be if it was to deliver on the opening pledge of its Charter “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetimes has brought untold sorrow to mankind.” The League had, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov reminded the opening plenary of the UN’s founding conference in San Francisco,

betrayed the hopes of those who believed in it. It is obvious that no one wishes to restore a League of Nations which had no rights or power, which did not interfere with any aggressors preparing for war against peace-loving nations and which sometimes even lulled the nations’ vigilance with regard to impending aggression.1

Yet in many respects the shape and structure of the new organization bore an uncanny resemblance to those of the old one. As the League’s foremost chronicler, F. P. Walters, phrased it:

As the new [UN] organizations took shape, each absorbed in one form or another, the functions, the plans, the records, and in many cases the staff, of the corresponding organ of the League. In the wider vision of a time of rebirth, and with the additional confidence, initiative, and resources supplied by the adhesion of the United States, most of the new agencies were able to start their career on a scale which those of the League could never attain. But continuity remained unbroken.2

At a time of fresh starts and institutional succession, however, the UN’s founders had little incentive to point out these similarities, particularly to members of the US Senate. One of the few scholars to remark on how much the new emperor’s clothes looked like the last one’s, Leland M. Goodrich, reported that

quite clearly there was a hesitancy in many quarters to call attention to the essential continuity of the old League and new United Nations for fear of arousing latent hostilities or creating doubts which might seriously jeopardize the birth and early success of the new organization.3

So why were expec...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Context

- Part II Tools

- Part III Challenges

- Notes

- Appendix 1: Provisional rules of procedure of the Security Council

- Appendix 2: Size of UN peacekeeping forces, 1947–2005

- Bibliographical essay