eBook - ePub

Globalization, Lifelong Learning and the Learning Society

Sociological Perspectives

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book critically assesses the learning that is required and provided within a learning society and gives a detailed sociological analysis of the emerging role of lifelong learning with examples from around the globe. Divided into three clear parts the book:

- looks at the development of the knowledge economy

- provides a critique of lifelong learning and the learning society

- focuses on the changing nature of research in the learning society.

The author, well-known and highly respected in this field, examines how lifelong learning and the learning society have become social phenomena across the globe. He argues that the driving forces of globalisation are radically changing lifelong learning and shows that adult education/learning only gained mainstream status because of these global changes and as learning became more work orientated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Globalization, Lifelong Learning and the Learning Society by Peter Jarvis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Adult Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Lifelong learning in the social context

As we explained in the Preface, the first volume of this trilogy focused primarily on philosophical and psychological approaches to learning although the social context was always recognised, so that in order to explore the sociology of lifelong learning it is necessary to revisit the previous argument and locate the individual learner in the social context (see also Jarvis 1985). Consequently, the first section of this chapter returns to the theory of learning adopted in Volume 1 and explains how a sociological perspective may be used to interpret the same material. Thereafter, the chapter will look at the social processes of learning and in the third section will examine the nature of social power and the way in which it impinges upon human learning. The chapter highlights the tension between social conformity and individualism and in so doing it will look back to the brief discussion on authenticity and autonomy that occurred in Volume 1 within the framework of learning theory. It concludes with a brief discussion of how specific sociological theories presuppose certain types of learning.

Theory of lifelong learning

Following the definition of learning, referred to in the Preface, we defined lifelong learning as the combination of processes throughout a lifetime whereby the whole person – body (genetic, physical and biological) and mind (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, emotions, beliefs and senses) – experiences social situations, the perceived content of which is then transformed cognitively, emotively or practically (or through any combination) and integrated into the individual person’s biography resulting in a continually changing (or more experienced) person.

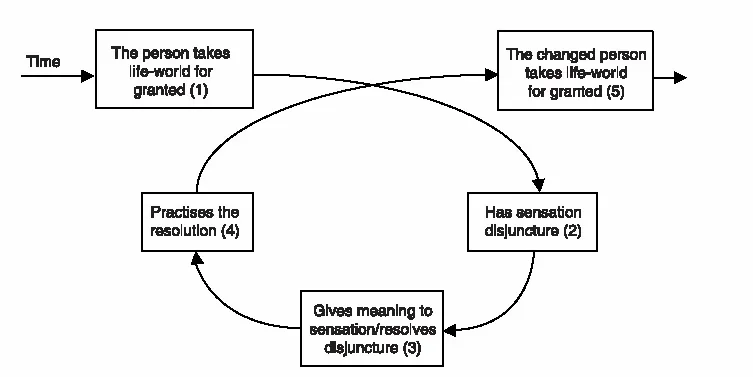

Basically, this is the same definition as that for human learning but just slightly adapted to recognise the lifelong nature of learning. Indeed, it was argued that learning is possible wherever conscious living occurs, but that there is a real possibility that learning actually occurs beyond the bounds of consciousness – I have focused on pre-conscious learning from the time that I first wrote about learning (Jarvis 1987). An omission in Volume 1 was Marx’s use of the idea of false consciousness and its relationship to learning – to which I will allude in the final chapter. However, it is important to note that we are born in relationship and that we live the whole of our lives within a social context; the only time when most of us sever all relationships is at the point of death. Consequently, no theory of learning can legitimately omit the life-world or the wider social world within which we live since learning is a process of transforming the experiences that we have and these always occur when the individual interacts with the wider society. However, experience itself begins with body sensations, e.g. sound, sight, smell, and so on. Indeed, we transform these sensations and learn to make them meaningful to ourselves and this is the first stage in human learning. We are more aware of it in childhood learning because many of the sensations are new and we have not learned their meaning, but in adulthood we have learned sounds, tastes, etc. and so we utilise the meaning as the basis for either our future learning, or for our taken-for-grantedness, in our daily living. For example, I know the meaning of a word (a sound) and so I am less aware of the sound and more aware of the meaning, and so on. I depicted this process in Figure 1.1.

Significantly, we live a great deal of our lives in situations we have learned to take for granted (box 1), that is we assume that the world as we know it does not change a great deal from one experience to another similar one (Schutz and Luckmann 1974), although such an assumption is a little more contentious in this rapidly changing world – but we will argue below that not all knowledge changes that rapidly. Over a period of time, we actually develop categories and classifications that allow this taken-for-grantedness to occur. Falzon (1998: 38) puts this neatly:

Encountering the world . . . necessarily involves a process of ordering the world in terms of our categories, organising it and classifying it, actively bringing it under control in some way. We always bring some framework to bear on the world in our dealings with it. Without this organising activity, we would be unable to make any sense of the world at all.

Figure 1.1 The transformation of sensations: initial and non-reflective learning.

But we recognise that very young children may not always be in a position to make such assumptions; they are in a more continuous state of learning from novel situations.1 Traditionally, however, adult educators have claimed that children learn differently from adults, but I am maintaining here that the processes of learning from novel situations is the same throughout the whole of life, but children have more new experiences than do adults and hence there appears to be some difference in their learning processes. In novel situations throughout life, we all have new sensations and then we cannot take the world for granted; we enter a state of disjuncture – the situation when our biography and the meaning that we give to our experience of a social situation are not in harmony – and immediately we raise questions: What do I do now? What does that mean? What is that smell? What is that sound? and so on. Now there are at least two aspects to this questioning process: I cannot give a meaning to the sensation that I have, and I do not know the meaning that those around me give it. Often they coincide and the answers that we get coincide, but it does not mean that the response to the second point necessarily answers the first! If it did, then there would be no room for disagreement, we would live in a totalitarian environment and learning would merely be a matter of remembering. The fact that they often coincide illustrates how culture is transmitted relatively from generation to generation.2

Significantly, disjuncture occurs in both of these ways, either because we cannot give meaning or because we do not know the meaning that others around us give. It can also occur in any aspect of our person – knowledge, skills, sense, emotions, beliefs, and so on. It can occur as:

- a slight gap between our biography and our perception of the situation to which we can respond by slight adjustments in our daily living which we hardly notice since it occurs within the flow of time;

- a larger gap that demands considerable learning;

- in a meeting between persons for it takes time for the stranger to be received and a relationship, or harmony, to be established;

- wonder at the beauty of the cosmos, pleasure and so forth at that experience. In some of these situations, it is impossible to incorporate our learning from them into our biography and our taken-for-granted. These are what we might call ‘magic moments’ for which we look forward and hope to repeat in some way or other.

Naturally disjuncture can occur in different dimensions of the whole person simultaneously or separately. Disjuncture, then, is a varied and complex experience but it is from within the disjunctural that we have experiences which start our learning processes. There is a sense in which learning occurs whenever harmony between our biography (past experiences) and our experience of the ‘now’ needs to be established, or re-established. Many of these disjunctural situations may not be articulated in the form of a question but there is a sense of unknowing or unease (box 2). However, unknowing is also a social phenomenon since one person’s knowledge is another’s ignorance, and so on. Through a variety of ways we give meaning to the sensation and our disjuncture is resolved. An answer (not necessarily a correct one, even if there is one) to our questions may be given by a significant other in childhood, by a teacher, incidentally in the course of everyday living, or through self-directed learning, and so on (box 3). The answers are social constructs and so we begin to internalise the social world through learning. Once we have acquired an answer to our implied question, however, we have to practise it in order to commit it to memory (box 4). The more opportunities we have to practise the answer to our initial question the better we will retain it in our memory.3 Since we do this in our social world we get feedback, which confirms that we have got a socially acceptable resolution or else we have to start the process again, or be different. A socially acceptable answer may be called correct, but we have to be aware of the problem of language – conformity is not always ‘correctness’ and our whole understanding is social. Here we see ‘trial and error’ learning as we seek to learn the socially accepted answer. In addition, we have to recognise that those in power can define what is regarded as socially acceptable and we are only in a position to reject this answer the more confident we are of our own position. As we become more familiar with our socially acceptable resolution and memorise it we are in a position to take our world for granted again (box 5), provided that the social world has not changed in some way or other. Most importantly, however, as we change and others change as they learn, the social world is always changing and so our taken-for-grantedness in box 5 is always of a slightly different situation. The same water does not flow under the same bridge twice and so even our taken-for-grantedness is relative.

The significance of this process is that once we have given meaning to the sensation and committed a meaning to our memories then the significance of the sensation itself recedes in future experiences as the socially acceptable answer (meaning) dominates the process, and when disjuncture then occurs it is because we cannot understand the meaning, we do not know the meaning of the word, and so on. It is in learning it that we incorporate culture into ourselves; this we do in most, if not all, of our learning experiences. In this sense, we carry social meaning within ourselves – whatever social reality is it is incorporated in us through our learning from the time of our birth. Indeed, this also reflects the thinking of Bourdieu (1992: 127) when he describes habitus as a ‘social made body’ and he goes on in the same page to suggest that: ‘Social reality exists, so to speak, twice, in things and in minds, in fields and in habitus, outside and inside of agents.’ This is something that Epictetus first realised two thousand years ago (see Arendt, Book 2, 1977: 78) when he regarded the internal image as something ‘deprived of its reality’. There is a sense, however, in which we might, unknowingly, be imprisoned behind the bars of our own minds,4 although it could be argued that by an exercise of will we can break out of this, provided we know that we are imprisoned!

However, culture is not a monolithic phenomenon, and so we are exposed to a number of different interpretations of ‘reality’ in the great majority of circumstances, although there have been societies, especially primitive ones, in which only one interpretation is understood or accepted: these are totalitarian societies – or organisations – and they always seek to reproduce themselves – we will return to this later in the book.

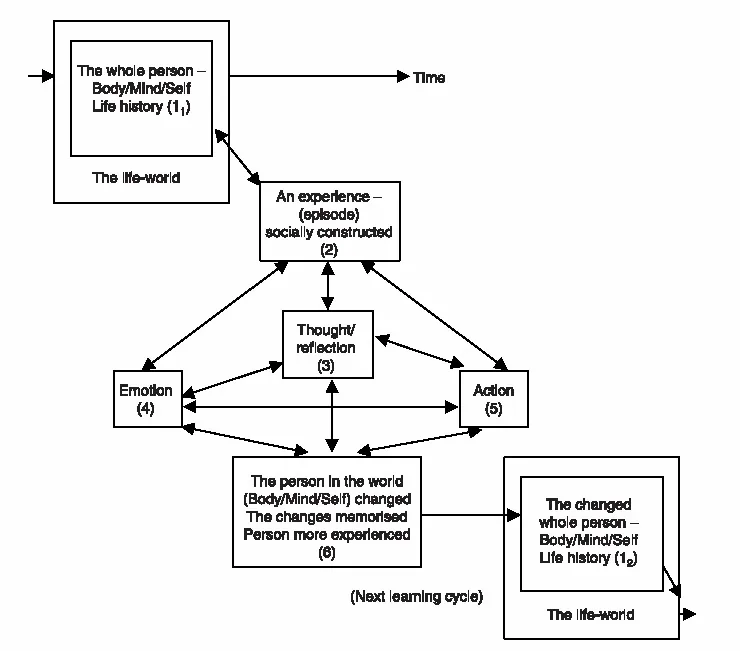

Human learning, then, is more than just transforming the bodily sensations into meaning; it is the process of transforming the whole of our experience through thought, action and emotion and thereby transforming ourselves as we continue to build perceptions of external reality into our biography. I depicted this process in Figure 1.2. In this diagram I have tried to capture the continuous nature of learning by pointing to the second cycle. However, this diagram must always be understood in relation to Figure 1.1, since it is only by combining them that we can begin to understand anything of the complexity of human learning.5 Box 1 has become a much more significant part of this attempt to understand human learning than even it was in the first volume of this trilogy. People are located in their life-worlds and in contemporary society the life-world changes so rapidly that Bauman (2003, 2005a) has typified it as liquid – that is it is never static, always changing. (We will explore the reasons for this rapid change in later chapters). Consequently, the rapidly changing life-world is frequently inducing a state of disjuncture, often just a slight one to which we adjust but sometimes it is a greater one which requires considerable learning. This rapidly changing world has, therefore, produced a situation where individuals are compelled to learn all the time in order to find their place in society. Lifelong learning is now endemic! Bauman (2005a: 1) opens his book Liquid Life in the following manner: ‘Conditions of action and strategies designed to respond to them age quickly and become obsolete before the actors have a chance to learn them properly.’

Consequently, we live in a state where we are conscious of change all the time and this means that, unless we disengage from social living, we are constantly having potential learning experiences. Having had an experience (box 2), which occurs as a result of disjuncture, we can reject it, think about it, respond to it emotionally or do something about it – or any combination of the three (boxes 3–5). As a result we become changed persons (box 6) but, as we see, learning is itself a complex process. Once the person is changed, it is self-evident that the next social situation into which the individual enters is changed – not only changed because the person has changed but changed because the other has also been undergoing learning experiences and has been changed as a result. We can conclude, therefore, that learning involves three transformations: the sensation, the person and then the social situation.

Figure 1.2 The transformation of the person through learning.

However, as life progresses the developing individuals become more stable and less likely to change radically in certain circumstances. In other words, individuals gain a sense of self and self-identity and they can become actors in the situation as well as recipients. Consequently, a tension might then develop between the social interpretations given to a certain situation and those given by individuals themselves; people are not necessarily so malleable as to mirror the social situation perfectly although, as a result of our early socialisation, we do reflect a great deal of our primary culture and are, in certain ways, emotionally committed to it. We can see, therefore, that there is a potential tension between ourselves, as individuals, and the social situation within which we live; when we can take the social reality for granted, it shows that we ‘fit in’ – that is, we conform. But when we feel a sense of unease, it may be because we are in a disjunctural situation or else we have no desire to conform to the expectations placed upon us. Both of these situations are potential learning situations. Feeling unease, or awkwardness, may be embarrassing because it suggests a sense of ignorance, but it may also be a matter of conscience6 – we feel that we have to stand out for what we believe. Paradoxically, we can experience conscience problems when we conform because we have caved in to external pressures, or when we fail to do so because we have stood out for our beliefs, depending on our beliefs and values. Being true to ourselves or our values and beliefs demands confidence and courage amongst other things and so we are not always conformists and learning is sometimes innovative and creative – it is also self-initiated on occasions.

From this initial analysis, we can see that issues of autonomy and authenticity are raised from the outset of any theory of human learning in the social context. For instance, we may feel that when we choose to act in a certain way as a result of an experience or when social pressures are put on us to act in this manner, we are still free to act in another way even if we do not so. We might claim that while we chose to conform to the demands of a given situation, we knew that it was possible to act in another way and that we were capable of doing so. Consequently, we feel free to be autonomous individuals – but the extent to which we are is another question.

Nevertheless, we might feel that we have to be true to ourselves, and therefore we have to reject the demands of a given experience in order to be the selves that we have learned to be. Indeed, Nietzsche (Cooper 1983) has argued that to accept passively what we are told is to be inauthentic, whereas to be authentic we have to be true to ourselves at whatever cost, even if it means non-conformity. It also means that we do not accept passively what Nietzsche has taught us! In both of these situations, we can see the issue of power and we will return to this in the final section of this chapter, but before we do so, it is necessary to examine ways in which we learn to be social individuals and this constitutes the next section.

The social processes of learning

The process that we have described here might be depicted by Figure 1.3. In this diagram, the arc represents the all-encompassing culture into which we are born.7 In primitive society it was possible to describe this as a single culture, but now this all-encompassing culture is what might also be described as multi-cultural. Culture is a problematic concept and merely by describing it as all-encompassing does not obviate the problem since it is not even the same phenomenon for all people in the same area – young people still grow up in the UK, for instance, with their ethnic cultures, even though they also acquire a sense of ‘Britishness’ and others a sense of being a Muslim, and so on. We all have our own life-worlds. Culture is also a difficult term to define, since it has many accepted meanings. Even so, at the risk of simplifying the concept, we will define it as the totality of knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes and norms and mores of a social grouping, so that we can see that ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures and tables

- The author

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Lifelong learning in the social context

- Chapter 2: Human learning within a structural context

- Chapter 3: Human learning within a global context

- Chapter 4: Outcomes of the globalisation process

- Chapter 5: The information and the knowledge society

- Chapter 6: The learning society

- Chapter 7: Lifelong learning

- Chapter 8: Life-wide learning

- Chapter 9: Participants in lifelong learning: Teachers and students

- Chapter 10: The changing nature of research

- Chapter 11: Policies, practices and functions

- Chapter 12: The need for the learning society and lifelong learning

- Appendix: Infinite dreams, infinite growth, infinite learning – the challenges of globalisation in a finite world

- Notes

- References