- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book assesses the value of flagship developments and draws out lessons for best policy and practice. It looks at marketing strategies and the sales process for flagship developments and the areas in which they are located for urban regeneration. It discusses the management of marketing strategies and the development through the policy formulation, project implementation and policy/project evaluation. The author examines the strategies to date of 'marketing the city' and the conceptual scope and limits for developing the concept. He also looks at the extent to which people can be integrated into the urban 'product' and the advantages and disadvantages of this. Finally the impact of all these issues is assessed for the policy makers, planners, developers, architects and city authorities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marketing the City by H. Smyth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & Landscaping1

City visions and flagship developments

1.1

VISIONS FOR THE CITY

VISIONS FOR THE CITY

Change is inherent to our society. The scale and rate of change accelerated throughout the 1980s and by the turn of the decade it was more than apparent that many of these changes were to be of lasting significance. The demise of the Eastern Bloc was the most dramatic series of events. The process and the promise of further upheaval will continue. As the dominant culture of the West moves towards the millennium, the psychology of the next years will mould expectations about what is to come and the visions people would wish to see.

What sort of cities do we wish to see in the next century? How do we get from here to there? Harnessing our experiences of the recent past in order to shape the processes that will mould and reform our urban environment is central to achieving our expectations. Renewing the existing fabric and regenerating the areas of decline and dereliction is one of the greatest challenges for the well-being of society. This challenge embraces not only the physical form but those affected by the degeneration. Yet this raises two vital questions. The first concerns the extent of the gap between our visions for our cities and the constraints of achieving these in the changing social, political and economic circumstances of the next few years. The second question must address what the nature of our vision is for future cities, and we must immediately recognize that our visions do, and will, vary considerably. Our visions tend to be formed from an amalgam of ideas. These ideas emanate from current interests and concerns, such as:

• an attractive, safe and healthy environment;

• a city without homelessness;

• a city in which citizens and organizations contribute rather than take out;

• adequate housing and income for everybody;

• opportunities to pursue business interests, development or other activities;

• good communications and infrastructure;

• a place of cultural excellence.

Each of these ideas has implications for implementation. From where will these ideas be resourced? Who will decide upon and implement the initiatives and projects required to realize the visions? Some of the ideas are in conflict with each other and will either be excluded through the policy process or lose out in competition for resources in the market-place.

Certainly there has been no clear vision of the future for our urban environment since the 1960s. Perhaps the vision was not always entirely clear, but there was a shared sense of a goal, a ‘rational’ end, which was being negotiated and fought over constantly in the efforts to determine the future. Yet a renewed sense of vision, an overall ‘urban project’ is needed for future development to be purposeful (Harvey, 1989a), whether from a partisan viewpoint or for broader social and economic well-being. For a vision to emerge that is implementable, it must be shared in the broadest terms by key constituents of society—local people, a selection of interest groups, politicians, developers and business. A vision requires more than just acceptance, the lowest common denominator of legitimacy; it needs active support and a high degree of involvement.

1.2

MARKETING THE CITY

MARKETING THE CITY

Having such a vision is a long way off, yet its formation has already started. Its formation has been arising out of the most innovative element of recent urban development, that is, the process of marketing the city. Developing a coherent marketing strategy for any city is still remote and, indeed, there may be some serious restraints on achieving such a goal conceptually and through the implementation stages in a meaningful way. The purpose of marketing a city is to create strategies to promote an area or the entire city for certain activities and in some cases to ‘sell’ parts of the city for living, consuming and productive activities.

Successful developments start with a market strategy for that development, yet their promotion frequently demands a market context beyond the boundary of the site, or indeed of the area. The city strategy is the next logical step, which in turn begins to raise issues about competing interests as to what sort of city we need, what sort of urban regeneration and development is needed. In other words, the process of marketing the city begs the question as to what sort of cities we wish to see. What concepts, ideas, assumptions and processes are being brought together in marketing strategies? Assuming these can be implemented, how are these strategies going to shape our cities, and do they form part of a vision in which we wish to share? The negotiation process has already started in practice with concepts being tentatively tested, the results of which will filter through our thinking and practice into the next century.

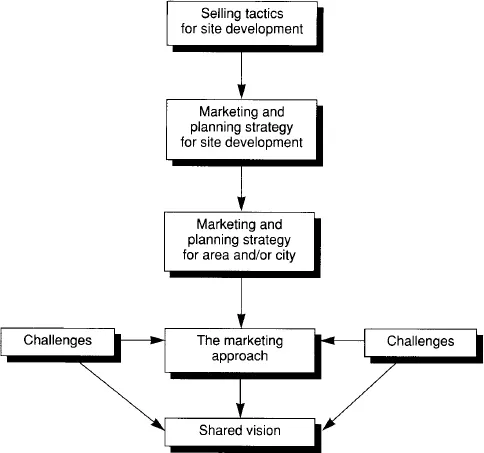

A few qualifications will demonstrate the significance of these negotiations. Firstly, marketing is a process, because the application of marketing concepts to the city is both recent and immature. Many concepts are not easily transferable from products and services, and, in addition, their appropriateness is still being evaluated by advocates. Marketing the city is therefore still at an experimental stage and the process has unfolded in a gradual and frequently ad hoc way. Secondly, although a shared vision may involve a marketing approach, it must contain different strategies for different cities because each is unique. A shared vision may exclude marketing or include a few elements, for the vision may arise from elsewhere, perhaps as a challenge to a marketing approach. Other influences are being debated (cf. Coleman, 1990; Harvey, 1989a; Healey, 1992; Rogers and Fisher, 1991; Wilson, 1991); however, what is happening ‘on the ground’ is influencing the envisioning process, as shown in Figure 1.1.

It is a process in its early and formative stages without a clear end in sight. The form it will take will be influenced by the events of the next years and may fail to emerge. At this stage it is impossible to make a prediction, yet the process has begun.

1.3

MARKETING AND FLAGSHIP DEVELOPMENTS

MARKETING AND FLAGSHIP DEVELOPMENTS

This book is contributing to the envisioning process because it seeks to evaluate the phenomenon of the last decade that has done much to assert marketing as a city concept, that is, the flagship development.

In some respects, flagship developments have already lost part of their policy appeal and the recession has served to undermine many of the underpinning economic assumptions. New policy approaches are being tried and tested, yet these have been born out of the experience of flagship developments and hence are part of the process and debate. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on issues raised by flagship developments, for it is from projects like these that our grand visions and future policies will flow.

The purpose of this research is to evaluate those projects that have come to be known as flagship developments. The subject appears to be a definable area, yet the very purpose of a flagship is to ‘mark out ‘change’ for a city’ (Bianchini, Dawson and Evans, 1990, p.11; see also Bianchini, Dawson and Evans, 1992). The change envisaged extends beyond the physical boundaries of the flagship and contributes to the development and the economic and policy base of the area and city. Immediately the sphere of research grows, raising larger development issues both for implementing flagship projects and for future policies that will shape the urban form beyond the millennium. The sphere of research grows because the flagship is part of the ‘selling’ of an area and marketing the city. It is from both the projects themselves and the broader implications that we can learn important lessons for future policy and development.

Figure 1.1 Marketing and negotiating a city vision

1.4

DEFINITION

DEFINITION

Firstly, it is necessary to define a flagship development. They have been cited as being significant, high profile developments that play an influential and catalytic role in urban regeneration, which can be justified if they attract other investment (Bianchini, Dawson and Evans, 1990, 1992). A more detailed categorization will be provided at a later stage, it being sufficient to state at this point that a flagship comprises the following elements:

• a development in its own right, which may or may not be self-sustaining;

• a marshalling point for further investment;

• a marketing tool for an area or city.

The general thrust is not entirely new. There is a long history of local public and private sector developments, which were intended to have a broader remit than the immediate function for the development. There are new ‘twists’ in the particular concept of the flagship. Their role within urban regeneration during the 1980s has been of enormous significance, arising from the proactive development of flagships, the post hoc labelling of projects and also the reduction of overall central government spending on urban regeneration within central city areas.1 Their most prominent role, however, has been in the tentative exploration and development of marketing concepts for a project and, indeed, for a city.

1.5

ORIGINS

ORIGINS

The specific concept of the flagship development originates from the United States, Baltimore providing the inspiration for many projects and a role model for some. Baltimore had been experiencing long-term decline and its poor image was a product of divestment, deprivation and the social unrest of the 1960s. In 1970 a city fair was held, which successfully united a number of disparate neighbourhoods and interest groups. Within two years the fair was attracting nearly two million visitors. Civic pride was being restored. The recession, commencing in 1973, ushered in a further wave of redundancies. It was decided to institutionalize and further commercialize the fair. The construction of the Maryland Science Center, the National Arena, Convention Center, a marina, hotels, and a variety of leisure and retail facilities was the result. Baltimore reached the coveted front cover of Time magazine as the ‘renaissance city’, the Inner Harbor area became an international tourist destination and the flagship project was born (Harvey, 1991).

The onset of the 1990s was not painting such a rosy picture for Baltimore. Many of the poorest neighbourhoods had been largely shut off from the new growth, the trickle-down effect through the economy being limited. The recession in general was affecting both retailing and tourism and there was a vast oversupply of commercial property development. The proposition was mooted that the whole development thrust had exacerbated conditions in the poor neighbourhoods by diverting resources away from housing into an overheated property market (Harvey, 1989a).

1.6

HYPOTHESIS

HYPOTHESIS

There is a long tradition of Britain emulating the United States, and the development of flagships is no exception. The question this raises is whether Britain has adopted the better practices and learnt from being followers rather than pioneers. Indeed, have flagship development initiators thought through the implications of their projects in a thorough way in the short and long term? Or have projects been conceived as a reaction to circumstances, as a ‘good idea’? Have they been implemented with energy and enthusiasm, but without the structures and support necessary for successful implementation and continuing management? There is a hypothesis to be tested:

Is it not the case that flagship developments are an expensive means to effectively promote urban regeneration, that is, economic growth and social well-being, within an area?

This hypothesis appears at first sight to tie down the subject. Yet on further consideration it becomes more difficult. Embedded within the question is the need to address the broader role of urban policy. A supplementary question illustrates this: is a flagship development a fundamental tool for unlocking latent demand within a local economy? If it is, then its significance is very broad and, I would suggest, has not therefore been fully taken on board in Britain, even—or especially—within recessive conditions. If it categorically is not, then are we simply looking at a ‘sign’? Such an effort to create some sign of life in a local economy may prove very expensive. Or perhaps we should treat it culturally as a legitimate ‘experience’ in terms of both the activities that the flagship accommodates and as a visual contribution to urban regeneration. As such it becomes part of a process, which is an end in itself, because achieving a steady-state goal is impossible. The minute a goal is achieved it becomes the subject of change in a dynamic economy.

1.7

CULTURAL CONTEXT

CULTURAL CONTEXT

The cultural context places flagships in the arena of ‘postmodern culture’. Flagships can be seen as both an important expression of that culture, even more so when the planning and architecture is postmodern, and an important contributor to that ferment. In an urban context this is experiential, Jonathan Raban’s Soft City (quoted in BBC, 1992; Harvey, 1989a) being used as a benchmark for the perception of the period as postmodern:

Cities, unlike villages and small towns, are plastic by nature. We would mould them in our images: they, in their turn, shape us by the resistance they offer when we try to impose our own personal form on them. In this sense, it seems to me that living in a city is an art, and we need the vocabulary of art, of style, to describe the peculiar relation between man and material that exists in the continual creative play of urban living. The city as we imagine it, the soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate in maps and statistics, in monographs on urban sociology and demography and architecture. (Raban, p. 9–10)

The implications tend to polarize our thinking. At one pole, our thinking moves in the realm of pure imagination or grand visions, the implementation being incidental; at this pole the ‘good idea’ cannot be evaluated unless implemented and the implementation contributes to the wider goals of the ‘vision’. Or, at the other pole, our thinking becomes concerned merely with the immediate experience of the completed project, rendering both the private aims or public policies ephemeral and the investment short-lived in functional and physical terms. This may imply, as Daniel Bell (1978) proposed, that the organization of space has ‘become the primary aesthetic problem of mid-twentieth century culture’ (quoted in Harvey, 1989a, p.78). Maintaining the aesthetic momentum has tremendous cost implications, especially when harnessed with fashion, as well as posing problems for long-term economic stability. Here we are looking at the possible content of a marketing strategy for the city, whether by design or by default. Perhaps the experience described by Raban means that the environment is no more than packaging for the soft city of experience. Perhaps it is a separate ‘product’ in its own right and one that can help organize our lives more efficiently. This again raises the question posed of Baltimore: are the benefits real, lasting? If there are no lasting benefits and no identifiable economic opportunity costs, then we are left with the proposition of Bourdieu (1984): ‘the most successful ideological effects are those which have no words’ (quoted in Harvey, 1989a, p.78). The function of a flagship is reduced to inducing social stability, assuming the generated experience is sustainable for enough people over a long period and is targeted towards those who are potentially the harbingers of disruption. Perhaps the analysis should take a step back: what are the markets and what is the purpose of marketing the city?

While each of the issues raised is interesting and needs to be addressed, in themselves they are part of a melting pot of ideas. Understanding the development options, the needs to be met and evaluating the promotion efforts is just beginning, for many of the concepts behind flags...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Black and white plates

- 1 City visions and flagship developments

- 2 Context for urban policy and marketing the city

- 3 Research approach

- 4 Marketing framework

- 5 Project management

- 6 Project impact

- 7 Case studies

- 8 The Watershed Complex

- 9 The International Convention Centre

- 10 The Hyatt Regency Hotel

- 11 Brindley Place and the National Indoor Arena

- 12 Theatre Village

- 13 Byker Wall

- 14 Implications of flagships for urban regeneration and marketing

- 15 Future development and city visions

- Notes

- References

- Author index

- Subject index