- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book opens the series with a consideration of the social construction of social difference. Taking the body as the point of departure, it deals with the processes through which social problems and social inequalities are constructed. In particular, it examines the shifting ways in which our ideas about issues such as 'disability', 'race' and ethnicity, and sexuality influence the development of social policies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Embodying the Social by Esther Saraga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Health Care DeliveryCHAPTER 1

The Social Construction of Social Problems

by John Clarke and Allan Cochrane

1

Introduction

In this chapter we explore the question of what it is that makes social problems social. What is it that makes some issues and not others worthy of public attention, anxiety or action? The emphasis in this chapter is placed on examining the processes by which social problems are socially constructed. We will be concerned with the ways in which problems are identified, defined, given meaning and acted upon. In the course of examining these processes, we will be giving particular attention to the significance of conflicts about how social problems are defined, interpreted and responded to. These issues about the social construction of social problems form the central concerns of this chapter and provide the basis for exploring a number of approaches in the social sciences that address these processes of defining, interpreting and giving meaning to social problems.

2

What is ‘social’ about a social problem?

In the late twentieth century a list of current social problems in the UK might include poverty, homelessness, child abuse, disaffected young people and non-attendance at school, school discipline, the treatment of vulnerable people in institutional care, vandalism, road rage, lone parenting and divorce. This brief list was drawn up from news items on television and radio and in newspapers in the month that this chapter was being written. As you read this chapter, some of these may still be issues, some may have disappeared, while new problems may have attracted attention. It is not obvious what they have in common, except that they are the subject of current concern. That fact—the capturing of public interest, anxiety or concern—is probably the best place to start this discussion, since it suggests that one answer to what is ‘social’ about a social problem is that such problems have gained a hold on the attention of a particular society at a particular time.

There is a point in stressing the word ‘particular’ here. Other societies may be preoccupied by other problems: what commands public attention in Germany, the USA or China is likely to be different in at least some respects to what is a current social problem in the UK. It is also true that if we looked back at earlier historical periods, only some of the list of current social problems would be visible then. In the late nineteenth century, for example, we would find that poverty, the maltreatment of children and divorce were being discussed as social problems, but others on the list did not attract much attention. There are two possible explanations for such differences. One is that social problems change. If in the late nineteenth century there were no homeless people, then we would not expect homelessness to have been discussed as a social problem. The second reason is that what is perceived as a social problem may change. Thus there may indeed have been people who were homeless in the late nineteenth century, but their situation was perceived not as a social problem, but rather as a ‘fact of life’ or as the consequence of mere individual misfortune— neither of which would make it a social problem.

Writing in the 1950s, the American sociologist C.Wright Mills (1959, pp. 7– 10) drew a distinction between ‘personal troubles’ and ‘public issues’. He suggested that although there were many ‘troubles’ or ‘problems’ that individuals experienced in their lives, not all of these emerged as ‘public issues’ which commanded public interest and attention or which were seen as requiring public responses (‘what can we do about X?’). Mills’s use of the term ‘personal’ may be slightly misleading, since it implies that it is the difference between individual and collective experience that matters. For us, however, the important distinction is between issues that are ‘private’ (that is, to be handled within households, families or even communities) and those which are ‘public’ (that is, to be handled through forms of social intervention or regulation). One factor that may make a difference to whether things are perceived as private troubles or public issues is scale or volume. If only a few people experience some form of trouble, then it is likely to remain a private matter and not attract public concern. If, however, large numbers of people begin to experience this same trouble—or fear they might—it may become a public issue. The process can probably best be explored with the help of an example.

2.1

From private trouble to public issue: the emergence of negative equity

In the housing market, owner-occupiers have occasionally sold their property at a price below that which they paid for it. In the early 1990s, large numbers of property owners in the UK (and particularly in southeast England) found that the market value of their houses and flats had fallen below the original purchase price. A private trouble emerged as a public issue. It was named, and became the problem of ‘negative equity’. This was identified as a widespread problem rather than a matter of individual misfortune: it was seen to have causes (in the state of the economy) which lay beyond the reach of the individual. It was also identified as something that required a public response—from mortgage lenders and the government.

Can this shift of a private trouble to a public issue be understood as a consequence of the numbers of people involved?

The numbers involved provide only part of the explanation why this trouble became a public issue. Other ‘troubles’ involving equally large numbers of people attracted less attention and concern. For example, the continuing rise in rents for tenants of council housing and housing associations, which took place at the same time, was largely viewed as a fact of life. Furthermore, despite the attempts of housing professionals to place the issue on the public agenda, the decaying state of Britain’s owner-occupied housing stock (built before 1945) continued to be defined as a personal problem facing those who happened to be living in older houses. They were expected to resolve it through their own investment in renewal and repair, rather than through any collective effort. We might suggest that a number of other features of negative equity helped it become a public issue:

- Who was involved? The social and political standing of those experiencing this trouble affected its visibility. Home owners were seen as innocent victims of a situation beyond their control. They were the symbolic representations of government policies designed to create a ‘property-owning democracy’. Negative equity was thus a politically sensitive matter.

- What was its claim on public attention? Negative equity was seen as connected to matters of public policy—first, the drive to extend home ownership and, second, the contemporary management of the national economy which was associated with an initial boom and then a slump in housing prices.

- What sort of problem was it? Negative equity was seen as having significant social and economic consequences. It was associated with mounting personal debt, a lack of social mobility, and a fear of the future that prevented people taking risks. In particular, it was seen as causing a problem of consumer confidence: this reduced patterns of consumer spending, which in turn further threatened the prospects of economic growth. It was therefore also a political problem for the government, as it provoked extensive public discussion about the presence or absence of a ‘feel-good factor’, particularly among the government’s erstwhile supporters.

What this brief example suggests is that the scale of a ‘trouble’ is not by itself a sufficient condition for understanding why the trouble becomes a public issue. We need to understand the social context in which it occurs—its links to other current issues and values. The case of negative equity also suggests that we need to think about who is involved and how they are perceived, in terms of their social standing and significance. In very simple terms, we might suggest that there are two routes to troubles becoming public issues which are distinguished by the question: whose problem is this?

Some troubles become social or public problems as a result of the actions of those people who experience them (or those who speak on behalf of such people). Thus, campaigns aim to capture public attention and direct it to the conditions or experiences that specific groups of people are suffering. Negative equity would be one example of this route. Other examples include campaigns to draw attention to the widespread incidence of domestic violence, despite its relative public invisibility; to raise concern about the abuse or maltreatment of vulnerable people in institutional care; or to reveal the scale of, and suffering associated with, homelessness. Such campaigns try to articulate the experience of a particular condition and demand public action to remedy it. This route is built around the argument that people have problems.

The second route is different, in that it is built around the argument that some people are problems. There are some types of people who are seen as a problem for others or for society at large (even if these people do not define themselves in the same way). For example, we might be able to identify groups of people who are seen to pose a threat or danger to society in some way: vandals, noisy neighbours, hooligans, prostitutes, the mentally ill, and so on. The demand here is that society does something about ‘these people’—police them, lock them up, treat them, and so forth.

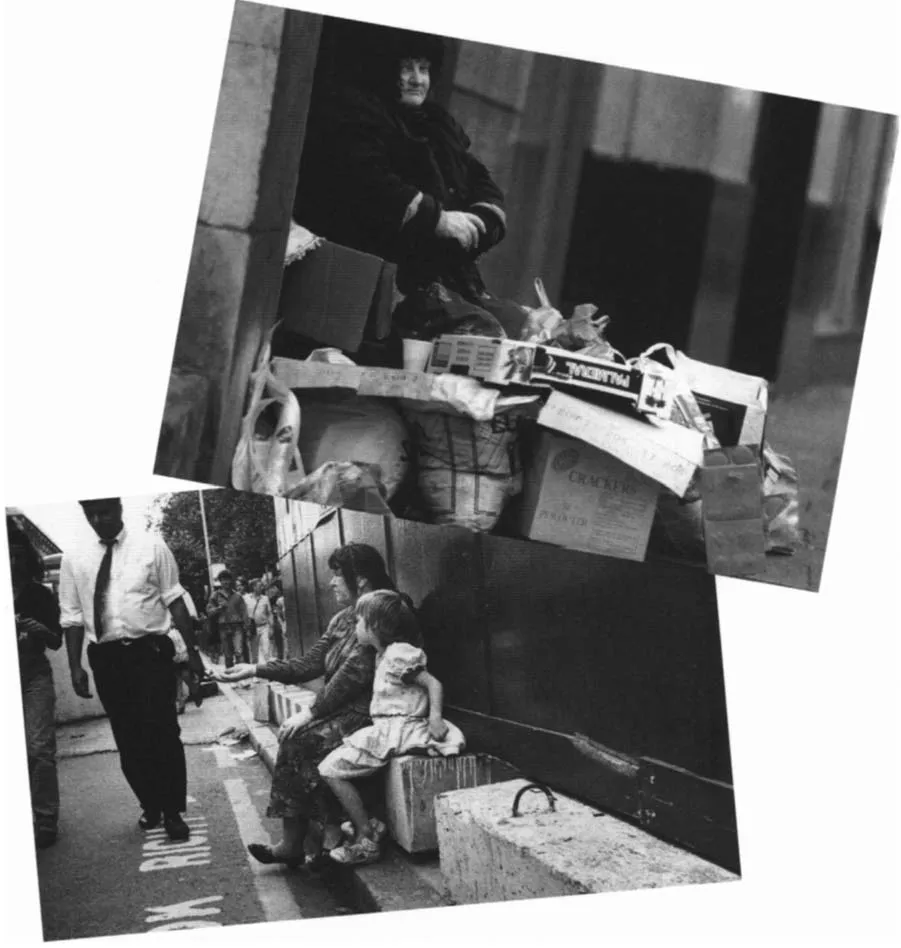

Sometimes, of course, the same problem might be identified through both these routes. If we examine homelessness as a social problem, it is possible to see its being defined as a problem that some people have and as a problem that some people are. In the first case, the problem is perceived as the lack of access to a basic human need—adequate accommodation—which results in homeless people experiencing deprivation, misery and suffering. The appeal is to a sense social justiceof social justice. In the second case, the problem of homelessness is perceived as a threat to everyday life: homeless people clutter city streets, are a health risk, prevent ‘normal’ people going about their daily business, and are associated with crime and other perceived threats to the rest of society. The appeal is to a sense of social order. Both routes acknowledge the importance of social differentiation, but they do so in different ways. The first implies that steps need to be taken to reverse or compensate for the inequalities or unfairness that arises from particular social arrangements, while the second implies that those who do not conform to accepted and widely understood norms—or standards—of behaviour need to be taught or helped to do so.

social order

ACTIVITY 1.1

Can you think of other social problems where both these routes are visible?

Homelessness: a shortage of adequate accommodation, or a threat to society?

Use the grid below to help you to do this. We have taken one example, ‘the mentally ill’, and have filled in the first column to show you how you might answer. Try to fill in the second column, and then see if you can add two further examples.

Social problem People have problems People are problems

Mental illness

Mentally ill people are ill through no fault of their own and require/deserve treatment.

Mental illness can affect all of us (and even if we have not all suffered from it in some form, most of us will know someone who has).

As far as possible mentally ill people should be re-integrated into their communities, since excluding them from ordinary life is likely to make their condition worse.

2.2

Social problems and social policy

Whether social problems emerge as issues of social justice or social order, they are usually associated with the idea that ‘something must be done’. Social problems represent conditions that should not be allowed to continue because they are perceived to be problems for society, requiring society to react to them and find remedies. Where private troubles are matters for the individuals involved to resolve, public issues or social problems demand a public response. The range of possible public responses is, of course, very wide. At one extreme we might point to interventions that are intended to suppress or control social problems: locking people up, inflicting physical punishments or deprivations on them, even—in the most severe form—killing them. Such interventions are intended to stop social problems by means of controlling the people who are seen as problems (juvenile delinquents, drug takers, thieves, terrorists). Those who seek the suppression and control of social problems are usually, but not always, associated with the view that social problems are a challenge or threat to social order. The point about ‘not always’ is important, since sometimes these types of intervention are presented not in terms of protecting society or social order, but as being in ‘the best interests’ of the person being punished or ‘treated’: they need a ‘bit of discipline’, they respect ‘toughness’, and so on.

However, other interventions are intended to remedy or improve the circumstances or social conditions that cause problems—bringing about greater social justice, enhancing social welfare, or providing a degree of social protection. Thus, the development of welfare states in most advanced industrial societies during the twentieth century was associated with attempts to remedy social problems or to provide citizens with some collective protection from dangers to their economic and social well-being. In the process, a whole range of issues moved from being private troubles to becoming matters of public concern and intervention. Between the late nineteenth and the mid twentieth centuries, these societies redefined the distinction between private and public matters. Sending children to school became a matter of public compulsion rather than the private parental choice that it had been until the middle of the nineteenth century. Health became a focus of public finance, provision and intervention rather than being left to private arrangements. For most of the nineteenth century unemployment was seen as something that people chose (by refusing to take work), while for most of the twentieth century it has been seen as something against which collective action and defence by the state was necessary. Unemployment was not a social problem in the UK for most of the nineteenth century, although the unemployed themselves were certainly seen as a threat to social order (being beggars, thieves and a bad example to other workers).

In the process, citizens in advanced industrial societies came to associate social problems with social interventions—often involving action by the state—that were intended to reform or ameliorate the conditions that created problems. Social welfare, and the welfare state in particular, was intimately linked to social problems. The attempts to remedy social problems—combating illness, poverty or homelessness— drove the growth of the welfare state during the twentieth century. But the questions of whether these issues really are social problems and whether state welfare is the best remedy have reappeared towards the end of the twentieth century (see, for example, Lewis and Hughes, 1998). There are now echoes of the nineteenthcentury arguments that many social problems are ‘really’ private t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Social Construction of Social Problems

- Chapter 2 A Suitable Case for Treatment? Constructions of Disability

- Chapter 3 Welfare and the Social Construction of ‘Race’

- Chapter 4 Abnormal, Unnatural and Immoral? The Social Construction of Sexualities

- Chapter 5 Review

- Acknowledgements