eBook - ePub

Walter Benjamin, Religion and Aesthetics

Rethinking Religion through the Arts

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Walter Benjamin, Religion, and Aesthetics is an innovative and creative attempt to unsettle and reconceive the key concepts of religious studies through a reading with, and against, Walter Benjamin. Constructing what he calls an "allegorical aesthetics," Plate sifts through Benjamin's writings showing how his concepts of art, allegory, and experience undo traditionally stabilizing religious concepts such as myth, symbol, memory, narrative, creation, and redemption.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Walter Benjamin, Religion and Aesthetics by S. Brent Plate in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Atheism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Atheism1

Aesthetics (I):

From the Body to the Mind and Back

About the time Benjamin was working on his postgraduate studies, developing his aesthetic theories, the Dadaists were in full swing, smashing the sacred status of the object of art. Although many of the Dada artists channeled their enraged energies against the institution of art itself, working betwixt and between contemporary art theories and larger social myths and ideologies, the German Hannah Höch (1889—1978) stands out among them—a woman in a still patriarchal art world, wrestling with gender specificities in an age of mechanical reproduction. In her photomontages Höch displays the body, chiefly the female body, within miniature tableaus that are allegories of society, drawing attention to the male gaze (long before it became de rigueur in theory) and, as with Kafka, to the alienated nature of human life in the modern industrial world. Though Benjamin never refers to Höch, she was working in Berlin at the same time as Benjamin, and her creative modes introduce us to Benjaminian aesthetics, and thus she is worth a brief discussion in this regard.1

Utilizing strategies of appropriation and juxtaposition, Höch employs visual fragments culled from photographic reproductions of art, ethnographic artifacts, and popular culture images (newspapers and magazines), mixing and merging them in new forms and thereby creating new meanings. She thus lends credence to avant-gardist Maya Deren’s claim: “All invention and creation consists primarily of a new relationship between known parts.”2 By mixing high and mass art, conflating diverse cultures and epochs, and amalgamating everyday life and sociopolitical ideologies, Höch ushers in a style of aesthetic creation that dispenses with the image of the solitary genius forming art “out of nothing.” In its stead she offers the historically motivated understanding that we cannot, in fact, break free from the past but must rather constantly deal with the images and fragments of previous conditions, environments, and situations. Viewing her aesthetic strategies through a Benjaminian lens, we see that the past is not a unified entity to be seen as an intact whole or a well-written narrative; for to see the past within the present, it is necessary to fragment it and have it offer itself up as isolated images, which can be perpetually rearranged and resituated within the present. Only in this way is history, in Benjamin’s view, able to be reactualized in the present, and only in this way does it refrain from the overwhelming ideology of myth. By fragmenting images of various worlds, Höch puts together a new image, a pieced-together creation in which the lines of juxtaposition continue to show through. There is no beautiful, unified whole, no seamless blending of past and present, same and other, here and there; the world is merely frozen into an image of juxtaposition.

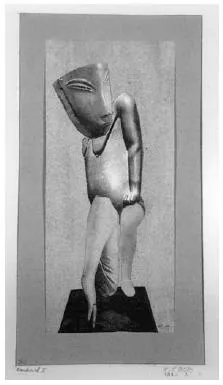

Working in this vein, from 1924 until 1934 Höch created a photomontage series that she called “From an Ethnographic Museum” in which she reimagines images of otherness in modern life, often juxtaposing the “primitive” and the “woman” as objects of a visual gaze. Among this series is the 1925 piece Denkmal I: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Monument I: From an Ethnographic Museum), which portrays a female figure fashioned from cutouts of magazines and wearing an African mask. She is a modern European woman and an African simultaneously (See Figure 1.1). The figure is placed on a platform (as with most of the pieces in the series), thereby stressing the objectifying way of seeing that is endemic to the modern, deritualized museum; “woman,” like the “primitive,” is put on a pedestal and offered as a commodified image to be consumed by, alternatively, the male, the Western ethnographer, and the museum viewer. Later commentators did not find Höch to be critical enough of the exoticizing tendencies of early ethnography in its approaches to African and Asian material culture, yet her point was to draw attention to the female body’s objectified status in Weimar Germany. Maud Lavin’s book-length study of Höch develops the artist’s sociopolitical interests via her aesthetic strategies:

Figure 1.1 Hannah Höch, Denkmal I: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Monument I: From an Ethnographic Museum), 1925. ©2004 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

What might be perceived as Höch’s humanistic linking of the subjecthood of Western and tribal peoples through montaging body parts (or often ethnographic artifact fragments representing body parts) is made ironic through her use of allegorical displacement. In structure as well as in tone, her exploration of self through a representation of the Other is explicitly ironic. Because of the fluid operations of reading a montage, however—the Blochian flowering of allegory—such a distanced irony is not a static or ever-present element of reception . . . . Oscillation is therefore important in Höch’s montages—prompting a disjunctive shift between one allegorical reading and another, allowing different types of identification and distance.3

Höch, like all artists, sets out to recreate the world, to defamiliarize and refamiliarize objects, allowing us to look again at our worldview, yet she does so in a way that does not create an image that is possessable, or with a fixed and final meaning.

Höch’s alternative title for this series was die Sammlung (the collection; a critical term for Benjamin to which I will return at many points), evoking the colonialist activity of “collecting” images and objects of the other. Colonization arises coterminously with the creation of modern museums of art and anthropology, both which arise alongside scientific observation and the scientific study of religion. The desire to collect, and therefore possess, is parallel to the desire to gaze and behold the other, and the impulse behind modern art and aesthetics is barely different from the masculinist, colonialist, scientific worldview: Modern science and modern aesthetics both view the other as distinct and autonomous, and only in this way can it be collected, possessed, and gazed upon by a self-reliant subject in a position of power. Höch’s ironic reappraisal of the colonialist situation disperses such collections, just as she offers up a collection that is made from fragments.

Inventing Religion

Through the allegorical fragment, Höch’s art, on one level, visualizes Benjamin’s aesthetic strategies, playing in the space between distance and proximity, between the part and the whole, as the images stress the pieced-together nature of social reality. She thus stands at the beginning of this chapter and book as a way into the field of Benjamin’s aesthetics. Furthermore, Höch’s art emblematizes the kind of creative activity that I will suggest Benjamin contributes to the study of religions.

Jonathan Z. Smith’s argument in his 1982 article, “In Comparison a Magic Dwells,” is that comparative religious studies have continued to retain a certain “magic” that sees too much resemblance among religious structures across cultures and thus tends to be unscientific. He ends up suggests an interesting distinction for comparing religions: “Borrowing Edmundo O’Gorman’s historiographic distinction between discovery as the finding of something one has set out to look for and invention as the subsequent realization of novelty one has not intended to find, we must label comparison an invention.”4 As already suggested in my introduction, invention is a rich creative notion that works beyond the intentions of the single creator and cannot maintain control over its subject. It is oriented toward a future that has not yet arrived and may never do so. Invention remains on the side of creativity, not objective science. In response to the objective, scientific endeavors of religious studies, a collection of essays on the topic was published entitled A Magic Still Dwells, in which editors Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray note the importance of Smith’s article, even as they acknowledge that there are revisions to be made: “We reclaim the term ‘magic’ to endorse and to extend his claim that comparison is an indeterminate scholarly procedure that is best undertaken as an intellectually creative enterprise, not as a science but as an art—an imaginative and critical act of mediation and redescription in the service of knowledge.”5

Relatedly, and not far from Benjamin’s own production as an author, Wendy Doniger suggests, “The comparatist, like the surrealist, selects pieces of objets trouvés; the comparatist is not a painter but a collagist, indeed a bricolagist (or a bricoleur), just like the mythmakers themselves.”6 Religious worlds are made up of borrowed fragments and pasted together in ever-new ways; myths are updated and transmediated, rituals reinvented, symbols morphed. Correlatively, to do religious studies one must become something of an artist, or as Daniel Gold puts it, “if part of what many writers on religion do is to communicate their visions of human truths, then they have something in common with artists.”7 Many artists, mythmakers, and religionists, however, often attempt to cover over the fact that their work is made up of borrowed fragments and instead they point to a seamless, wholly pure, and beautiful worldview. To the contrary, the aesthetics asserted herein do not allow the seams, the cuts, the fragments, the borrowings, to disappear. Religion is unfoundable, an impure activity full of sutures and pasted cutups. Benjamin’s religious aesthetics work in between the attraction of art and the distance of scientific objectivity, between fascination for the object and a critical detachment from it, between collecting and the collection (Sammlung): “the life of a collector manifests a dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order” (SW II, 487).

Aesthetic Apprehensions

[O]nce words come to dominate and occupy flesh and matter, which were previously innocent, all we have left is to dream of the paradisiacal times in which the body was free and could run and enjoy sensations at leisure. If a revolt is to come, it will have to come from the five senses!

Michel Serres8

To introduce Benjamin, religion, and aesthetics more fully, we must step back and rethink the definition of aesthetics itself. As my introduction notes, this book works from the etymological basis of aesthetics as sense perception, and it considers the ways in which materialist-oriented aesthetics might offer a new perspective from which to rethink religious studies. To rescue aesthetics via the senses, a few comments about the institutionalized field of study are necessary. Since most libraries’ stacks are already replete with histories of aesthetics—I briefly consider a few fragments of aesthetic history that are worth rethinking and will play out in relation to Benjamin’s writings.9

It is commonly understood that Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten founded the modern study of aesthetics in the mid-eighteenth century. Like all inventors, he did not “discover” something as yet unseen, but rather demarcated a particular section of the world, and gave it a name. Beginning with his dissertation in 1735 (published in English as Reflections on Poetry) and expanded upon in his 1750 Aesthetica (which remains untranslated into English), he cordoned off the field of sense perception and revived the Greek term aisthesis (sensory perception) as its name. Aesthetics was to be a new science dealing with the knowledge that is gained through the bodily senses. It would be a complement to the field of logic, the two together forming a more comprehensive theory of knowledge. Logic supplies us with “things known” (conceptual), while aesthetics supplies us with “things perceived” (perceptual). In Baumgarten’s initial positing of the field of aesthetics, there is no mention of “beauty.” And although it may seem a bold move in the realm of eighteenthcentury philosophy to include such corporeal interests, Baumgarten is nonetheless clear that aesthetics trucks with the “inferior faculty” of perception, while logic deals with the “superior faculty” of the rational mind.10 Following Baumgarten’s ultimate subduing of the sensual body to the rational mind, the sensual roots of aesthetics are largely forgotten today.

Baumgarten’s ideas led Terry Eagleton to state, “[a]esthetics is born as a discourse of the body.”11 Yet the discipline of aesthetics has been displaced into inquiries about style, art, beauty, and taste (i.e., the “taste” achieved by the mind not the tongue—even the terms used turn into disembodied metaphors). Baumgarten called these latter things aesthetica artificialis, as opposed to the sensually oriented aesthetica naturalis. So, whereas the “natural” scope of aesthetics is to examine the relation between “the material and the immaterial: between things and thoughts, sensations and ideas,”12 it has “artificially” involved itself in abstract theories about art and beauty. In their natural state,“The senses maintain an uncivilized and uncivilizable trace,” contends one of Benjamin’s most astute interpreters, Susan Buck-Morss, in ways that resonate with Serres and Eagleton, “a core of resistance to cultural domestication. This is because their immediate purpose is to serve instinctual needs—for warmth, nourishment, safety, sociability—in short, they remain a part of the biological apparatus, indispensable to the self-preservation of both the individual and the social group.”13 Such natural aesthetics are so close to our existence as Homo sapiens that we often overlook them, yet Buck Morss’s comments here suggest ways in which we might continue to tap into aesthetics as a powerful force for invention, for rethinking who we are as humans, and rethinking the status of religion.

Because its etymological roots and Baumgarten’s initial notions of it were materially based, philosophy’s pursuit of “truth” and theology’s pursuit of things “spiritual” have consistently had to push this corporeal, non- or prelinguistic category to the sidelines. Western philosophy and theology have pursued a truth that is transcendent and/or spiritual, and thus opposed to (or at least very skeptical of) the material. So in spite of some prominent philosophers attending to aesthetic matters, the field has fairly consistently been a marginalized subfield of philosophy, and even more of theology and religious studies. When not pushed to the sidelines, the study of aesthetics has developed ways to open material sensation to, as Eagleton puts it,“the colonization of reason;” aesthetics is “a kind of prosthesis to reason, extending a reified Enlightenment rationality into vital regions which are otherwise beyond its reach.”14 Reason, in its logocentric guise, guarantees borders and structures, promises unity, and puts the reasoner in control and possession.

In order for the mind to exert control over its objects of study, Western, dualistic modes of thought must maintain clear distinctions. Although mindbody dualism is a key contributing factor to the denigration of aesthetics, the most significant heritage is that which is at the heart of many religious traditions the world over: the interlinked dualities of the inside and outside, and the pure and impure.15 Because the bodily sense organs are physiologically situated at the cusp of the inside and the outside of the body—ears, nose, mouth, eyes, skin—the realm of aesthetics must be appropriated by the mind and retained “inside”—that is, subservient to the logic of reason—or is excised from the realm of thought and deemed unimportant for truth. Along with the anus and genitals, the five senses occupy a corporeal borderland, and this border is endlessly contested.16

Immanuel Kant is of course a key figure here, delineating various types of knowledge through his three critiques and attempting to account for knowledge that is separate from any experience. Yet as Buck-Morss sums up his relation to the senses: “Kant’s transcendental subject purges himself of the senses which endanger autonomy not only because they unavoidably entangle him in the world, but, specifically, because they make him passive (‘languid’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prescript: The Religious Uses of Benjamin

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations of Works Cited

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: Creative Aesthetics Creating Religion

- 1. Aesthetics (I): From the Body to the Mind and Back

- 2. Allegorical Aesthetics

- 3. Working Art: The Aesthetics of Technological Reproduction

- 4. Aesthetics (II): Building the Communal Sense

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index