eBook - ePub

Globalisation and the Asia-Pacific

Contested Territories

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Globalisation and the Asia-Pacific

Contested Territories

About this book

Most books that analyse the crucial subject of globalisation only look at it from a western perspective. This is the first detailed study to look at globalisation specifically in the Asia-Pacific region. An impressive collection of leading, interdisciplinary scholars explore various dimensions of globalisation and their relationship to development processes in the region.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Globalisation and the Asia-Pacific by Peter Dicken,Philip F. Kelly,Lily Kong,Kris Olds,Henry Wai-chung Yeung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Questions in a crisis

The contested meanings of globalisation in the Asia-Pacific

Introduction

A preoccupation with the ‘global’ has become one of the emblematic—almost obsessive—characteristics of our time. National political leaders, in particular, are increasingly adopting a global rhetoric to justify the economic (and often social) policy stance of their governments. Such rhetoric depicts globalisation as an unstoppable, unidirectional force that will inevitably transform economies and societies. Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong lucidly expressed this widespread sentiment in a speech to policy makers and analysts in Washington DC in May 1998:

Globalisation, fostered by free flow of information and rapid progress in technology, is a driving force that no country can turn back. It does impose market discipline on the participants, which can be harsh, but is the mechanism that drives progress and prosperity.

(Straits Times, 8 May 1998:67)

At the same time as politicians, journalists and analysts have joined the global bandwagon, virtually all of the social sciences have concurrently developed their own ‘take’ on the processes of globalisation. We now see an avalanche of books and articles on the subject. During the five-year period between 1980 and 1984, the Social Sciences Citation Index identified a mere 13 books or papers dealing with ‘globalisation’. In the five years from 1992–6, however, the number had grown to 581. In 1996 alone, the number of globalisation items reached 211. If we were to add all the other related works, the remarkable growth and recent acceleration in the quantity of the ‘global’ literature would be even more apparent. There are good reasons to be sceptical about such a bandwagon, but we believe that there is also a need to add to this debate.

The first reason essentially defines the purpose of this book. So much of the theoretical discourse on globalisation has emerged from Western contexts, and yet the processes, and the rhetoric, of globalisation have arguably worked with most transformative power in the Asia-Pacific region. But globalisation has not been uncontested, and across the region a series of contradictory tendencies are apparent in popular representations of globalisation: it has been ‘the’ route to economic triumph, but also the root of economic crisis; it has been resisted as an insidious process of undermining ‘Asian values’, but courted as a source of social change that produces cosmopolitan and reflexive citizens; and finally, it has been heralded as the end of the nation-state, and yet assiduously promoted by many states within the region.

In seeking to explore some of these contradictions in this volume we have not, however, sought to find an ‘Asian voice’ or ‘Asia-Pacific perspective’ on globalisation—the contributors currently work in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. Instead, each contributor explicitly considers the meanings and implications of globalisation for the Asia-Pacific region or some part of it. It is worth noting that in using the regional label of Asia-Pacific we have consciously chosen one of the more egregious regional constructions currently in circulation. As much as globalisation itself, the ‘Asia-Pacific’ is a contested territory (Dirlik 1993b; also see Higgott, this volume). There is, however, a certain utility in its vagueness. Perhaps more than any other world region, the boundaries of the Asia-Pacific are indeterminate and open to contestation and social construction. In using it to define the main geographical anchor of this book we therefore avoid the need to place definitive boundaries on the locus of our attention. To focus on ‘Southeast Asia’ or ‘East Asia’ would imply that globalisation represents an exogenous force impacting upon a definitive region. As we will discuss later, a key element in contemporary processes of globalisation is not the impact of ‘global’ processes upon another clearly defined scale, but instead the relativisation of scale. By focusing on the Asia-Pacific, the openness and fluidity of the regional construct is acknowledged and its linkages with other scales—the global, the state, the city, the firm, the personal, etc.—are more readily explicated. Thus each chapter, while taking globalisation as its starting point, also attempts to bring other scales of analysis into the picture. As a result, this is neither a book about the Asia-Pacific region per se, nor is it purely a decontextualised debate about the reality or merits of globalisation. Instead, it stands as a collection of diverse accounts of how globalisation is being experienced, understood, managed and resisted at various scales within the Asia-Pacific region. This ‘multi-scalar’ approach is also reflected in the structure of the book. The first part, ‘Global discourses’, addresses theoretical themes which take the global scale as their starting point, but explore its theoretical and political implications in various dimensions. In the second part, ‘Regional reformations’, sub-global regional spaces become the locus of analysis, but once again processes that transcend this fluid scale are examined in the context of the Asia-Pacific region. ‘Reterritorialising the state’ then considers the implications of globalisation for the scale of the nation-state, while the final part, ‘Global lives’, explores some of the implications of globalisation processes for social life and cultural identity.

Two other aims define the goals of this book. The first is to examine critically the concept of globalisation and its political, economic and cultural consequences. Unlike some of its predecessors on the intellectual catwalk of the social sciences—notably ‘postmodernism’—globalisation holds a great deal more purchase in policy circles and has been popularised in far more imaginative ways. This discourse of globalisation goes further than the simple description of contemporary social change; it also carries with it the power to shape material reality via the practical politics of policy formulation and implementation (Gibson-Graham 1996; Kayatekin and Ruccio 1998; Kelly 1999; Leyshon 1997). It can construct a view of geographical space that implies the deferral of political options to the global scale. In effect, globalisation ‘itself has become a political force, helping to create the institutional realities it purportedly merely describes’ (Piven 1995:8). Thus there is a peculiar reflexivity in the ways globalisation is represented and experienced. As Paul Hirst (1997:424) points out, globalisation is not just a fashionable idea, it is a concept with consequences. The contributions collected together here, then, do not simply describe, and certainly do not celebrate, globalisation; instead, they explore the complex meanings of the concept and the ways in which it might be rethought with greater rigour.

The final overall purpose of this book is to bring an interdisciplinary approach to bear upon the processes of globalisation in the Asia-Pacific region. While the literature on globalisation now consists of a number of distinct, though overlapping, approaches (economic, cultural, political, social), most of the academic debate still tends to occur within relatively sealed disciplinary compartments. Such compartments are becoming increasingly anachronistic as authors from ‘grey zones’ such as international political economy, economic geography and cultural studies draw intellectual stimulus from varied sources. An important purpose of this collection of essays, then, is to gather together multiple perspectives on globalisation from a wide range of scholars who are transcending their ‘traditional’ backgrounds in disciplines such as anthropology, economics, geography, history, planning, politics and sociology. In this way, the chapters reflect the diversity of processes that have become enmeshed in the broader idea of globalisation, including issues of cultural identity, cultural production, political institutions, manufacturing production, financial flows, migration and urbanisation.

The contributions gathered here were written during a period when debates over the meaning and consequences of globalisation in the Asia-Pacific were magnified by the economic crisis and social unrest spreading through East and Southeast Asia in 1997 and 1998. The ‘Asian financial crisis’, as it has come to be known, has fostered a heightened sense that globalisation implies the loss of control over the effective regulation of national economies and the diminished influence of societies over their own destinies. It has become much easier for actors in the Asia-Pacific region to imagine the direct and indirect ‘discipline’ that can be imposed by ‘global’ financial markets, multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global superpowers (the US) and private entities such as international credit ratings agencies (Moody’s or Standard and Poor’s).

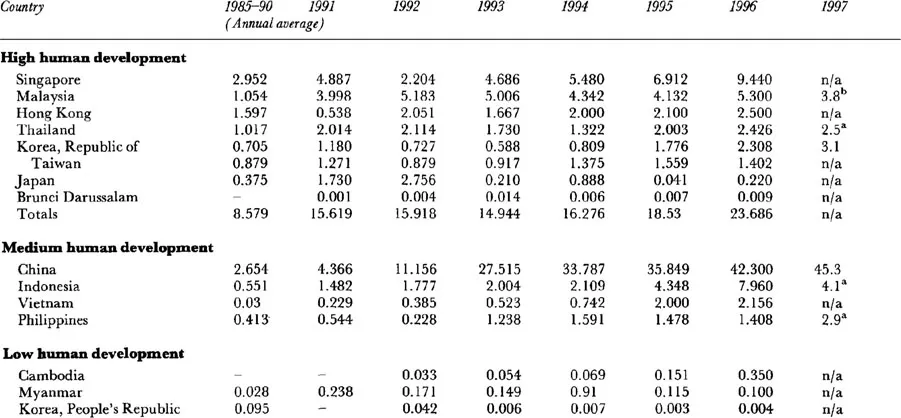

Table 1.1

FDI inflows to East and Southeast Asia, by host economy, 1985–97 (billions of dollars)

FDI inflows to East and Southeast Asia, by host economy, 1985–97 (billions of dollars)

Source: Compiled from UNCTAD (1997) and International Chamber of Commerce and UNCTAD (1998) <http://www.unicc.org/unctad/en/pressref/bg9802en.htm>, accessed 13 May 1998.

Notes:

a Estimates.

a Estimates.

b Not including reinvested earnings.

While the issues that are examined in this book have been brought to the fore during the economic crisis of 1997–8, recent events do not represent the beginning (and certainly not the end) of the discussion over globalisation in the region. Rather, the crisis simply provides a starting point for more ‘fundamental’ debates about globalisation in the Asia-Pacific. Discussions on the underlying causes and potential solutions to the Asian economic crisis have heightened awareness of several key themes that will be explored in greater theoretical and empirical depth in this volume. In the next section of this introductory chapter, then, we will provide a brief outline of the experiences of globalisation that the 1997–8 crisis precipitated. Subsequently, we broaden the discussion to highlight some of the wider issues and enduring themes relating to globalisation in the Asia-Pacific that have emerged from the crisis and which weave their way through the chapters in this book.

National crises, regional crisis, global crisis

An account of the financial crisis of 1997–8 inevitably reads as a rather economistic interpretation of what globalisation means. The papers in this collection, as we have already pointed out, take a much broader view of globalisation, but as we will argue, the questions which emerge from the financial crisis go far beyond the confines of economic processes and policy. As a starting point, however, the story of the Asian economic crisis runs something like this.

Southeast Asian growth (especially in Malaysia and Thailand, latterly in Indonesia and the Philippines) has been fuelled by inflows of foreign direct investment from other Asian economies, notably Japan and the ‘Asian NICs’—Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong. While the flows of investment grew throughout the 1980s, they accelerated considerably in the 1990s, especially in countries such as Indonesia (see Table 1.1).

The impetus for this transborder flow of investment was the decreasing global competitiveness of companies in source countries, their need to relocate to lower cost locations, and their efforts to gain footholds in emerging markets (UNCTAD 1997). Southeast Asian nations responded with liberalised financial sectors, industrial location incentives, high domestic interest rates (to attract portfolio investment), and a dollar peg to insure investors against currency devaluation (Bello 1997a; UNCTAD 1997:79–85). In addition, the 1990s saw a rapid expansion of foreign portfolio equity investment and private lending in the Asian region (UNCTAD 1997:112). Attracted by the ‘dynamism’ of these economies, net capital inflows (long-term debt, foreign direct investment, and equity purchases) to the Asia Pacific region increased from US$25 billion in 1990 to over US$110 billion in 1996 (Greenspan 1997). This created what Walden Bello (1997b) calls ‘fast-track capitalism’, with rapid industrialisation and ballooning capital markets.

Much of the inflowing capital did not, however, find its way into productive agricultural or industrial sectors, but instead gravitated towards the stock market, consumer financing and real estate. These sectors boomed, while commodity and manufactured exports, the mainstays of national economies in Southeast Asia, became less competitive in the global market place. Domestic financial sectors were making capital liberally available, but regulation of lending standards was lax and many institutions were making loans on the basis of already inflated assets in a circular process that led to further appreciation. While this virtuous circle continued to inflate, financial institutions were borrowing in US dollars and lending in local currency (Radelet and Sachs 1998). But since 1995 the dollar had been appreciating against world currencies—gaining 50 per cent against the Yen between 1995 and 1997 and Southeast Asian currencies were going up with it.

The circle was broken in July 1997. The proximate causes may have been a global slowdown in the semiconductor industry in 1996, a strengthening dollar, low wage competition and currency devaluation in China, or rising wage costs in Asia—all of which caused exports to stagnate in 1996 and 1997 (Corsetti et al. 1998; Radelet and Sachs 1998; Wade and Veneroso 1998a). Thus while Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and China all maintained positive current account balances in 1996, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, Malaysia and Thailand saw deficits of between 4 and 8 per cent of GDP (The Economist, 7 March 1998). But whatever the stimulus for panic, when global financial managers detected a disparity between exchange rates and global competitiveness, institutional investors and speculators began to move capital out. The Thai government of Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, having given repeated assurances that it would resolutely defend the currency against any speculative attack, finally conceded defeat after spending over US$9 billion of the country’s foreign currency reserves. On 2 July 1997, the Thai baht was allowed to float against the US dollar and immediately lost 15–20 per cent of its market value.

Other Southeast Asian economies were based on similar but not identical foundations—including broadly pegged exchange rates, banks with overexposure in the property sector, huge unhedged short-term foreign loans, a lack of ‘transparency’ and regulation in the financial sector, and sluggish export receipts—and their currencies came under similar pressures. A financial contagion spread across the region, fuelled to some extent by fears of declining competitiveness against economies with already devalued currencies and similar problems in financial regulation, but also by less rational sentiments of self-fulfilling panic concerning the movement of the market. The situation was also exacerbated by domestic investors quickly seeking to hedge their foreign currency exposure by buying dollars. By mid-October, the Indonesian and Thai currencies had lost over 30 per cent of their value against the dollar since July, and the Malaysian ringgit and Philippine peso more than 20 per cent (IMF 1998).

By November 1997 the crisis had spread to South Korea where investors detected a similarly problematic set of debt structures among industrial conglomerates. In particular, the politically motivated nature of some lending and the massive short-term foreign debt provided cause for concern (in June 1997 South Korean short-term foreign debt amounted to more than three times the country’s foreign exchange reserves, and by December 1997 it was fourteen times (The Economist, 7 March 1998; Wade and Veneroso 1998a).

As the months passed, side-shows to the main drama unfolded and fanned market sentiment against the region. In August and September 1997, Prime Minister Mahathir of Malaysia engaged in a public debate with New York investment banker George Soros (among others) over the morality and merits of currency trading and speculative investment. With each new salvo, currency and stock markets dipped still lower. Meanwhile in Indonesia, political pressure on President Suharto mounted as he played a cat-and-mouse game with the IMF, which was applying pressure for economic and political reforms.

By the end of 1997, Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea had signed bailout packages with the IMF in an attempt to resuscitate ailing capital markets that were no longer capable of repaying bloated dollar loans to foreign banks, or servicing the needs of productive local enterprises. In the first quarter of 1998, Indonesian exporters were in dire straits as foreign banks refused to accept letters of credit from Indonesian institutions, even when guaranteed by the national government. Thus export manufacturers were unable to import raw materials. The IMF’s strategies of insisting on increased fiscal surpluses in countries where budgets where already in surplus and cloaking its negotiations in secrecy while demanding transparency from recipients, led to criticism of the institution from various quarters.

In Indonesia, and to a lesser extent Thailand, the financial turmoil cum economic crisis also turned into a political crisis. IMF conditions became the key to ‘market confidence’, but these conditions conflicted with embedded political-economic power structures and vested interests. Growing hardship and latent dissatisfaction erupted into outright hostility in urban areas across Indonesia and among many middle-class urbanites in Bangkok. In Thailand, a new government was installed in November 1997, but in Indonesia social unrest continued after Suharto’s ‘re-election’ in March 1998 to a seventh five-year term in office. Anger was directed against the Suharto regime itself, and against ethnic Chinese Indonesians who have frequently borne the brunt of ‘pribumi’ (ethnic Malay) frustrations. This social unrest translated into increasing flows of illegal immigrants from Indonesia, causing fears in Singapore and Malaysia of a massive influx if conditions worsened. Finally, as tensions mounted and unrest intensified on the streets of Jakarta and other cities, Suharto announced his imminent resignation on 19 May and then his immediate replacement by B.J. Habibie on 21 May. Whilst the links between the volatile nature of the global financial system and such violent political turmoil may not be direct, they surely cannot be denied. As Krist of noted in the International Herald Tribune:

when Mr. Suharto pledged in a sober television address to the nation on Tuesday [19 May] that he would step down from office, the force that had led to this stage was not a Communist insurgency but a conspiracy of far more potent subversives: capitalism, markets and globalisation. Instead of hiding in the jungle, they established a fifth column in glass-and-steel towers in the major cities, and Mr. Suharto’s security forces never figured out how to handcuff or torture them into submission… His sophisticated military equipment can detect a guerilla in the jungle of East Timor at night, but it was unable to discern bad bank loans or prop up a tumbling currency.

(Kristof 20 May 1998)

Interpreting the crisis

This simple sketch of the financial crisis leaves plenty that is open to interpretation and debate. Some commentators noted that poor investment decisions by financial intermediaries in Asia were being punished, but the sources of that capital (predominantly Western banks) were enjoying the full attention of the IMF to ensure that their loans were repaid. Others raised the possibility that the discipline and surveillance of the IMF in the region represented little more than a thinly veiled attempt by American/Western capital to crack the protectionist and monopolistic shell still enveloping many economies (Lim et al. 1998). Under this interpretation, the crisis represents not just a vulnerability to globalised capital flows, but also an attempt to globalise certain financial practices and systems of economic regulation—hence the imposition of a particular ‘brand’ of capitalism. In general, however, interpretations of the crisis seem to fall within four distinct categories.

The first focuses on the ‘crony capitalism’ and market interference that supposedly suffuse...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Routledge/Warwick Studies in Globalisation Series preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Questions in a crisis: The contested meanings of globalisation in the Asia-Pacific

- PART 1. Global discourses

- PART 2. Regional reformations

- PART 3. Reterritorialising the state

- PART 4. Global lives

- References

- Name index

- Subject index