- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Open and Distance Learning in the Developing World

About this book

This revised and updated edition of Open and Distance Learning in the Developing World sets the expansion of distance education in the context of general educational change and explores its use for basic and non-formal education, schooling, teacher training and higher education.

Engaging with a range of topics, this comprehensive overview includes new material on:

- non-formal education: mass-communication approaches to education about HIV/AIDS and recent literacy work in India, South Africa, and Zambia

- schooling: new research projects in open schooling in Asia and subsaharan Africa, and interactive radio instruction in South Africa

- the impact of new technology and globalisation: learning delivered through the internet and mobile learning

- the political economy: international agencies, the role of private sector, and funding.

With its critical appraisal of the facts and examination of data about effectiveness, this book provides answers to problems and poses key questions for the consideration of policy makers, educational practitioners and all professionals involved in implementing and delivering sustainable open and distance learning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ÉducationSubtopic

Éducation générale1 Introduction: golden goose or ugly duckling

There is the familiar circle to be squared: a poor country cannot afford health and education, but without them it cannot even develop such economic resources as it has.

W. M. Macmillan 19381

Distance education began in 1963. In that year Michael Young and Brian Jackson were establishing the National Extension College as a pilot for an open university; Harold Wilson, soon to become prime minister, was calling for one; UNESCO was planning to use distance education to train refugee Palestinian teachers, and the Ecole Normale Supérieure at St Cloud was beginning to experiment with what came to be called educational technology. The Robbins report on higher education noticed with approval and surprise that the Soviet Union was using correspondence education. A global flurry of activity has followed. The Open University was established in Britain to be followed by over forty more across four continents. Radio campaigns were used for public education in Africa, and open schools set up in Asia. Today, between 5 and 15 per cent of university students in industrialised countries are likely to be studying at a distance; in developing countries the figure is often between 10 and 20 per cent. The pace at which this has happened, and the scale it has now reached, make open and distance learning worth critical analysis. This book attempts that analysis, asking how well open and distance learning responded to the educational needs of the south in the late twentieth century and what are its achievements and prospects, in the twenty-first.

Open and distance learning has grown because of its perceived advantages.

First is its economy: school buildings are not required and teachers and administrators can be responsible for many times more students than they can accommodate in a school. Its second main advantage is its flexibility: people who have got jobs can study in their own time, in their own homes, without being removed from their work for long periods. Its third advantage is its seven-league boots: it can operate over long distances and cater for widely scattered student bodies.

(Dodds et al. 1972: 10)

Responding to this kind of argument, educators in industrialised, developing and transition countries have used open and distance learning to help solve their problems of resources, access, quality and quantity: running education with too little money; opening doors to new groups of students; raising the quality and standard of education; expanding numbers.

Expansion and constraint

Open and distance learning has grown within a more general expansion of education. The world's schools, colleges and universities have grown more rapidly in the last half century than ever before. In 1960, as the European empires were fading away, only one child in four got to school in subsaharan Africa, one in two in Asia, and only just over one in two in Latin America. Today, though millions are still outside school, most children, throughout the world, at least begin at primary school. Some countries of the south are now sending to school and college nearly as many of their children and young people as the industrialised countries of the north; others have reached the levels that were the norm in OECD countries in the 1960s (UNESCO 1993: 30–1). And this huge improvement has been achieved alongside other dramatic social advances. The world has managed to get to 80 per cent immunisation of children and, just in the 1980s, to increase the ‘proportion of families with access to safe drinking water from 38 to 66 per cent in South-East Asia, from 66 to 79 per cent in Latin America, and from 32 to 45 per cent in Africa’ (Bellamy 1996: 62). Although it has been uneven, and inadequate, there has been progress, in an old-fashioned nineteenth-century sense, which can be measured in terms of the numbers of children and young people in school or college (table 1.1). We can acclaim that progress, noticing the colossal human achievement in filling the educational cup even half-full. But of course it is not the whole story.

The process of educational expansion has been neither smooth nor simple. There was a ‘quantitative mismatch between the social demand for education and the means for meeting it’ as the developing countries of the world faced an unprecedented set of demands (Coombs 1985: 34). They needed to expand education, in response both to political pressure and to the growing economic and social evidence of its benefits. They were doing so with dependency ratios much less favourable than those that had applied as industrialised countries moved to universal education. (When Britain attained universal primary education in 1880, 36 per cent of the population were below the age of 15; the figure had fallen to 22 per cent when Britain reached universal secondary education in 1947. The comparable figures for subsaharan Africa and south Asia in 1970 were 44 and 45 per cent.) And they were doing so at a time when rapid population growth meant that educational systems needed to run in order to stay still. Literacy figures illustrate the conundrum; while the proportion of illiterate people in the world has been falling since the 1960s, it was only some time in the 1980s that the actual number began to drop, to a figure of around 860 million; in three regions of the world – south and west Asia, subsaharan Africa and the Arab states and north Africa – numbers continued to rise through the 1990s (UNESCO 2002a: 61–2).

Table 1.1 World educational expansion

| (figures in millions) | ||||

| 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | |

| Total student numbers | ||||

| Developing countries total | 404.4 | 625.5 | 742.6 | 967.2 |

| Primary | 312.8 | 449.2 | 505.9 | 570.4 |

| Secondary | 84.8 | 159.4 | 207.9 | 358.8 |

| Tertiary | 7.0 | 16.9 | 28.8 | 38.0 |

| Countries in transition total | 78.6 | 58.3 | ||

| Primary | 29.7 | 15.0 | ||

| Secondary | 38.2 | 31.3 | ||

| Tertiary | 10.7 | 12.0 | ||

| Industrialised countries total | 204.1 | 231.5 | 159.3 | 196.1 |

| Primary | 98.6 | 92.4 | 61.3 | 69.5 |

| Secondary | 84.5 | 105.0 | 68.9 | 89.6 |

| Tertiary | 21.1 | 34.2 | 29.1 | 37.0 |

| Gross enrolment ratio | ||||

| Developing countries ratio | ||||

| Primary | 81.2 | 94.9 | 98.9 | 101 |

| Secondary | 22.7 | 35.3 | 42.1 | 55 |

| Tertiary | 2.9 | 5.2 | 7.1 | 13 |

| Countries in transition ratio | ||||

| Primary | 96.5 | 105 | ||

| Secondary | 91.6 | 90 | ||

| Tertiary | 36.1 | 49 | ||

| Industrialised countries ratio | ||||

| Primary | 99.2 | 100.9 | 102.8 | 102 |

| Secondary | 75.7 | 89.4 | 94.5 | 105 |

| Tertiary | 26.1 | 36.2 | 48.0 | 56 |

Source:UNESCO Statistical Yearbook 1999 (I970–80); UNESCO 2000 (1990) UNESCO 2005 (2000, using figures for 2000/1).2

Ministries of education needed to resolve another paradox as they built more schools and enrolled more children. The shortage of qualified labour for the modern economy, and the need to localise employment in the highly visible public sector, together made the case for expanding secondary and tertiary education a priority. This view fitted with that of the major funding agencies. From its very first loans for education in the 1960s, the World Bank was prepared to lend for secondary and vocational education (Jones 1992: 75) and in practice, over many years, has also funded higher education (ibid: 208). Expansion at these levels also responded to powerful political demands: the children of the urban elites, of those who were making the key educational decisions, were the ones who would suffer if investment in secondary and tertiary education was held back at the expense of primary schools, and especially of rural primary schools. The cost per student at these levels was higher, in some cases dramatically so, than the costs of primary education. At the most extreme, putting one child into university kept sixty out of primary school.3 And yet the social, political and economic case for expanding primary education remained unassailable.

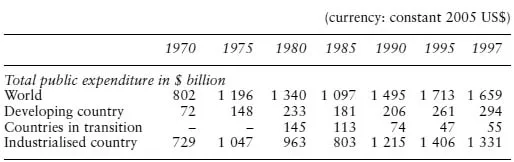

A series of checks have also constrained the expansion of schooling. In the 1970s one ‘was the OPEC oil shock, which sent prices soaring and ended the era of cheap energy and cheap industrialization – and therefore of cheap development. The other was the global food shortage brought about by two disastrous world harvests in 1972 and 1974’ (Bellamy 1996: 55). Developing countries found that they could not expand education at the same pace in the 1970s as in the 1960s. Worse was to come. Falling prices for primary products marked the downturn in world economies in the 1980s. Many countries were forced to turn to the World Bank and IMF who negotiated or imposed policies of structural adjustment designed to transform longterm economic prospects. One element of structural adjustment, which fitted well with the views of the new right, was to hold back government expenditure, on education as in other sectors. Public expenditure on education in developing countries, set out in table 1.2, fell from $230 billion in 1980 to $180 billion in 1985 (in constant 2005 currency);4 expenditure per inhabitant fell by 30 per cent from $73 to $50.

The effect was at its most severe in subsaharan Africa. Africa's total debt, as a proportion of GNP, soared between 1980 and 1995, so that it surpassed its GNP (ibid.); increases in Asia were more modest while indebtedness in Latin America and the Caribbean declined from the early 1980s. Less money meant fewer children in school. In fourteen countries, a smaller proportion of primary-age children were going to school in 1992 than in 1980 (UNESCO 1995: 130–1). Sadly, a decade later, UNESCO reported that ‘net enrolments appear to have either faltered or scarcely increased during the 1990s’ (UNESCO 2002a: 47).

Table 1.2 Estimated world total public expenditure on education 1970–97

Source: UNESCO Statistical Yearbook 1986 (1970–75); UNESCO 2000(1980–97).

While educational progress has been faltering, at least in some parts of the south, it has done so under a new international spotlight. Two world conferences on Education for All, at Jomtien in Thailand in 1990 and Dakar in Senegal in 2000 drew world attention, and in particular the attention of the international funding agencies, to the needs of basic education. At Dakar the world's representatives pledged themselves to achieving gender parity in basic education by 2005 and basic education for all by 2015. During the course of the Dakar conference targets for adult education were added to those for children. The effects of the conferences are more difficult to assess. By 1995 it was clear that the targets agreed in Jomtien would not be achieved although basic education was ‘now firmly established as a central objective of education aid by virtually all donors’ (Bennell 1997: 27). By 2005 it was clear that the gender target would not be met. While entry to primary school has risen, the 2015 target still looks improbable, especially in south Asia and subsaharan Africa: large numbers of children, more of them girls than boys, remain outside school.

The shortage of resources has not ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of tables

- Foreword by Lord Briggs

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: golden goose or ugly duckling

- Part 1 Evidence

- Part 2 Explanation

- Part 3 Evaluation

- Annex Currency values

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Open and Distance Learning in the Developing World by Hilary Perraton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Éducation & Éducation générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.