- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume brings together for the first time critical work by Pinays of different generations and varying political and personal perspectives to chart the history of the Filipina experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pinay Power by Melinda L. de Jesús in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VI

Peminist Cultural

Production

18

Sino Ka? Ano Ka?: Contemporary Art by Eight Filipina American Artists

VICTORIA ALBA

Over the course of the century that began shortly after the declaration of Philippine independence in 1898, Filipino Americans—initially a negligible portion of the immigrants coming to the United States—emerged as the country's fastest-growing Asian American minority. Today, more than 250,000 Filipino Americans live in the San Francisco Bay Area; more than two million live in the entire country.

Despite these large numbers, Filipino Americans as a group have yet to be sufficiently recognized as part of America's artistic mainstream. It is within this context that Sino Ka? Ano Ka?, a group exhibition of Filipina American women artists, unfolds. While preparing for this essay, I was asked by a friend and former colleague—an artist himself—why such an exhibition was even worth undertaking. I was stunned because during the four years we had worked together at a local museum he had not only expressed pride in his own Jewish heritage but had also been interested in African American and Chicano art and the art of other ethnic Americans. At his request, I recited the names of the featured artists, of which he recognized only one, to which he responded, “How is her work Filipino?” This utterance makes clear the need for an exhibition such as Sino Ka? Ano Ka?—which fittingly translates as “Who are we? What are we?”

Well, we are everything and everywhere: young, old, poor, rich, straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, neighbors, friends, artists, nurses, doctors, students, teachers, secretaries, managers, entertainers, software engineers, war veterans, newspaper vendors, and more. Statistically, we are one out of every twenty-five people in the San Francisco Bay Area. At times, it is not even apparent who we are: we can be light or dark, short or tall; we can be mistaken for Mexican, Indian, Indonesian, Malaysian, Samoan, Hawaiian, Japanese, Chinese, or European; what does a Filipino look like, anyway? My point is that Filipino Americans are a diverse group, little understood by the general public.

It is diversity, not homogeneity, that distinguishes Sino Ka? Ano Ka? Its participants have at least five things in common: they live in the Bay Area; have ties to Filipino culture, either through family or upbringing; are all women; are professional visual artists; and, above all, have chosen to exhibit their works alongside those of other Filipina American women (in the past, this might have been referred to as “solidarity”). Beyond this it would be difficult to make sweeping, across-the-board judgments about them or their art. The artists are from different backgrounds and have had unique experiences, each one the product and participant of a certain time and place; their works reflect a particular zeitgeist (spirit of the time) and weltanschauung (worldview). Their ages range from twenty-four to forty-five. Three were born in the Philippines, five in the United States. Two of the women are of mixed racial heritage, while one of the women is self-described as “white.”

It shouldn't surprise anyone that no two of the artists are alike. However, there are many that, when confronted with identity-based shows, assume this will be so. Furthermore, there are people like my friend who expect all the works to “look” Filipino.

The contemporary expressions featured here vary in content, media, and approach. Some of the artists operate collectively, others always alone. A few stick to one medium; most work in several media, among these, textiles, video, performance, and installation. Some have political agendas and engage in social protest and/or public art projects. Gender issues, feminist concerns, and Filipino American identity might be overtly addressed, submerged, or omitted. A lot of the artists inject humor into their work. Nearly all ask intelligent, challenging questions of their audiences.

Before discussing the individual artists and their work, I offer the words of twenty-nine-year-old artist Reanne Estrada, who notes, “I'm glad this exhibition is taking place. Hopefully, when people see the show they'll become aware of the variety of the work that's being done by artists who happen to be women and happen to be of Filipino origin. Because a lot of times the hardest thing about being a Filipina artist is that people want to pigeonhole you, they automatically assume that your work has to be overtly about your identity. No one necessarily expects this of a white male.”

Terry Acebo Davis (b. 1953, Oakland, California)

Terry Acebo Davis says, “Our history as Filipino Americans exists as more of an oral history—we learn it through the stories of our parents, uncles, aunts, and fellow kababayan [countrymen]. As an artist, I believe it is my duty to pass these stories on through visual language.”

For years, Acebo Davis has simultaneously balanced the careers of nurse, visual artist, arts educator, and activist. It is her artwork, however, that most passionately reflects her ethnic background. Her installations and works on paper continually evoke Filipino and Filipino American history and culture.

They are personal and political: sources range from her family's oral histories and photographic albums to materials gleaned from public archives and books.

Whether figurative or abstract, her works always allude to narrative. Her installations incorporate prints, manipulated photographs, and audio recordings, as well as actual objects invested with symbolic meaning such as field crates, thongs cast in bronze, and banig, woven sleep mats. Her prints are generally abstract and draw upon an array of printmaking processes and collage to call attention to form, color, and line. Text is as important as iconography, and letters and numbers are treated as discrete design elements. The surfaces to be printed on are equally critical: a Filipino theme might be paired with Philippine handmade paper fabricated from cogon, a native grass.

Many of her works address women's issues. And her reverence for art history is reflected in visual references to such trailblazers as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. Meanwhile, her interests in medicine and art converge in numerous pieces depicting the body and its parts—anatomical references that at times enlist the tools of twentieth-century technology. A foot might appear as a drawing, photograph, or x-ray.

The haunting 73 (1997), a crosslike formation of screen prints rendered in black on brown, is based on a CAT SCAN (brain X-ray or computerized axial tomography) of her father's brain after a stroke at age seventy-three. The damaged brain tissue, roughly the size of a grapefruit, registers as hollow blank space. Acebo Davis conveys her sense of loss by filling the void with a photograph of her father in his youth.

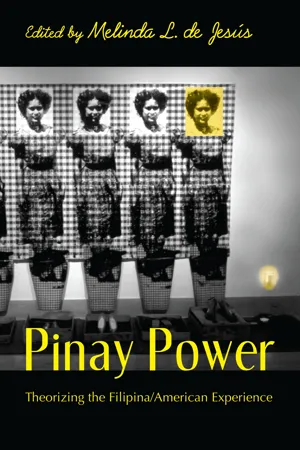

The materials of Dahil Sa Iyo (Because of You; 1995) are domestic in origin: checkered plastic tablecloth and placemats, a wooden serving set, a night-light, and crates with shoes. These are combined with life-size multiple screen prints of her mother to pay homage to the Filipinas of her mother's generation, immigrant women who held together their families and looked after the home. The reiterated figure is totemic, serving to emphasize the importance of the artist's female lineage.

Acebo Davis was born in Oakland and moved with her family to Fremont in the early 1960s. She received her first bachelor's degree in nursing from California State University-Hayward in 1976, then pursued a graduate degree in pediatric oncology at the University of California-San Francisco in 1985; she received a B.F.A. in printmaking from San Jose State University in 1991 and an M.F.A. in pictorial arts from San Jose State University in 1993. In 1997, she was the recipient of the James T.Phelan Award for Printmaking. Acebo Davis collaborates on installations and performances with the Filipino American artists collective DIWA (the word diwa is Tagalog for “spirit”).

Eliza O.Barrios (b. 1968, San Diego, California)

A filmmaker, videographer, and installation artist, Eliza Barrios is clear about the consistent underlying theme of her personal art: “The work I deal with has

Fig. 18.1 Terry Acebo Davis. Dahil Sa lyo, 1995. An installation: screened imagery on mixed media (66″×84″×18″). (Reprinted with permission of the artist.)

much to do with systems and processes, primarily how internal belief systems relate to external belief systems and how my Filipina heritage plays into this.”

Although she was raised in San Diego, Barrios's upbringing was governed by the traditional values of her Philippine-born parents. She embraced many of these principles as her own but from an early age began questioning their expectations of her gender. Barrios remembers, “My parents raised my sister and I to be good Filipina girls and my sister picked up on that—she did hula and piano lessons, and slumber parties, whereas I wanted to be the boy, to play outside and do everything else. I was in my own world. I knew these feminine ideals and expectations were there, but I also knew I didn't want them. I wanted more freedom to be unconventional.”

At sixteen, Barrios learned to express herself through photography, discovering a world of her own making. She continued to study photography through college and eventually moved beyond the two-dimensional plane by incorporating found objects and other sculptural elements. She also developed her content; in time, her art became a means for articulating her views concerning power and authority, society versus individual choice.

Barrios seized upon nails and hands as recurring motifs. She notes, “The hands can say as much about a person as the face. In the way they gesture, hold, clench, they can supply so many leads, yet at the same time, unlike a face, they're anonymous.” Hands are a central metaphor in her elegantly minimalist piece Solemn (1996).

Solemn consists of eleven bare lightbulbs dangling on electrical cords suspended from above. Each bulb is positioned over a large steel funnel resting on a stand. At the base of the stand is a bowl containing water. In the bowl, visible at close range, is a projected image of a pair of hands. Moving from left to right, the hands, which are at first clasped together, open sequentially until they finally part. In this commentary on the dissemination or “funneling” of information and knowledge, the hands signify the human recipient, master of one's fate or passive object of control. With its austere symmetry, formal severity, and sleekness devoid of color, Solemn initially strikes the viewer as coldly industrial. Only as one approaches—that is, interacts with the work—can one discern its ultimately intimate message.

Solemn is deceptively neat, leading the viewer to believe that it was effortless to construct. In fact, it took Barrios two years to research and build the piece. While it meets her rigid standards—an admirer of Bauhaus and Japanese architecture, Barrios always strives for a clean, sharp look—its design is also practical. The highly symbolic funnels, for instance, are capacious enough to house slide projection mechanisms.

Barrios received her B.A. in photography and art in 1993 from San Francisco State University and her M.F.A. in 1995 from Mills College. Her installations have been shown extensively in Hawaii and California and her films screened at festivals internationally. Barrios has collaborated with DIWA

Fig. 18.2 Eliza 0.Barrios. Solemn (detail), 1996. Metal funnel, tungsten light, ceramic bowl, photo negative plate, wood shelving (48″×12″×36″). (Reprinted with permission of the artist.)

and, along with Reanne Estrada and Jenifer Wofford, is one of the three members of Mail Order Brides.

Reanne Agustin Estrada (b. 1969, Manila, Philippines)

Perhaps none of the artists in Sino Ka? Ano Ka? are as engrossed with the artistic process as Reanne Estrada. Four years ago, Carlos Villa invited Estrada to create a “quilt of dreams” for an installation in conjunction with the Filipino Arts Expo at Center for the Arts. It would cover a bed in a room typical to one that might have been found at the International Hotel. A cultural fixture, the Kearny Street building constituted the heart of an area once known as Manilatown. During the first half of the twentieth century, the hotel was often the first stop for newly arrived Filipino immigrants. As its clientele aged, the hotel became an affordable, if modest, home for Filipino and Chinese seniors.1

Estrada was given free reign in terms of design, material, and mode of manufacture. Having little money but lots of time, she got her hands on some free fiber-optic cables, which she proceeded to gut. She untwisted the wires within, sorted them by color, and rolled them up like big balls of yarn. Then, by hand, she crocheted her bedspread: adjoined colored wires fashioned into hundreds of phrases that poignantly recalled the life of a manong, a Filipino old timer.

Although her current projects are much smaller in scale, they are almost as frugally produced and laboriously formed. Most recently, Estrada has been working with hair and Ivory Soap, which, in her capable hands, can remarkably resemble its namesake. Her carved pieces are reminiscent of antique Japanese netsuke sculpture. However, while these decorative miniatures imitate ancient Japanese or Chinese objéts d'art, they are contemporary in function (e.g., a contact lens case, a dental floss holder).

Sometimes Estrada leaves the soap intact and laces its surface with strands of hair collected from her brush and shower. The result is not unlike scrim-shaw, as the bars look as if they have been finely etched. In an environment as dust-free as possible, Estrada has created complex patterns and designs, such as chevron stripes, labyrinths, and a Philippine flag. These “soap drawings” can take weeks to complete.

Estrada adds a final flourish of tongue-in-cheek by exhibiting the “soap drawings” in museum cases lined with black terry cloth, whi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Toward a Peminist Theory, or Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience

- I Identity and Decolonization

- II (Re)Writing Peminist Sociohistory

- III Peminist (Dis)Engagements with Feminism

- IV Theorizing Desire: Sexuality, Community, and Activism

- V Talking Back: Peminist Interventions in Cyberspace and the Academy

- VI Peminist Cultural Production

- Contributors

- Permissions

- Index